In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

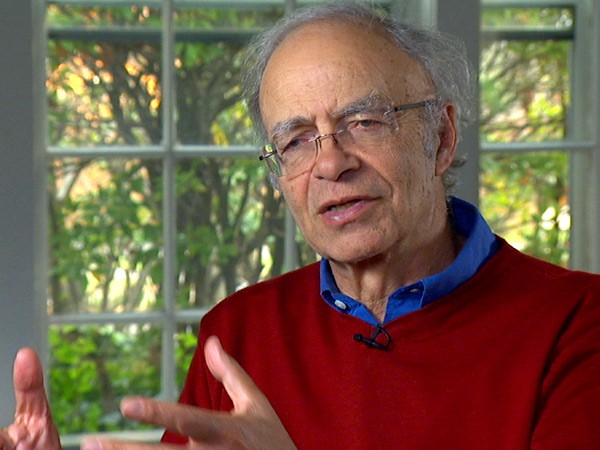

Peter Singer on Effective Altruism

Princeton University ethicist and philosopher Peter Singer, author of The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas about Living Ethically, explains effective altruism as using means-testing and market research to measure the effectiveness of charities, and then giving money to those organizations that can do the most good. Singer says when people become more generous and give more to others, it actually adds to their own happiness.

Read an excerpt from The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas about Living Ethically (Yale University Press, 2015) by Peter Singer.

At the core of the reasonable person’s ethical life is a recognition that others are like us and therefore, in some sense, their lives and their well-being matter as much as our own. Therefore the reasonable person cannot have self-esteem while ignoring the interests of others whose well-being she recognizes as being equally significant. The most solid basis for self-esteem is to live an ethical life, that is, a life in which one contributes to the greatest possible extent to making the world a better place. Doing this is not, therefore, altruism in a sense that involves giving up what one would rather be doing, nor does it involve alienation or a loss of integrity. It is, on the contrary, the expression of the core of one identity.

If effective altruists are not making a sacrifice, do they deserve to be considered altruists at all? The idea of altruism always has in it the idea of concern for others, but beyond that, understandings can differ. Some interpretations imply a complete denial of one’s own interests in order to serve others. On this view, if the rich man were to do as Jesus told him—to sell all he has and give the proceeds to the poor—he would still not be an altruist because he was asking Jesus what he must do to inherit eternal life. Similarly, on a Buddhist view, helping others and protecting life advances one’s own well-being too. If one can, through virtuous living and meditation, achieve enlightenment, one transcends one’s ego and knows the sufferings and joys of every sentient being. There is no sense of loss in this transcendence of the quest to satisfy desires that previously seemed so important or of the pleasures that came from their satisfaction, for enlightenment involves detachment from one’s desires.

We do not have to make self-sacrifice a necessary element of altruism. We can regard people as altruists because of the kind of interests they have rather than because they are sacrificing their interests. A story told about the seventeenth-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes illustrates this point. During his lifetime, Hobbes was notorious because his philosophy was based on egoism, the idea that people always do what is in their interests. One day while walking through London he gave alms to a beggar. A companion immediately accused him of refuting his own theory. Hobbes replied that it pleased him to see the beggar made happy, so his gift was consistent with egoism. But now imagine that Hobbes did this all day, every day; that he actively sought out people in need and offered them assistance, to a point at which he reduced his fortune and lived more simply so that he could give more. He continues to explain his actions by saying that his greatest joy comes from seeing people made happier.

Is this imaginary Hobbes an egoist? If so, the claim that we are all egoists has been weakened to the point that it no longer shocks. On this understanding of egoism, the apparent dichotomy between egoism and altruism ceases to matter. What is really of import is the concern people have for the interests of others. If we want to encourage people to do the most good, we should not focus on whether what they are doing involves a sacrifice, in the sense that it makes them less happy. We should instead focus on whether what makes them happy involves increasing the well-being of others. If we wish, we can redefine the terms of egoism and altruism in this way, so that they refer to whether people’s interests include a strong concern for others—if it does, then let’s call them altruists, whether or not acting on this concern for others involves a gain or loss for the “altruist.”

— The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas about Living Ethically (Yale University Press, 2015) by Peter Singer