RABBI ANDREW BUSCH (Baltimore Hebrew Congregation): In this month of Elul, the Jewish month that leads up to Rosh Hashanah, we are using the prayer book both Friday night and Saturday morning as our Shabbat prayer book to familiarize people who come to worship.

We are a Jewish house of worship. Our prayer is Jewish, and yet we know, and openly embrace, those members of our community who aren't Jewish. And the book has to reach those different populations—younger, older, traditional families, nontraditional families, people who have doubts about God, and people who find belief in God very comfortable and easy.

RABBI HARA PERSON (Executive Editor, Mishkan Hanefesh Prayer Book): We really wanted to create a prayer book that is inclusive of the full range of who is in our community today. So it is LGBTQ-friendly. We're not going to say "bride and groom." We're going to say "couple." We have a blessing for people being called up to the Torah, a gender-neutral version. So somebody who isn't comfortable identifying by gender can still be called up, included, blessed, and have the honor of reading from Torah. The God language as well. So there are times where we do keep masculine language because we feel like it makes sense in this context. But there are other times where we use female language.

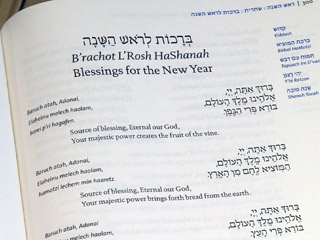

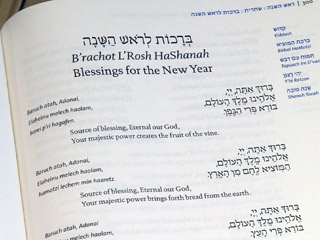

There's the sort of timeless pieces, which are the traditional prayers. Then there are the translations of those. There’s transliteration throughout the book, which is another kind of inclusive piece of it, because you can't...you know, it's hard to say to people "you are welcome, we want you to be here, we want you to feel included" if they can't read the text in Hebrew.

We have pieces at the bottom of the pages which offer a kind of philosophical, spiritual commentary, historical context. We offer the poetry, which goes to the same kind of the big themes, the big ideas.

We have artwork in the book. And for some people who are really visually oriented, these sort of beautiful abstract art, these shapes are going to be the same sort of thing that a poem would be...a kind of visual metaphor and another doorway into meaning and connection.

And there are meditations in the book as well. There are things that are not meant to be read out loud, but are meant to allow people to kind of rest in certain places, to maybe take a moment to have their own time of reflection or time for inspiration.

We embrace doubt. We embrace anger. We embrace ambivalence. We embrace discomfort. At its most literal level, Mishkan Hanefesh, means “sanctuary of the soul.”

The big eternal questions are still the same big eternal questions that our ancestors were grappling with—the nature of human existence, eternality, immortality, God. Those are timeless questions. But the ways that we connect to them are often different.

Certainly our approach to religion shifts over time. Not our core beliefs. Not our sort of core ethical values. Our core religious practices don't necessarily change. But the way we approach them, how we live them out in our lives, and the questions we ask about them, those I think change.

RABBI BUSCH: (Speaking to congregation) Today we stand before the shofar to hear its voice of hope.

CANTOR: Tekiah...(shofar sound)...Shvarim...(shofar sound)...

RABBI PERSON: There's a mix of, you know, wanting to enable people to stay where they're comfortable and where it's familiar. But also wanting to shake people out, into a new place, because I think change comes where we're uncomfortable. If we want people to truly go through the process of repentance, and all the sort of introspection and growth that you're supposed to be doing on the High Holidays, that is really about moving out of your comfort zone and into a new place.

RABBI BUSCH: A little discomfort's not a bad thing. The goal of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur is to remind us that we need to improve, and that each year we're given an opportunity to be reminded of that...and the work continues throughout the year in our actions, in our relationships, in our own thought processes.