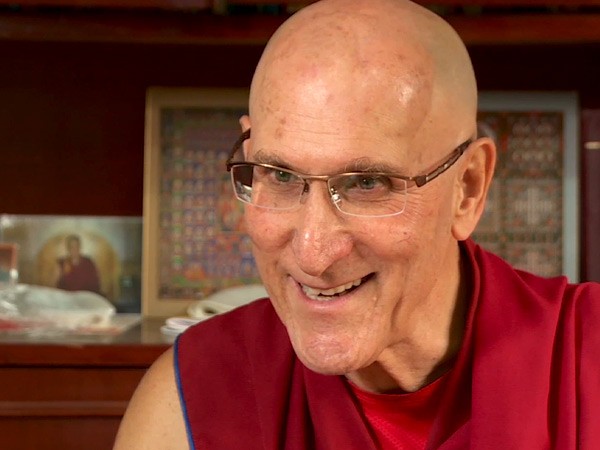

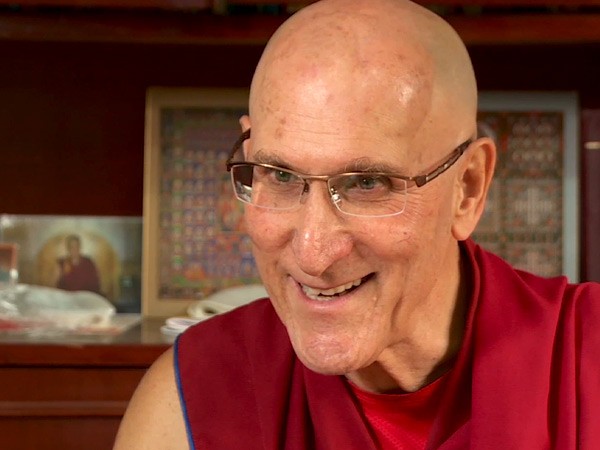

FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: Tucked into India’s side of the Himalayas, Dharmsala is home to the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s exiled leader, who settled here in 1959 after China took over his homeland. Today, the town is a mix of tourists, foreign and from elsewhere in India, Tibetan refugees, and practitioners and scholars of Buddhism from around the world, like Barry Kerzin. He’s long been a fixture here known to most as Dr. Barry. The 68-year-old California native is a family-practice physician. He began his career in academic medicine at the University of Washington, but never imagined it would lead to a pro bono, mostly house-calls practice conducted in Tibet’s main dialect.

DR. BARRY KERZIN: I keep pinching myself, Fred. I don’t know...

DE SAM LAZARO: He first came here after hearing that the Dalai Lama had wanted a doctor trained in Western medicine to teach traditional Tibetan medical practitioners in modern research methods.

DR. KERZIN: We did a research study, and we used that pedagogically to train the local Tibetan medicine doctors in how to do the research, and then I got more involved with Buddhism. I'd already been very interested. I got more involved with meditation, with study, and I ended up extending my stay, and that’s happened again and again, and here I am—27 years.

DE SAM LAZARO: He came here from a life punctuated by pain and loss: at 11, a near-fatal brain abscess that left a permanent lump on his skull. His mother, with whom he was very close, died prematurely, and a few years later so did his wife, in her mid-30s, both from cancer. Buddhism became a sanctuary, he says, under the tutelage of the Dalai Lama, who told him to stay connected to the world.

DR. KERZIN: He always encouraged me to keep my credentials and to continue practicing medicine: “Don’t just do the wisdom, also do the love and the compassion. In fact, do them fifty-fifty.” Those were his words: wisdom and compassion, fifty-fifty. It was like a lightning bolt, really, went through my heart.

DE SAM LAZARO: Scholarship in Buddhism led to his ordination as a monk by the Dalai Lama, and the extensive practice of meditation has been a path to inner peace and happiness, he says. And that’s translated into empathy—a particularly critical trait for a doctor.

DR. KERZIN: It’s moved me along slowly, moved me along to be more compassionate, to learn how to do that, be less selfish, to be less preoccupied with my own needs. I don’t get angry very much anymore. I used to be highly competitive. I'm still somewhat competitive but it's more now personal competition to better myself, not putting somebody else down, not at the expense of somebody else. I think it’s a combination of meditation and also as His Holiness calls it, “emotional hygiene.”

DE SAM LAZARO: In recent years, Kerzin, who now serves as personal physician to the Dalai Lama, has taken the spiritual leader’s gospel of “emotional hygiene” and compassion to medical practitioners around the world.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: [He is] my messenger. Go to Japan, go to Mongolia...

DE SAM LAZARO: And, full circle, to America...

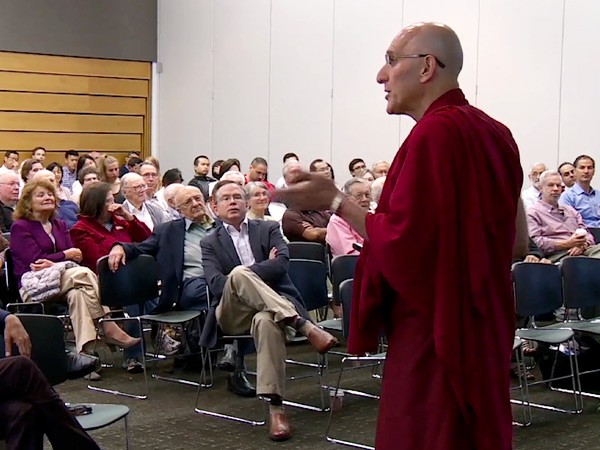

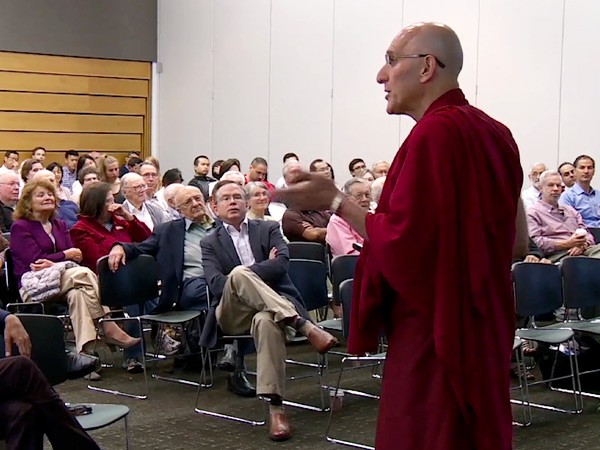

Dr. Kerzin: Good morning. It’s lovely to be here at Stanford...

DE SAM LAZARO: Until a few years ago, a prestigious Grand Rounds lecture at a top US medical school would have been unlikely for a message like his, from a man who left American medicine and many stunned colleagues for a lifestyle in which he doesn’t own a house, car, or refrigerator.

DR. KERZIN: I think initially they thought I went off the deep end: What are you doing living in India, come on! You know, how can you stay healthy? Why don’t you come back? You could have a very good life, you could have a very good academic life in medicine. You could have a very comfortable economic life. It’s ridiculous what you’re doing.

(speaking at Stanford): So let’s meditate, okay?

DE SAM LAZARO: But on this day they were listening—even meditating with him. Kerzin said meditation helps one focus on the “now,” the present. You tune out the past and all your regrets; tune out planning and worry about the future. It has taken years, he says, but gotten results. Scientifically measured results.

DR. KERZIN: This is in Madison, the University of Wisconsin, and they’re researching my brain.

DE SAM LAZARO: Kerzin was part of a noted study of the brains of people who meditate.

DR. KERZIN: What they found were changes in the pre-frontal cortex. This area is called “the executive function area,” the PFC, and it helps with things like planning, reasoning, imagination, empathy, to feel like another person is feeling. So these areas were enhanced, both anatomically and functionally, in long-term meditators.

DE SAM LAZARO: Kerzin’s host at Stanford said one reason his message resonates is what he calls “an epidemic of dissatisfaction” among American doctors today.

DR. ABRAHAM VERGHESE: Fifty percent of them, they say in some studies, are unhappy. And that tells you this is not an individual problem. This is a systemic problem.

DE SAM LAZARO: Dr. Abraham Verghese, a best-selling author and professor at Stanford, says technology, for all its diagnostic benefits, leaves doctors little time for the empathy that drew most of them to medicine.

DR. VERGHESE: There was a chilling paper from the journal [American Journal of] Emergency Medicine titled “4000 Clicks,” suggesting an emergency medicine physician does 4000 clicks a day and spends the great majority of their time on the computer, very little percentage of the time actually with patients, and similar studies that are coming out suggesting the same about residents and medical students and physicians and other specialties...

DE SAM LAZARO: Kerzin says wants to make compassion as integral to medical education as physiology or biochemistry. And he says he wants to build more partnerships between scientists and Buddhist scholars, a reconciliation of very different perspectives on life that he says he's made internally.

DR. KERZIN: I used to say I wear two hats. So sometimes this is the medical hat, this is the Buddhist hat. But I don’t say that any more.

DE SAM LAZARO: For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Dharmsala, India.