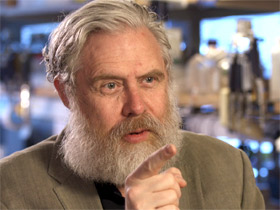

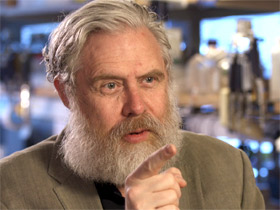

BETTY ROLLIN, correspondent: At George Church’s lab at Harvard Medical School in Boston, researchers are working on a wide range of projects, from slowing down aging to resurrecting extinct animals like the wooly mammoth. In order to do some of their work, researchers are using a two-and-a-half-year-old technique called CRISPR/Cas9, which allows them to identify a single defective gene among 30,000 and then cut and repair it.

GEORGE CHURCH (Professor of Genetics, Harvard Medical School): It is a machine that will search through every piece of DNA in a cell and can be programmed to hit a particular place and change it to whatever you want.

ROLLIN: What has scientists so excited is Crispr's potential. It’s simple to use and cost-effective. It can be used on adults to treat diseases that would affect only the individual being treated. But editing genes on human embryos, eggs ,or sperm, the genetic changes made would affect not only that individual, but all of his or her future descendants. These changes could potentially eliminate devastating genetic diseases like Huntington’s disease and cystic fibrosis. The earlier genetic changes are made, says Dr. Church, the better.

CHURCH: After the child is born, you might have to treat many cells in the body, and some of those treatments on that many cells could go wrong, and you have no real way of checking until the child develops cancer, or the adult. But if you do it at a single-cell stage, you can grow up a population from that single cell, and then you could check a few of those cells to make sure they are fine.

ROLLIN: Ethicist Marcy Darnovsky heads the Center for Genetics and Society in Berkeley, California, and is a critic of genetic editing.

MARCY DARNOVSKY (Executive Director, Center for Genetics and Society): Even if scientists are able to refine these gene-editing techniques so that they can more accurately place the new genes, or the replaced genes, we don’t know for sure what the effects of those genes are going to be once they’re inserted into the human genome.

ROLLIN: And that’s not the only concern. Many scientists worry that if Crispr can be used to eliminate certain diseases, it can also be used to make children smarter, taller, more beautiful.

Sound from clip of movie "Gattaca": Genetics, what can it mean? The ability to perfect the physical and mental characteristics of every unborn child.

ROLLIN: The 1997 science fiction movie Gattaca portrayed a society where genetic engineering was common. Marcy Darnovsky fears that this kind of genetic tampering could be something only the rich can afford.

DARNOVSKY: The worst-case scenario is that we would have these genetic haves and have-nots, and we already have so much inequality in the world. This would exacerbate that and could really...it’s creating an entirely new kind of inequality in the world and could lead to all kinds of discrimination, could lead to all kinds of conflict.

ROLLIN: George Church says he, too, has concerns but thinks the fears of Crispr have been exaggerated.

CHURCH: I’m concerned about every new medical technology has to be tested for safety and effectiveness. Crispr is no exception. I think the slippery slope argument I don’t buy. I don’t believe that because we can go at, you know, 200 miles an hour that every car is going to suddenly...every driver is going to do that. I think that there are all kinds of regulations in place for all of our technologies, and this should be and will not be an exception.

ROLLIN: But Marcy Darnovsky believes there is a safer alternative for parents who want to avoid a hereditary genetic disease.

DARNOVSKY: It’s called pre-implantation genetic diagnosis, PGD. It’s been in use for several decades, and you can look at the different embryos that are produced, and the ones that are not affected by the genetic mutation in question are the ones that you would then initiate a pregnancy with.

ROLLIN: More than 40 countries have put a prohibition on genetically modifying embryos. So far, the US is not one of those countries, nor is China where a recent experiment on embryos was performed and failed in almost every case, creating unintended mutations. Fortunately, only nonviable embryos were used.

Darnovsky and other prominent scientists have called for a moratorium on using gene editing on human embryos. And because of ethical and safety concerns, National Institutes of Health issued a statement saying the NIH would not fund any use of gene-editing technologies on human embryos. And according to a Pew poll taken last year, whereas 46 percent of adults approved gene editing to reduce risk of disease, 83 percent said doing so to make babies smarter is going too far.

One mother’s view:

RACHEL LACY: It makes sense, especially in preventing disease, but my gut response especially as a mother of these kids is they came perfectly the way I want them. I believe very, very much in God and that our bodies are made the way He made them, and even if they’re imperfect, we’re here on earth to prove that we’re worthy to be with Him.

ROLLIN: As long as the technology is there, controlling gene editing will no doubt be difficult, if not impossible. This fall, the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine will host an international summit to develop guidelines for editing human genomes.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Betty Rollin.