JUDY VALENTE, correspondent: On a sweltering Sunday afternoon, three generations gather for a family reunion. Christine Bennett’s parents moved to this African-American enclave in southwest Louisiana in the 1940s. They raised 13 children here.

CHRISTINE BENNETT: We had all our little stores. We didn’t go out of this little area for anything.

VALENTE: Concrete slabs mark the places where houses, businesses, and the post office once stood, giving Mossville the air of a ghost town. Bennett remembers her hometown as a verdant place where residents fished, listened to birds, shared homegrown vegetables, and lived long lives. But that was before the oil, gas, and chemical plants moved in. Fifteen of them in the past few decades. Now another plant is being built, one that turns ethane into a base chemical found in several consumer products, from plastic bottles to tires to paint. The plant will be the largest of its kind in the world and operated by a South African conglomerate called Sasol.

BENNETT: Once industry started coming in, people’s health started failing them. People were afraid of the explosions they were having. It was no more Mossville.

VALENTE: Faced with the public’s health and safety concerns, Sasol responded by offering to pay Mossville’s few hundred remaining residents to move away. Sasol’s plan underscores a classic economic dilemma: how to balance jobs creation, especially in poorer communities, with environmental and health concerns.

MICHAEL HAYES (Sasol Public Affairs Manager): We’re looking local first and trying to get as many local people qualified and hired into those long-term permanent positions as we can.

VALENTE: Sasol has promised to hire 500 local residents at its plant. Louisiana has one of the highest unemployment rates in the nation. But this part of the state experienced a nearly eight percent job growth in the past year. Environmentalists ask, at what cost?

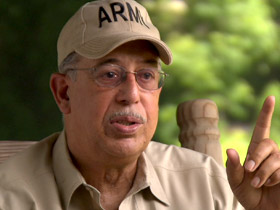

GENERAL RUSSEL HONORE (The Green Army): EPA and the state has given them exemptions to the Clean Air Act to dispose of 10 million pounds of toxins in the air per year.

VALENTE: Retired Army General Russel Honore heads an environmental group, The Green Army. Honore says the Sasol plant will also release 14 million gallons of hot production waste water into the nearby Calcasieu River every day.

GENERAL HONORE: It will change the ecosystem in that community. Now, that’s why when you go to Mossville you don’t hear the birds. They run out the birds, and now they are running the people out.

VALENTE: In 1998, a federal agency tested the blood of 28 area residents and found high levels of dioxins, chemical compounds that have been linked to cancer, diabetes, and reproductive problems. A 2009 study of 69 residents by a private consultant found half suffered from chronic eye irritation and skin rashes. Two-thirds reported muscle aches, sinus problems, and shortness of breath.

Hayes says Sasol has provided regulators with computer models that show its emissions to the air and water will meet or exceed EPA standards.

REP. MICHAEL DANAHAY (R): If you were to write a handbook about how to do what is right in a community or for a community, Sasol has written that handbook.

VALENTE: Still, residents are skeptical.

DOROTHY FELIX (President, Mossville Environmental Action Now): We’re human beings, and we know and we feel that our human rights are being violated.

VALENTE: Dorothy Felix is a longtime resident and head of the citizen group Mossville Environmental Action Now.

FELIX: It is sad to know that we are just being moved out without any choice.

VALENTE: When Sasol also announced plans to convert natural gas into diesel and jet fuel at a separate facility, many Mossville residents said they felt they had no choice but to seek a buyout by the company of their homes.

HAYES: The purpose of the Voluntary Property Purchase Program is to give people the opportunity to move. They asked for the opportunity to move, and we’ve worked out a program, the most generous program in history.

VALENTE: Sasol says it is offering property owners who live within a certain radius of its plant $100,000 plus 40 to 60 percent of the appraised value of their property. Many residents say it’s not enough to purchases homes in communities where property values are much higher.

GENERAL HONORE: If these people had done a mandatory evacuation they would have to pay them replacement value for their home, but guess what? This is a voluntary evacuation, and the politicians said, “You ought to be glad. Our good friends from South Africa are willing to buy you out.” Buy you out at their price.

VALENTE: Still, the company says the majority of owners have accepted the offers. The decision to stay or leave has been particularly traumatic for Mossville’s churches.

HAYES: It was only after the ministers came to us and said we’d like the opportunity to take our churches to a different location that we started working with them on a monetary value.

VALENTE: Where Truth Tabernacle Pentecostal Church once stood there is now an empty lot. At its new location, Truth Tabernacle has a spacious sanctuary and large meeting rooms.

REVEREND LIONEL THIERRY (Mossville Truth Tabernacle Church): I think it was a great opportunity for us to move out of a neighborhood that was diminishing into maybe a more flourishing neighborhood here.

MARY THIERRY (Mossville Truth Tabernacle Church): We’re probably going from 200 to hopefully 500 here.

VALENTE: The decision whether to move is far more wrenching for Mount Zion Baptist Church. Sasol offered Mount Zion $186,000 for the land, the church, and two substantial brick buildings on its property.

LASALLE CLARENCE WILLIAMS SR. (Mount Zion Baptist Church): We had some contractors that come in and just look around and said, “Now if we had to rebuild just like we got it here now, not add anything, what would it cost?” And they said “Well, two million dollars.”

VALENTE: Williams says it’s impossible to place a monetary value on the cemetery dating from 1866, where the church’s previous pastors and many members are buried. Many residents are also upset that Sasol has received lucrative financial incentives from local and state government. They include a 10-year exemption to paying property taxes, worth an estimated three billion dollars, and a $150 million grant in exchange for building the natural gas-to-fuel plant.

GENERAL HONORE: They have also declared certain parts heavy industrial and have given the company exclusive right to the roads, the public roads and the public utilities. So, in essence, they have created an environment that doesn’t look out for the welfare of the people, but looks out for the welfare of the company.

VALENTE: One of the last holdouts is Stacey Ryan, here taking a sample of water on his land to have tested. Ryan’s eighth of an acre abuts Sasol’s property. Because of the construction, his water and electricity have been turned off. He uses a generator, drinks bottled water, and uses rain water to wash. Access to his home is all but cut off by the construction. He’s been unable to get help in even to remove this tree, downed in a summer storm, from his front yard.

STACEY RYAN: They’re taking steps to make things hard for me in an effort to get me off my property. And also the offers that they did make, it doesn’t even amount to the things that I’ve gone through or what this property’s really worth.

VALENTE: Ryan says he suffers from diabetes and kidney problems. He once worked for Sasol and now blames the companies in the area for his and his family’s ailments.

RYAN: I haven’t seen a family member outside of two aunts and my grandmother live past their sixties.

HAYES: Two things about Stacey Ryan: One is that Stacey’s property is not located in the Voluntary Property Purchase area. Second thing is we are in negotiations with Mr. Ryan and his lawyer, and we are confident we will be able to reach an amicable settlement soon.

VALENTE: Right now, it seems all but certain the vast majority of Mossville residents will end up leaving eventually. And they will have only memories of their community.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Judy Valente in southwest Louisiana.