LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: The friction between religion and science began long ago. Galileo, one of the fathers of modern science and a Catholic, was condemned by the Church and put under lifetime house arrest in part because he championed the controversial theory that the solar system revolves around the sun and not the earth.

DR. JENNIFER WISEMAN (Director, AAAS Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion Program): I think what his real problem was that he came across as though he was challenging Church authority, and they didn’t like that.

SEVERSON: Jennifer Wiseman is the director of Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the world’s largest scientific society. She oversees a new program called Science for Seminaries.

WISEMAN: And it turns out that many people actually look to their religious leaders for guidance on all kinds of things, but things including issues related to science and technology. And a lot of those religious leaders have had very little exposure to science in their training.

SEVERSON: The society asked seminaries to apply for grants that would enable them to incorporate more science into religious studies. They were surprised when 28 applied. Ten were accepted, including Multnomah University in Portland, Oregon, a private, nondenominational Christian school.

This is Professor Paul Louis Metzger, director of the seminary’s Institute for the Theology of Culture.

PROFESSOR PAUL LOUIS METZGER (Professor of Christian Theology and Theology of Culture, Multnomah University): So many young Christians are concerned that they don’t feel that their churches are really engaging them in terms of their passions, their vocational passions. And so if they’re training for the sciences and the churches themselves are not helping to equip them, there’s a sense in which they’re going to be lost.

SEVERSON: Over 250 seminaries were invited to apply. Only about 10 percent did. Some schools felt their students had already been exposed to science, and some thought the AAAS had a materialistic, scientific worldview—something they were opposed to.

METZGER: There will be pushback from a variety of domains, from a variety of individuals, communities. We might not always agree, but how can we at least seek to move forward toward a civil dialogue? And that’s something I’m hoping that we’ll be able to promote through this grant at the seminary.

SEVERSON: Science for Seminaries is just getting underway. Some schools don’t start the program until next semester. But at this class at Multnomah they are already asking the big questions. This is Katrina Johnson:

KATRINA JOHNSON: Well, it’s interesting that some neuroscientists say that there’s a center of the brain they’ve located that becomes activated when people engage in these, and they call it “the God center.”

SEVERSON: This is Derick Peterson, a divinity master’s student:

DERICK PETERSON: I think there’s a lot of mythology that gets traded around on all sides about what we believe, about what scientists believe. There’s a lot of parsing that needs to go on, a lot of education just to kind of say look, there’s not all these monsters hiding in the shadows, things that we don’t know.

SEVERSON: A survey by the American Association for the Advancement of Science found that almost a third of Evangelicals see a conflict between religion and science, and side with religion. Another poll by the Associated Press suggested that half of Americans, including 77 percent of evangelicals, are skeptical that the universe began with a big bang or that the earth is four-and-a-half billion years old.

At the Creation Museum in northern Kentucky, visitors can witness the Bible story of how the earth was created in just six days—literally six days.

CREATION MUSEUM VISITOR: The Bible is the Bible, you know. God created the earth and all of it in six days. Can’t argue with God.

PROFESSOR DARYL DOMNING: Creationism is a huge stumbling block for a lot of Christians in this country, and as a Christian myself I really find that regrettable, because it needn’t be.

SEVERSON: Daryl Domning is a vertebrate paleontologist in the College of Medicine at Howard University. He’s a devout Catholic and one of the scientists who will be helping seminary professors under the grant program. He has no problem with evolution.

DOMNING: I have found personally in my own faith life that a lot of Christianity, and Christianity in general, makes more sense in light of evolution than otherwise.

SEVERSON: Donshay Watkins is a second-year master of divinity student at the Howard University School of Divinity. She believes the earth was created in six days.

DONSHAY WATKINS: I’m not worried that I will learn anything to shake my faith, but I am excited about the possibility of expanding it.

PROFESSOR FREDERICK WARE (Associate Professor of Theology, Howard University School of Divinity): Sometimes faith has to be challenged in order for faith really to be genuine faith.

SEVERSON: Professor Frederick Ware is head of the Science for Seminaries program at the Howard Divinity School.

WARE: If it’s not a conversation that unsettles them, it’s very unlikely that they’re going to have an opportunity to grow, to broaden their horizons, to think differently.

METZGER: I would hope that I’m challenged at every turn, and that shows I’m alive.

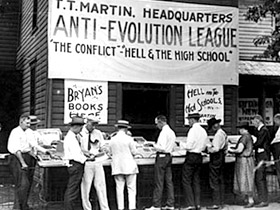

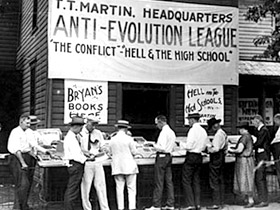

SEVERSON: The Scopes Trial, also known as the Scopes Monkey Trial, in 1925 had a huge impact on Christian fundamentalists. A high school teacher was vilified and found guilty of teaching evolution in Tennessee, which was illegal at the time.

(to student Matthew Riley): Do you believe in evolution?

MATTHEW RILEY III: I wouldn’t quite say that I believe in evolution.

SEVERSON: Matthew Riley III is a second-year divinity student at Howard and the son of a pastor.

RILEY: We have just started our studies in our systematic theology course in evolution and looking at how as ministers we can begin to incorporate some scientific theory in our ministry, but to say I believe in it is not something I’m quite ready to say.

WARE: The type of cultural warfare that’s taking place, and people are already settled into certain camps, I think that for us to talk about religion and science we have to deal with topics that have a broad base of appeal to people beyond just the battle between creationism and evolution.

SEVERSON: There’s a universe of questions about science that the seminaries will be looking into.

WISEMAN: If our earth is not the only inhabitable world, what does that imply?

METZGER: How does human life develop? How did the world develop? That’s certainly a key question that we hear about.

WISEMAN: We want pastors to understand how—what we know now in neuroscience and cognitive science can help them understand—how people respond in situations of distress.

METZGER: Matters of the soul—are we just material entities? What’s the difference between animals and humans?

SEVERSON: There’s another side of the equation: what can science learn from religion?

DOMNING: Science is good at coming up with the facts of the matter, but then where do we get our values, our means of making judgments about should we do this or not? And I think that’s the most obvious thing that the religious perspective can bring is a sense of values—a compass, if you will.

METZGER (speaking to students): Any other thoughts?

SEVERSON: Science for Seminaries is funded as a two-year project, but the hope, at least at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, is that it will expand to other seminaries and to more people of faith.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I'm Lucky Severson in Washington.