FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The Spanish began arriving in Saltillo in the late 1500s. In the late 1990s, the trains began arriving as the city became a major North American freight trade hub. Today thousands of rail cars carry goods made in Mexico north to the US. They also carry undocumented migrants from Central America. Many will hop off in Saltillo for the final 200 mile stretch to the Texas border, hoping to avoid not just Mexican and US authorities but also criminal gangs.

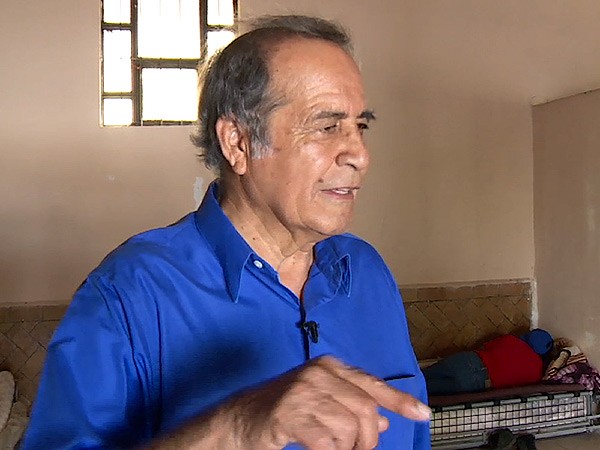

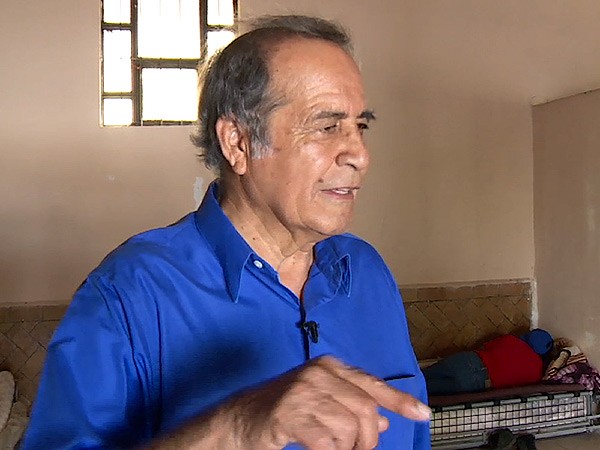

One of the few safe harbors here is the Casa del Migrante, started by 72-year-old Pedro Pantoja, a Jesuit priest.

REV. PEDRO PANTOJA: Every migrant is a potential kidnapping victim, and the criminals extort up to $5000 in order to set them free. In the first six months of 2009, we know of about 9000 migrants who were kidnapped. In that six months, that was worth $25 million for organized crime.

DE SAM LAZARO: And now, he says, they must contend with immigration authorities in Mexico. With pressure and aid from the US government, Mexican authorities have been clamping down on Central American migration, and the number of people making it as far north as the US border has dropped significantly. But they haven't stopped coming.

REV. PANTOJA: These guys are really tired. They just got here early this morning.

DE SAM LAZARO: The new arrivals eluded the Mexican migrant dragnet which deported 25,000 Central Americans in the first two months of 2015, double the number from a year earlier. Unaccompanied minors, thousands of whom were once reaching the US, are intercepted long before they could get this far north.

Why do they persist, I asked?

REV. PANTOJA: The answer is what one migrant said to me: “Yes, I fear organized crime, I fear the police, but I fear hunger more, and violence.” They are the strongest motivators.

DE SAM LAZARO: Many of the mostly male migrants say they’re fleeing conscription into the criminal gangs that now dominate urban life in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, a region with the world’s highest homicide rate.

REV. PANTOJA: They have young gang members on every street corner, and they know exactly who lives in every house, who goes in and out.

DE SAM LAZARO: This 22-year-old wanted his identity concealed to protect family back home. He escaped El Salvador only to be apprehended along with four fellow migrants by Mexican police along their train journey. They weren’t arrested but were instead stripped, forced into a nearby pond, and robbed, he told me.

Migrant from El Salvador: They took all of our money, our phones, shoes, and they threw our clothes in the water. They were laughing at us.

DE SAM LAZARO: They found refuge in a church, he said, and were eventually referred to this shelter.

REV. PANTOJA: We get the details of each person. This allows me to communicate with their families if they get kidnapped, if they die, if they end up in jail or get lost on the route.

DE SAM LAZARO: Santos was being registered on this morning.

FEMALE EMPLOYEE: From which country?

SANTOS: Honduras.

FEMALE EMPLOYEE: And a telephone number that we can reach loved ones?

DE SAM LAZARO: He’s hoping to return to Texas where he worked undocumented for years before a fateful traffic stop led to his deportation. Going to the US is far more perilous now, he says.

SANTOS: In the nineties, you could easily cross. Now they own the river. If they catch you they’ll beat you up, even kill you. The only way now is to find a good coyote.

DE SAM LAZARO: Coyotes, or traffickers, usually tied to gangs, charge about $4000, he says, though other reports put the price tag much higher—with no guarantees. Santos tried once before, in 2010, and did make it into the US, barely, but was immediately caught and sent back by the border patrol.

Why do you want to take the risk, given how dangerous this journey is?

SANTOS: Because the situation in Honduras is that for a 46-year-old, no one will give you a job in my line of work, construction. If you try to start your own business, no matter how small, the gangs who would extort any earnings.

MAVER: My life was threatened by the gangs because I couldn’t afford to pay the extortion.

DE SAM LAZARO: Thirty-six-year-old Maver also fled Honduras, leaving behind her small shop and two older children. She brought her three-year-old, Emily, on a journey that turned from tiring to terrifying. She says Emily was snatched from her by men who’d posed as good Samaritans offering to help them.

MAVER: It was about 3:30 in the morning. It was really dark. That’s when they came and took my child. They shoved me to the ground, took the child, and said I had to pay $10,000 to get her back.

DE SAM LAZARO: Sensing her anguish, the often hostile Mexican authorities were sympathetic, she said, as were many strangers.

MAVER: I’ll never forget being in church on Mother’s Day and watching all these mothers with their children and wondering, where is my child?

DE SAM LAZARO: In the end, Emily was found in the custody of child protection authorities, apparently turned over by her kidnappers, though no one will say, and the child does not remember.

MAVER: The moment I lifted her up was the happiest moment of my life, to hug her, to know she was alive. Emily told me she was very scared, kept saying, "Why did you leave me to travel by myself? Why did you leave me alone?" Now every time I hug her I tell her she’s not alone.

DE SAM LAZARO: With so much worry about crime, it’s easy to forget that the journey—walking and stowing away on freight trains—is physically tiring and dangerous. Getting your leg jammed between train cars, for instance. That happened to 50-year-old Laura, who then fell to the ground in excruciating pain.

LAURA: I thought I was going to die, and all I kept thinking was, let me die in a town so they’ll be able to identify me and take me back to my family. And then I saw a man and shouted for him, and he called the Red Cross.

DE SAM LAZARO: After three days in the hospital, she was brought here, where she’ll wait several months for her wound to heal, for a prosthesis, and then rehab. After that, she says she’ll continue her journey north.

LAURA: I know it will be more difficult, but what else can I do? I have to support a family, not just my daughter, but I have grandchildren. They don’t even have a place to live.

DE SAM LAZARO: She can stay here for as long as she needs. Unlike other shelters along the long migrant route, this one has no time limit.

REV. PANTOJA: All people who come here injured or hurt, they do not leave here until they’re completely recovered. They have to leave here as persons who are free and with dignity.

DE SAM LAZARO: Some migrants engage in crimes, he said, but the numbers are grossly exaggerated. Over the years he says the shelter has convinced a once skeptical and fearful local community to support his work—now with donations of cash and kind and moral support that helps protect it from local gangs.

REV. PANTOJA: In Genesis chapter 12, God called Abraham to be a migrant. In reality we are all migrants...

DE SAM LAZARO: But with varying fortunes. The shelter helped Maver and Emily get a humanitarian visa to legally be in Mexico. That will allow her to make a much safer bus journey to Texas. Guadalupe Arguello, who works at the shelter, says Maver has a decent chance to plead her case for asylum, based on the threat to her life.

GUADALUPE ARGUELLO: In our experience, based on the experience of other mothers with children, yes. Also, she has family in the US who will help her financially and legally.

DE SAM LAZARO: That’s not an option for Santos, who was preparing for the perilous hike to the US border. His main task: to find a trafficker with both a good track record getting people across and one willing to take most of the payment once Santos gets there.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Saltillo, Mexico.