TIM O’BRIEN, correspondent: It was in 1986 in Rome, Georgia. Eight-thirty at night. Seventy-nine‐year-old Queen White had just returned home from choir practice to confront a burglar who would take her life.

Prosecutors said it was this man—Timothy Foster—18 years old at the time. They say he bashed her skull with a fire log and then strangled her. She had also been sexually molested.

Down at the Floyd County Courthouse, and over the vehement objections of defense lawyers, prosecutors excused all African Americans from the jury pool. Foster would be tried, convicted, and sentenced to die by an all-white jury.

The US Supreme Court had ruled only four months before this crime was committed that while lawyers have wide latitude in selecting juries and may even excuse some prospective jurors without having to explain why, race can never be a factor. Should it appear that race is the motive, the attorney must be able to provide race-neutral reasons:

STEPHEN BRIGHT (President and Senior Counsel, Southern Center for Human Rights): The reasons given here—some were false. They simply weren’t true. Some were contradictory. In fact, on their lists of people who they were definitely going to strike, the five African Americans were the first five listed. And there was only one other person on the list, a white woman. So the priority was to strike all the blacks from the jury.

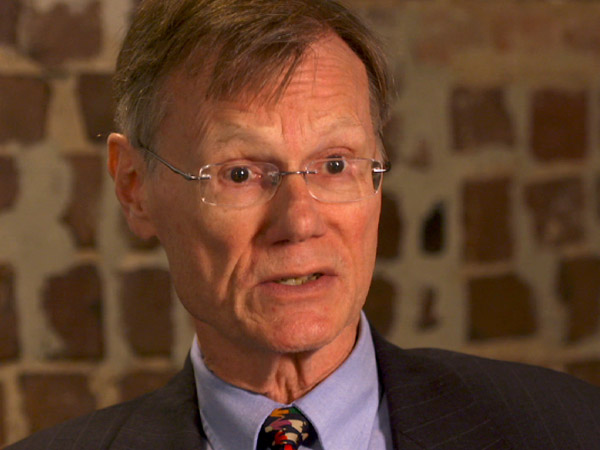

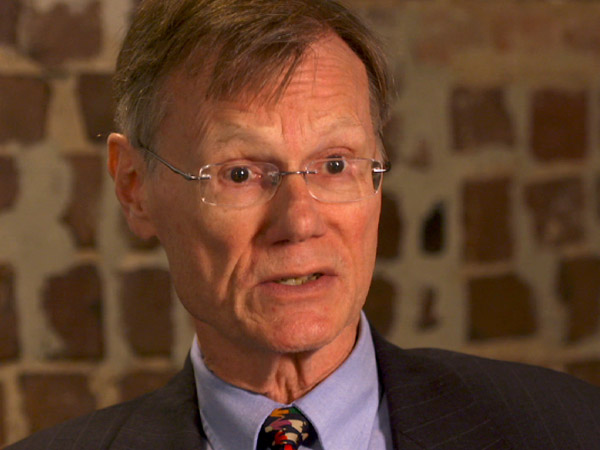

O’BRIEN: Stephen Bright runs the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta and will argue Foster’s case before the Supreme Court. Proving jurors were removed because of their race can be difficult, but lawyers at the Center say they have come up with some persuasive new evidence:

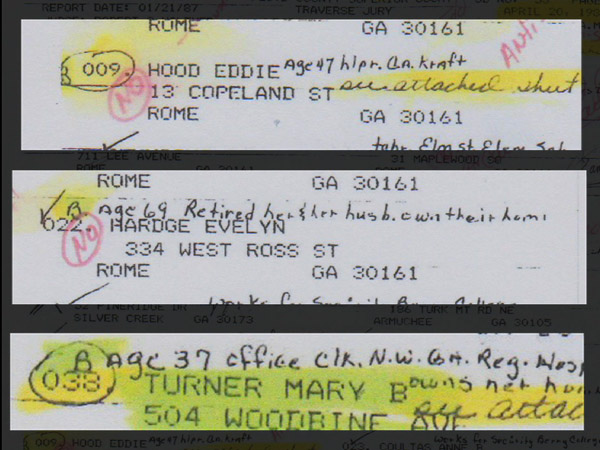

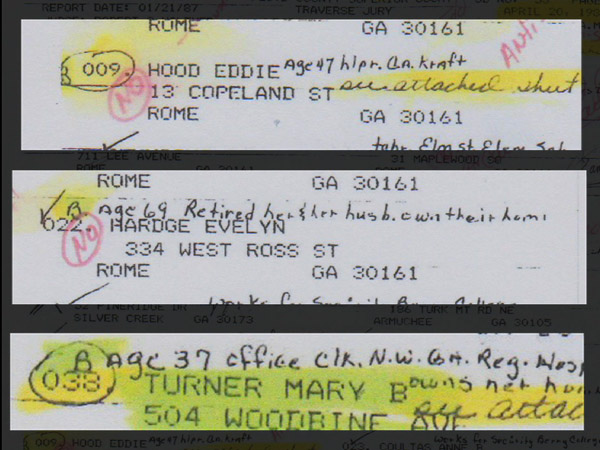

BRIGHT: Well, what we found was the prosecutor’s files, and in the prosecutor’s files, they had listed—they race-coded and color-coded—all the black people in the lists of the jurors. They had identified jurors with things like B-1, B-2, B‐3. They had compared the black jurors against each other in the notes, saying, “If we have to accept a black, maybe this one would be OK, which suggests the goal was to get rid of all the blacks. And so, when you add it all together and look at all of the evidence together, it all points pretty much in one direction, which is race.

O’BRIEN: Lawyers for the state declined to be interviewed and referred us to the brief they have filed in the Supreme Court in which they deny any wrongdoing. A ten-year study of 332 criminal cases in Louisiana found that the likelihood of acquittal does go up significantly with the number of blacks on the jury. When there were at least three blacks on the jury, 12 percent of the defendants were acquitted; the acquittal rate rose to 19 percent with five or more black jurors, and no one was acquitted in the study when there were two or fewer black jurors. In all three groups, the defendants were overwhelmingly black.

KENT SCHEIDEGGER (Legal Director, Criminal Justice Legal Foundation): So if the prosecutor is entirely, legitimately trying to remove those jurors that he believes are more likely to be opposed to the death penalty, the natural effect of that is going to be that you will use more preemptory challenges against African-American jurors. But that's legitimate. That’s how the system works.

O’BRIEN: Kent Scheidegger is legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, a victims’ rights group that supports capital punishment, and Scheidegger says the fact that prosecutors kept notes on the race of the jurors doesn’t prove racial discrimination, but rather may help to refute it.

SCHEIDEGGER: The fact that you keep track of the race of the jurors as you go through the process is not at all suspicious. In order to defend yourself against the charges of discrimination, you have to keep track. That’s why every time we apply for a loan, or a job, or school admission, we’re asked to specify our race, and that’s all they were doing in this case.

BRIGHT: If all you wanted was to know information about the black jurors, you wouldn’t write things like, “If we have to accept a black, maybe this one will be okay.”

O’BRIEN: You really don’t know what’s going through the prosecutor’s mind.

SCHEIDEGGER: Right.

O’BRIEN: Unless you have a mind reader.

SCHEIDEGGER: Right.

O’BRIEN: You want his conviction set aside.

SCHEIDEGGER: Right.

O’BRIEN: But what more than that? What do you want the Court to say? What rule would you have them announce?

BRIGHT: Always in these cases, what the Court says about jury selection, and what it says about the reasons that prosecutors have to give for striking people of color from juries, that’s going to affect every case from now on. And one of the things that I hope at the very least will come out of this case is that the Court will require the reasons given be scrutinized much more carefully than they were in this case.

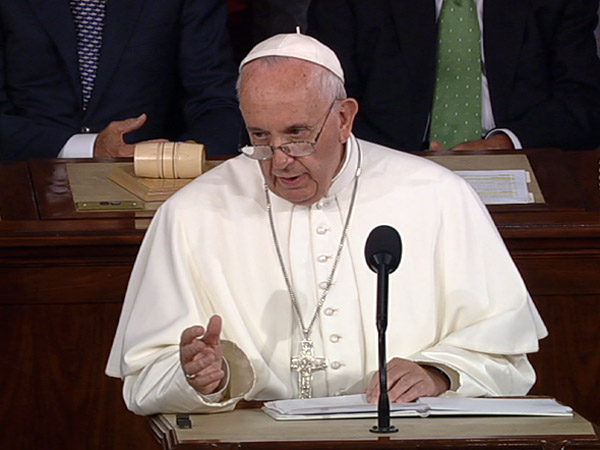

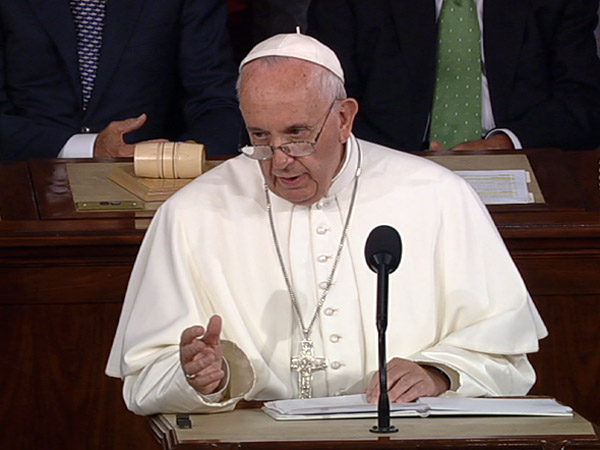

O’BRIEN: The Foster case goes before the Supreme Court at a time of dwindling executions in the US and growing opposition to capital punishment. On his recent visit to Washington, Pope Francis called for worldwide abolition out of respect for human life:

POPE FRANCIS (speaking to the US Congress): “This conviction has led me from the beginning of my ministry to advocate on different levels the global abolition of the death penalty.”

O’BRIEN: The pontiff’s appeal is not likely to have an impact at the Supreme Court level, even though six of the current justices are Catholic—more Catholics than at any time in the country’s history. Here, the issue is not what states “should” do, but rather what the Constitution—and its ban on "cruel and unusual punishment"—forbids them from doing. And significantly, last June, two justices formally urged the Court to reconsider whether the United States is even capable of administering capital punishment in a constitutional manner. The justices, Stephen Breyer, joined by Ruth Bader Ginsburg—both of whom happen to be Jewish—noted: that the risk of executing an innocent person remains great; that factors such as race, gender, and geography make the death penalty arbitrary; that the decades’ long delays between sentence and execution defeat the goals of deterrence and retribution; and that both death sentences and actual executions are becoming increasingly unusual—down almost 70 per cent in the last 15 years.

JUSTICE BREYER: "I recognize that we are a court, not a legislature, but the matters that I have discussed are judicial matters. They concern the infliction of an unfair, cruel, and unusual punishment upon individuals at odds with a specific constraint that the Constitution imposes on the Democratic process."

O’BRIEN: It is widely believed that two other more liberal Justices on the Court, Sonya Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, may share those views although they have yet to formally declare their position.

The country appears to be slowly, but inexorably, moving away from capital punishment. If so, the US Supreme Court may not be too far behind.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I'm Tim O'Brien in Washington.