DAVID TERESHCHUK, correspondent: Stockholm this isn’t—in spite of the waterfront setting. It's Bay Ridge in Brooklyn, but it has something in common with that Scandinavian home of the Nobel Prizes. This New York City district is originating its own prize—for economics, and the beginnings of that prize lie in a local church.

REV. ROBERT EMERICK (preaching sermon): “To me the idea of a church offering an economic well-being award makes perfect sense.”

TERESHCHUK: Members of Bay Ridge United Methodist Church originally found themselves embroiled in controversy over the idea of getting involved in economic questions.

JULIE CUMMINGS: There are a lot of reservations about combining politics and church, things like economics and political parties—a lot of misgivings.

TERESHCHUK: The debate had begun with the minister, Robert Emerick, feeling bombarded by rival claims from politicians during recent election campaigns.

EMERICK: It seemed to me as a Christian minister that I needed to know whether the claims were true or false.

TERESHCHUK: Eventually it was agreed that the church should offer an economic well-being award, with a cash amount of $33,000. The church bought a large advertisement, a half-page in the New York Times, and invited economists, individually or in teams, to apply for the prize. The ad said the congregation wanted an economist’s clear and convincing explanation for why our economy is in such doldrums compared with a generation ago.

EMERICK: We’re asking for somebody to explain what are the factors, because every key economic indicator was stronger in that post-war period up to 1971, and every key economic indicator has been weaker since then.

TERESHCHUK: Pastor Emerick has no illusions that his church’s award is a match for the one-million-dollar Nobel Economics Prize, but he’s convinced that it has value.

EMERICK: Obviously there’s a difference in the amount of money. But above all we want it to be useful. We want to develop something that the average person can use, that you don’t need a PhD in economics to understand it.

TERESHCHUK: That demand for an understandable explanation is what won the day among doubtful church members. Their step into the public arena on economic matters is central to their faith, they say.

JOHN DONLAN: This thing that we’re doing now, it’s newsworthy. But I was thinking of things being God-worthy, and I think this, what we’re doing, is God-worthy.

TERESHCHUK: The Bay Ridge Methodists are no strangers to tough economic times. After giving up their former church, a historic building, because maintenance costs were too high, they now share space in a local Lutheran church’s property. And they say that just looking around their neighborhood has been enough to make them seek serious answers to their economic concerns.

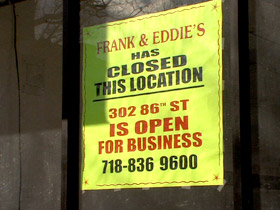

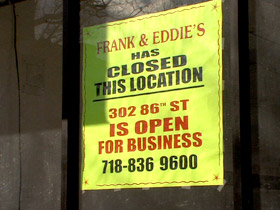

TOM McGIVERN: You see some stores that have been there for a long time that have closed down.

DONLAN: The rents are very high there. That’s why a lot of people, even though they put in a lot of hours, they work hard, to meet the rent it’s very difficult.

TERESHCHUK: And not just businesses, but ordinary families are also finding life hard.

KAREN McGIVERN: The kids getting out of college now. When I graduated college I could have gotten a job anywhere, no matter what kind of degree you had. Now they have all this debt, and they’re not getting the jobs.

SUSAN CICCOTTI: Things are much harder now. They really are, relative to what they were when I was growing up, you know, 20, 30, 40 years ago. My husband and I, we make a pretty good living. We are not poor, but we really truly live paycheck to paycheck.

TERESHCHUK: It could prove a bold challenge to the economics community, coming up with answers to satisfy this congregation.

TOM McGIVERN: For someone to be worthy of this award it needs to be a Nobel quality or beyond.

TERESHCHUK: Two hundred miles away, in Boston, a group of economists has emerged who feel they are up to the Bay Ridge challenge. For 40 years now they have been producing economics textbooks under the banner of “Dollars and Sense,” plus a magazine of the same name.

CHRIS STURR: There are a lot of kind-of smarty-pants economists out there who might be able to give their own theories, and they might be similar to ours, but our mission is to do it in an accessible way.

TERESHCHUK: Applicants for the Bay Ridge prize will likely focus on globalization as an explanation for today’s tougher times and the need for changing skill-sets among workers in a high-tech world. “Dollars and Sense” member Zoe Sherman wrote a cover story for the magazine’s anniversary edition that directly addresses Bay Ridge’s concerns—that life seemed more prosperous four decades ago. She emphasizes that though many more people might be going to work these days, workers’ income has not climbed along with that increase.

ZOE SHERMAN: Our labor force participation is higher than it was 40 years ago. So on average we’re all putting in more hours of market work, but without necessarily proportionally more reward.

TERESHCHUK: The “Dollars and Sense” group reckons that structural shifts in the economy lie behind many people’s smaller share in the nation’s wealth.

SHERMAN: If we add up a variety of different kinds of employment that are not very certain—what’s sometimes called the “gig economy,” people doing freelance work, picking up odd jobs here and there, and the self-employed, whose income can be quite variable and uncertain—that adds up to about 30 percent of the economy that does not have a predictable, regular paycheck.

TERESHCHUK: While such analysis may ring true to some of the Bay Ridge congregation, many are wary that the submissions they get from economists will be ideologically partisan. In fact, their announcement insisted they want a complete absence of ideology. How possible is that, in such a contentious field?

JOHN MILLER: I don’t think anyone can submit a nonpartisan submission, and I don’t even know what that would look like. I think the ideological lines are pretty sharply drawn now.

TERESHCHUK: But co-editor Sturr believes they can avoid political partisanship.

STURR: We think that the Democrats and the Republicans are equally, you know, at fault, or maybe not equally, but both heavily implicated in the policies that have led to our current economic predicament. And if ideology is kind of rigid thinking, we think that you need to be flexible in how you respond.

TERESHCHUK: For Professor Sherman, the very act of applying for the award will help her group’s overall aim: to involve regular people more fully in economic issues.

SHERMAN: The more people feel empowered to participate in the discussion of how our economic system should work and how they should be able to participate and what kinds of needs they need met by the economic system, the better we can do.

TERESHCHUK: This approach echoes Pastor Emerick’s original intentions, and he even thinks it might help the church and its members toward achieving a better economic life for themselves by getting a fuller understanding of finance and of their choices as voters between different economic policies.

EMERICK: And that’s our goal, to empower the average person to be able to make decisions and make judgments that are going to affect their life very deeply and the lives of their children and grandchildren, great-grandchildren.

TERESHCHUK: And for the congregants of Bay Ridge, it all fits with their desire as a community for a better life, materially as well as spiritually.

CUMMINGS: Economic well-being means people’s well-being. It’s my well-being, it’s John’s well-being, it’s Susan’s well-being and her children’s well-being, and it makes sense, I think, for a church to say, let’s come together, and let’s really try to think this out and think this through.

TERESHCHUK: For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is David Tereshchuk in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, New York.