In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

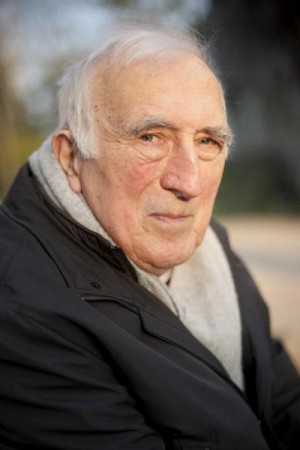

Jean Vanier Extended Interview

Read more of Judy Valente’s May 4, 2006 interview in Chicago with Jean Vanier:

Q: What are your feelings about what you have been able to accomplish?

A: I don’t know what I’ve been able to accomplish and I don’t know if I’ve accomplished anything. Because, you see, people come to L’Arche not because it’s going to give them status, but it’s because they feel called to it. And if L’Arche has developed 131 communities, it’s because people are called to that. And why are they called? It’s because people with disabilities have in some way touched them, transformed them. And so this is not my accomplishment. See, that’s where the whole paradox is: it’s not my accomplishment. I began, and then other people came; they were touched by Rafael and Philip. And so they stayed, and then others came, and they wanted to start the same community, because there’s something about a new vision. So it’s not my accomplishment.

Q: An assistant this afternoon said she sometimes thinks she could live the rest of her life in a large community and maybe not one more day. Can you talk a little bit about the difficulties and the pain of living in community?

A: I think the greatest pain is to lose the vision of why I’m there. And when you are losing the vision, what are you confronted by? People who are beautiful, but sometimes painful. I mean, there are explosions, there can be violence, there can be conflicts with other assistants. You can have fatigue and so, you know, let’s get out of here and do something else. There’s a sort of constant paradox that through all this suffering and pain and fatigue, [at] the same time we are seeing incredibly beautiful things, that is to say people who are transformed, and we are beginning to sense that we ourselves are transformed. There’s something that has changed within me, and it’s something about power, rivalry, competition — that it’s okay just to be myself. So we’re continually in this paradox of pain and suffering and yet resurrection. One of the things that are the most beautiful in L’Arche is when we celebrate. I mean, we have such fun together. We laugh, it can be, it could be moments of, you know, birthday parties, or when somebody’s been 20 years in L’Arche we have huge celebrations. Or it can be the way we celebrate Christmas, or whatever it is. There’s something so beautiful that we know we should be there. But there are other days where it’s so painful and we would like to run away, but we know we should stay there.

Q: You’ve written an entire book called BECOMING HUMAN. How do we become more human?

A: We become more human with two realities, one as we discover we are able to love people. And when I say “love people,” it means to see their value and their beauty. And that we can love people that have been pushed aside, humiliated, seen as having no value. And then we see that they are changed and at the same time we discover that we too are broken, that we have our handicaps. And our handicaps are around about elitism, about power, around feeling that value is just to have power and to have power is frequently to crush people. So we’re confronted by two visions, a vision of the pyramid, where you have to have more and more power to get more and more to the top. Or it’s about creating a body where every person has [a] place. So on one side we discover the joy of creating a body, and on the other side there’s this conflict because somewhere we also want to get up to the top and prove something.

Q: What is a heart-to-heart encounter? You have said that’s very important.

A: Fundamentally, it’s about trust. That you trust me, I trust you, and you know that I’m not going to reject you, that [I] know you’re not going to reject me. And you can tell me about your pain, you can tell me about what happened in your family, you can talk to me about the way you’d been hurt or rejected. And I can say things that I have lived. So somewhere there’s a truthfulness, a tenderness, and a trust. And then we sort of come together. Mother Teresa says something beautiful, she says: “You can begin with repulsion; if you get close to the body you touch compassion,” and then she says, “If you go a little bit further you have wonderment.” And that wonderment is that heart to heart, where I see and touch what is most beautiful in you, which is the child of God. And you see and touch in me what is most beautiful and most truthful[, which] is the child of God. And so in that movement one to another is the presence of God. It’s what Martin Buber says in the [book] I AND THOU, that there is nothing more beautiful than as we come together, you and I, in a moment of wonderment.

Q: When we visited the L’Arche community here in Chicago, we saw how important prayer is to the life of the community. You have said that prayer is more about listening than talking.

A: I mean, if God is, you don’t have to babble away. It’s about presence, see; everything is about presence. It’s to be present to God, and as soon as there’s presence to God there’s wonderment, there’s joy. Because somewhere we are caught up in the world of the finite and the contingent and the broken and the suffering and the pain, and prayer is this sort of opening of a door to something which is over and above and deeper, which gives meaning to all the pain of the finite. And yet it’s something that we can just rest in. I think fundamentally prayer is to rest.

Q: You have also said that there is a danger in religion if it closes people up. Where does that danger come from, and what did you mean by closing people up?

A: You see, somewhere we can create a group of religious people and think we are the best and the others are no good, and so in some way we’re trying to free ourselves from guilt. We want to pretend or live an illusion that we are the best. Somewhere the whole mystery of religion is that religion brings us to the presence of God, which is an opening up of my whole being to something over and above the immediate. And therefore we can rest and be open. You see, if God is the creator of heaven and earth and all the creation and the beauty of creation, it’s to go over [and] above the contingent and the difficult and to be in the presence of God. Friendship is a beautiful reality, but if we just spend our time flattering each other and thinking other people are no good, friendship begins [to be] something which is closed up, and it becomes dangerous. Religion can be a danger [when] I think I am the best, and I have to impose my vision upon you whether you like it or not.

Q: You have said that many people in the West have lost the meaning of life. What did you mean by that?

A: When I say “lost the meaning” — they’ve lost the zest for life. They’ve lost motivation. They are caught up in a very material reality, which essentially comes down to having more power and more wealth, instead of discovering that life is transmitting life. You see, the beauty of spiders is they give birth to spiders, elephants give birth to elephants, roses give life to roses, and we human beings, our capacity is to give life to others. But we can fall into productivity; we think that my glory and what is best for me is to create another car, or to build another thing — is to have more money. And we then lose the meaning of life, which is to transmit life. And the beauty of transmitting life is that I can’t control you. A mother cannot control her children, but they can give life and then help people to grow to freedom. We can destroy things, but life is something else; it’s a transmission of something, to give life and help people discover who they are so that they too can give life.

Q: How do we get the meaning of life back?

A: How do we get it back? Somewhere you begin to discover life when you fall sick, when you break your leg, when you’re closer to death — then you realize “I need you, I need people who trust me, I need people who love me.” I feel that most of the time to discover a new meaning we have to go through a crisis, we have to go through a breakdown. I’ll tell you an incredible story of a man called Aaron. I was in Ireland for what we call a festival of peace, and Aaron gave his message. He was an Israeli, and he said, “I have two sons. Both of them were in the army. The youngest one was killed by Hamas,” and he said, “I suffered terribly. He was a beautiful boy. My eldest son, he became so upset at the death of his brother and things that he had seen at the Gaza Strip that he became mentally sick.” The father said, “I’ve lost my two sons.” Then he said, “I met another man, Israeli, who had lost two sons in the army and we decided together to make an association of families for peace. We went to see Palestinians. We discovered Palestinians who had lost their father, their brother, their son. And so we created an association of Palestinians and Jews, so together we struggle for peace.” If that man had not lost his two sons, he would have remained behind the barriers between Israel and Palestine. But because he lost and [had] gone through pain, he didn’t let himself [be controlled] by pain. He didn’t let himself get angry, but he went into a movement of transformation. So, frequently we move from productivity to fecundity through a crisis.

Q: When you look at our world today, there are divisions of faith, violence, war, terrorism, genocide. Where is the world going, and how can it be healed?

A: You know, I was in the war [World War II], and people were saying the same questions. You go back [in the] history of humanity — it’s always been [the] same question. We can see all that is terrifying and therefore just [ask] that question: Where is it going? Or else you can see the trickle of peace, the trickle of truth, and there are many trickles of truth and of peace. Never in the history of humanity has there been a universal consciousness that people are sacred and important. Not everybody is following that. We have had genocides in Rwanda and the Balkans and God knows where. But somewhere there is a sense that the human person is important. So you find trickles of peace. You find that humanity has changed, like the Catholic Church has changed very fundamentally through Vatican II. I mean, there are changes everywhere. Barriers are breaking down, people are coming together. But this doesn’t mean to say you have no opposing reality of people wanting power and breakdown. I think every generation asks the same question. Maybe today because of the gravity of the armaments, in particular the nuclear armaments, because of our technology, because of television, we know more things. But still at the same time there are so many incredibly beautiful people and so many incredible, beautiful things. So where is the world going? On one side, it’s going empire to empire. Empires come, empires crash, empires that go back to the Spanish empire, the Portuguese empire, then the British empire. Now we have the American empire. But we see growing the Chinese empire, we see growing the Indian empire. Things will move, and so we’ll be continually in this — on one side, people wanting more and more power. But through that there will be lots of people wanting a trickle of peace, nonviolence, you see, these incredible movements of people saying, “We want now to learn to be universal brothers and sisters.”

Q: You’ve talked about the coming of the kingdom and the building of the kingdom, and yet you say most people who are Christians aren’t living as true disciples. What does it take to live as a true disciple, and how do you build that kingdom?

A: I always have to put things into context. You see, something about the kingdom is a vision of peace. You can read about visions of peace, but where do we see peace? It’s a world of conflict. And the kingdom is where we see a vision of peace and the vision of peace comes up from the bottom and not from up top. The whole of the Roman reality was “Pax Romana.” That is to say, to create universal peace through the armies of Rome. But, you know, a lot of people were angry with Rome, and the peace was imposed upon them. But there is another peace which comes from below, like the birth of the child brings peace to the mother, to the father. The kingdom [comes] through the little ones, through the weakest ones. You see, weak people bring down my defense mechanism; powerful people make me defend myself. Somewhere to become human is letting the defense mechanisms come down so that I can be myself. The kingdom is a place where we’re letting down our defense mechanisms, our need for power, because somewhere we have touched the joy of togetherness, and in that togetherness weak people have their place. Weak people are important. It’s not a pyramid, but it’s a gradual birth of a body, and the body will always be where the weak are. But we are in a culture of power, and the big [question] for Christians [is] how to live their Christian culture in a culture of power. Somewhere we have to become [a] counterculture — let down the barriers, the need for power, and then discover that life is to be celebrated together, where the weak and the strong can sing and dance together.

Q: You have dedicated your entire life to other people. You have never married, never had a natural family of your own. Any regrets?

A: I’m not sure I “dedicated.” I’ve been pulled into something. I’ve been attracted by something, and it’s very different. It’s not a sort of big choice. It’s to have felt led into something which is a mystery. And the difference between a mystery and a secret [is] once you get closer to the secret, nothing’s left. The more you get closer to a mystery, more becomes mysterious, a place of wonderment. So my sense over 42 years has been called into a mystery, which is the discovery [of] what is the gospel message, what is the kingdom? And how that togetherness with the little, the weak, and the fragile, we can build something beautiful together and celebrate life. I’d be crazy if I had regrets. That doesn’t mean to say I haven’t had to live through pain. That doesn’t mean to say I haven’t lived through conflict, that doesn’t mean to say I haven’t lived bad moments, but never regretting — how can you regret if you are having so much fun?

Q: What’s left to be done in your life?

A: Ah, to die quietly.

Q: What is the role of loneliness in life? What have you learned about loneliness through your work?

A: Loneliness brings you to anguish. Anguish can lead you to compensations — drink, drugs, even violence, to sexual encounters which have no fundamental meaning. But loneliness can also become a thirst, a thirst for meaning. It can even become a thirst for God. The whole of the Bible ends with the Spirit and the bride crying, “Come, come Lord Jesus, come!” And if the Spirit and the bride are crying, “Come, come Lord Jesus,” it’s coming from a terrible loneliness; it’s coming from an emptiness. When you cry out, it is, “I need your presence because I feel too lonely, and I feel too much in the world of anguish and inner pain.” I think one of the fundamental realities, and maybe the most complex, is how to live anguish. Not seeking compensations, superficial relationships, not filling ourselves up with television, but somewhere discover[ing] that it’s a cry for the infinite and [for] a presence. And it’s that cry which maybe is at the heart of the incarnation — that we want to discover and know a God who became flesh, not to manifest the power of God but to manifest love and togetherness and tenderness.