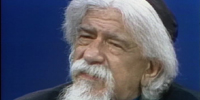

BOB ABERNETHY, host and correspondent: We have a profile now of the former chief rabbi of Great Britain, Jonathan Sacks. There is no one quite like him in the U.S. Sacks is a learned philosopher and Orthodox rabbi, the author of 25 books, with 16 honorary degrees. He is a newspaper columnist and a popular broadcaster who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth. He is also a member of the House of Lords. All that, and a sense of humor. Rabbi Sacks is teaching and lecturing in the U.S. this year [at New York University and Yeshiva University.] He was the keynote speaker at the Jewish Federation’s annual General Assembly and then taught a class where he recalled his knighthood ceremony.

RABBI JONATHAN SACKS: When you receive a knighthood you have to kneel, and Jews don’t kneel. On Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur we do, but any other times? No. So they provide this little thing which you hold onto, this little rail so you can incline yourself a little without actually kneeling, at which point, I’m sure you know, the Queen turned to Philip and said, “Why is this knight different from all other knights!”

ABERNETHY: That’s knight with a “k.” As Britain’s chief rabbi for 22 years, Sacks got to know many of the world’s leaders. He was widely respected and honored. And then he retired—to lead a global religious response to global religious violence.

RABBI SACKS: I am afraid that religion causes violence whenever we confuse piety and power. They are two completely different things. So when I seek power in the name of piety I do great harm. I injure God’s world. Fundamentalism, which is what we are talking about here, in any religion is always the product of fear, and I believe we have to allow faith to conquer fear. Somehow we have to let the better angels of our nature prevail over the fear that turns people into enemies. With religious movements it’s extremely hard to make peace, because peace demands a virtue called compromise, which to a religious mind is not a virtue but a vice.

ABERNETHY: And learning to respect each other’s religions—Jewish, Christian and Muslim—will take how long?

RABBI SACKS: I set myself up to kind of educate the educators of the next generation, and I don’t think there’s any shortcuts. There’s no quick fix here. You don’t suddenly turn radicals into moderates. You have to educate a generation.

ABERNETHY: That means we are looking at these atrocities for what, another generation or two?

RABBI SACKS: I suspect so.

ABERNETHY: Sacks insists that his message applies not only to Jews, but to others as well.

RABBI SACKS: I fight for the right of Christians to live their faith without fear anywhere in the world. But I need you Christians to fight for the right of Jews to live without fear anywhere in the world.

ABERNETHY: Sacks saw for himself the damage violent religious extremism can do when he visited ground zero in New York after 9/11.

RABBI SACKS: Murder of the innocent is forbidden in Islam. Suicide is forbidden in Islam. To be a suicide bomber is categorically forbidden in Islamic law. So you have here some religious radicals who are doing in the name of Islam what the leading teachers of Islam now and throughout the Muslim past have ruled to be categorically forbidden.

ABERNETHY: Sack’s hope that education can prevent violence is challenged by the Nazi Holocaust, which was supported by many of Europe’s most cultured and learned people.

RABBI SACKS: The more you study the Holocaust, the less you understand. I spent a lifetime studying it, and I still cannot understand. There were string quartets playing in Auschwitz-Birkenau while a million and a quarter human beings were gassed, burned, and turned to ash. What happened in Auschwitz in the Holocaust was a terrible demonstration of the limits of civilization to civilize if we do not fear God and see His image in every human person.

ABERNETHY: Now the Internet and social media are spreading anti-Semitism.

RABBI SACKS: The end result is that hostility anywhere can be communicated everywhere. I would not say its people are suddenly starting to hate Jews. It’s just a few people have learned how you can communicate hate very effectively and very widely.

ABERNETHY: Is anything like that happening in the United States?

RABBI SACKS: I can’t see how the United States can remain immune to it. Nobody is immune to it.

ABERNETHY: Sacks has deep praise for the ability of the U.S., over its history, to combine religion and freedom.

RABBI SACKS: If you want proof that you can be deeply religious and yet create a society that respects the freedom of the other, then you have to look here in America.

ABERNETHY: Sacks calls this a historic moment—challenging religious leaders to prevent the violent misuse of their own and everyone else’s faith.

RABBI SACKS: I think when the world, in Middle East, parts of Africa, parts of Asia are tearing themselves apart, of people fighting, wars of religion of the kind we have not seen since the 17th century, to get up and say to be a Jew is to be true to your faith and at the same time a blessing to others regardless of their faith. If people took that one sentence to heart it would change the world.

ABERNETHY: Which is just what Rabbi Sacks, in so-called “retirement,” is trying to do.