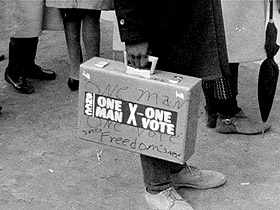

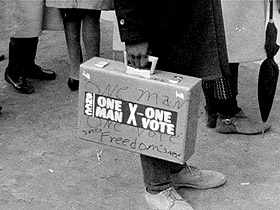

KIM LAWTON, correspondent: These marchers 50 years ago were rallying for a very political purpose: access to the voting booth. But many of them saw it as a deeply moral and spiritual crusade as well. They say it was their faith that ultimately enabled them to prevail.

REV. F.D. REESE: Had it not been for the Lord on our side we would have perished. We would not have been successful.

LAWTON: In the early 1960s in Selma, Reverend Frederick Douglas Reese was a school teacher, a pastor, and president of the Dallas County Voters League. In an area where segregation was slow to be dismantled, African Americans encountered many roadblocks when they tried to register to vote.

PROFESSOR GLENN ESKEW (Georgia State University): Only two percent of the black population in Dallas County was actually registered to vote in 1965. The realization was if we could get the vote then we could get political power, and if we could get political power, then we can change our society and our world.

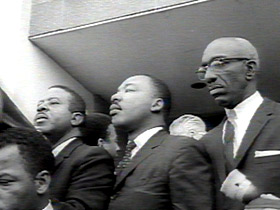

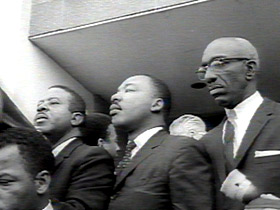

LAWTON: Student activists from around the country came to help local residents organize protests for the right to vote. Then in early 1965, Reese and some of his fellow pastors invited Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and his representatives to help raise the profile of the efforts.

REESE: We were determined to make sure that all people regardless of the color of their skin but by the content of their character, they would have an opportunity to participate in the political process that governed their lives.

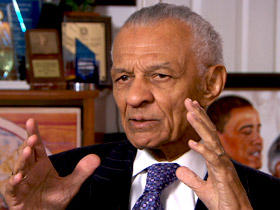

REV. C.T. VIVIAN: We are willing to be beaten for democracy.

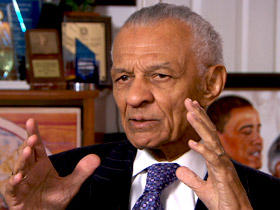

LAWTON: One of those who came to Selma was prominent civil rights activist Reverend C.T. Vivian, who led African Americans to the courthouse to try to register to vote.

VIVIAN: Whenever anyone doesn’t have the right to vote, then every man is hurt.

LAWTON: They were denied entrance by white police officers and Sheriff Jim Clark, who was known for beating the activists. Vivian forcefully confronted him.

VIVIAN: You are not as evil a man as you act. You know in your heart what is right.

LAWTON: After this confrontation, Clark punched Vivian in the face and had him taken to jail.

VIVIAN: I felt sorry for Jim Clark. Not at that moment. But it wasn’t … I wasn’t angry with him at that moment, alright? See, that’s what nonviolence does. It overcomes any hatred you have.

LAWTON: As was the case throughout the civil rights movement, organizational meetings and nonviolence training took places in churches, such as Selma’s Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

ESKEW: You had hymns that were sung, but instead of using the words of Jesus they were changed to words of freedom. You have preachers preaching, but instead of preaching salvation, they’re preaching civil rights. And you have altar calls, but instead of going down to confess and convert, you go down to volunteer and march.

LAWTON: As a young teen, Lynda Blackmon Lowery heard King speak at a church meeting was inspired to get involved.

LYNDA BLACKMON LOWERY: The right to vote meant that you could change things for the better. I knew then that I wanted to do whatever he was talking about. I really didn’t understand the importance of voting at 13, but I knew I wanted to do that.

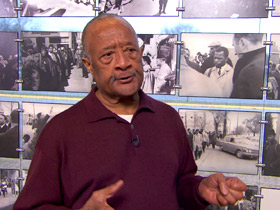

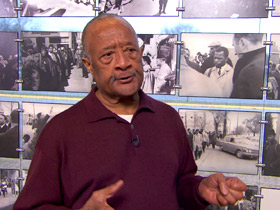

LAWTON: There were a series of mass meetings, acts of civil disobedience, and arrests in Selma. Then came Sunday, March 7, 1965. King wasn’t in town, but about 600 demonstrators gathered at Brown Chapel and then marched to the nearby Edmund Pettus Bridge. Seventeen-year-old student leader Charles Mauldin was near the front of the line.

CHARLES MAULDIN: When we were at the top of the bridge, the pinnacle of the bridge, we didn’t know what to expect until we got there. We looked down and saw the state troopers on their horses and the posse men, and that’s when we knew it was not going to be a very pleasant day.

SOUND FROM VIDEO: You are ordered to disperse. Go home or go to your church.

LAWTON: Within moments, violence erupted.

LAWTON: Mauldin says he wasn’t afraid, because he knew they had the moral high ground.

MAULDIN: Part of having a moral higher ground is that you don’t respect people enough to fear them. You’re willing to give your life, and once you’re willing to do that, then there is no fear.

LAWTON: Student leader and future congressman John Lewis was severely beaten on what became known as Bloody Sunday. So were dozens of others, including Lowery.

LOWERY: I ended up with 7 stitches over my right eye, and I still carry that scar. They shaved the back of my head, and I had 28 stitches back there, and I still have a knot in the back of my head from that.

LAWTON: The morning after Bloody Sunday, King sent an urgent telegram to clergy of many faiths across the country asking them to join him in Selma. He said “the people of Selma will struggle on for the soul of the nation, but it’s fitting that all American help to bear the burden.”

ESKEW: He’s saying come help us stand for what’s right, and they do. They come.

LAWTON: Vivian says many white churches initially had been reluctant to get involved in the civil rights struggle.

VIVIAN: They really didn’t have what it would take to change, because they had to be converted from the culture. Culture decided their religion, not Christ.

LAWTON: But Bloody Sunday became a turning point, and after seeing media coverage of the violence, people from many religious backgrounds were prompted to support the efforts.

VIVIAN: When you saw black and white together moving forward to get rid of segregation, get rid of misuse of people, when you saw it, right, it made a difference in all America.

LAWTON: In Washington, President Lyndon B. Johnson called for voting rights legislation.

PRESIDENT JOHNSON: It’s not just Negroes, really it’s all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.

LAWTON: On March 21st, just three weeks after Bloody Sunday, more than 3,000 marchers once again set out from Brown Chapel, this time protected by the National Guard. Over the next four days, 300 people would march the entire 54 miles from Selma to the state capitol of Montgomery. Lowery was the youngest person to march the entire route. She says she was scared, but a white fellow marcher helped allay her fears. It was Jim Letherer, an amputee who marched on crutches.

LOWERY: Jim said before he let anybody else harm another hair on my head, he would lay down and die for me.

LAWTON: On March 25, King addressed some 25,000 people in front of the state Capitol. For many of those who had gone through Bloody Sunday, the sense of triumph was overwhelming.

MAULDIN: There was no greater thought in my mind, no greater feeling in my heart, than to know that the nation had finally picked up our cause and were marching forward with it.

LAWTON: Five months later, Johnson signed the voting rights bill into law.

LOWERY: I was counting the years before I would be 18 and could vote. I knew that it was because of what had happened, what we did, the times we went to jail, the beating on Bloody Sunday. It was just because of us.

VIVIAN: That’s the beginning of the transformation of America. right? So that it becomes more like it says it should be.

LAWTON: Vivian says it’s imperative that religious groups today not lose focus on the importance of nonviolent direct action.

VIVIAN: We must get rid of violence. Not because of racism, but because violence is too destructive. You can solve social problems without violence.

LAWTON: Mauldin believes another enduring lesson is that young people can make a difference for good.

MAULDIN: If people as young as 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 could change a nation, then it’s all in their power to do the same. And I would encourage them to commit themselves to making this country a better place not for themselves but for everybody.

LAWTON: Many believe the civil rights movement can be a model for overcoming political cynicism.

ESKEW: It’s a marvelous movement because of the bravery, but also just the basic decency and the call for humanity to come together to make our world a better world; and a lot of that seems to be lost today, that we have society in a world in which consuming is everything and, and politics is something that many people don’t care to participate in.

LAWTON: He says the events of 50 years ago show a profoundly different way. I’m Kim Lawton in Selma.