LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: Walmart is big. The retailer has over 11,000 stores in 28 countries, with revenue of nearly $500 billion and more employees than Rhode Island has citizens.

Walmart is also one of the country’s biggest gun dealers, so there was jubilation in some circles in the fall of 2015 when the company stopped selling high-capacity assault rifles. Evan Davis is the chancellor of Trinity Church in New York.

EVAN DAVIS (Chancellor, Trinity Church Wall Street): And it’s a double win, because it helps the community, and it helps the company, and from our point of view that’s what corporate social responsibility is all about.

SEVERSON: On the other side, people like Michael Hammond, legislative counsel for the Gun Owners of America, thinks churches like Trinity ought to stick to preaching the gospel.

MICHAEL HAMMOND (Legislative Counsel, Gun Owners of America): I think it needs to determine whether it’s going to serve God or mammon.

SEVERSON: You referred to it as a temple of political liberalism.

HAMMOND: Yes, I did.

SEVERSON: Hammond is sore at Trinity because the church was deeply involved in trying to influence Walmart’s policy on selling high-capacity rifles. It’s just one example of faith groups investing in corporations and working to influence corporate decisions.

The Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility, or ICCR, was one of the first to encourage socially responsible investing. ICCR is a coalition of 300 faith-and-values-based organizations, ranging from evangelical Christian to Muslim. David Schilling is a United Methodist minister.

REVEREND DAVID SCHILLING (Senior Program Director, ICCR): We’re looking at it from the perspective of a broader sort of moral frame in terms of the social and economic justice issues, and that’s not necessarily easy for companies to initially absorb.

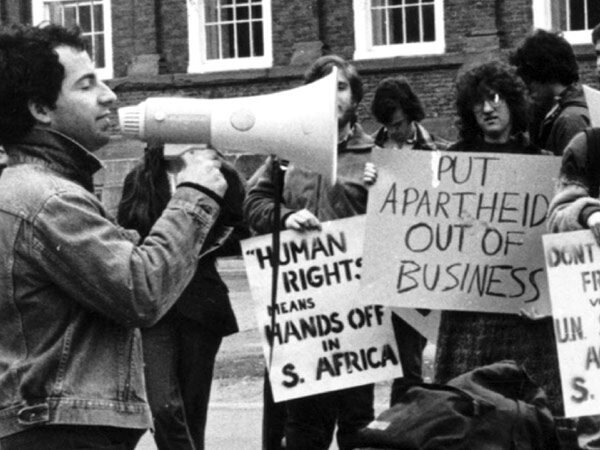

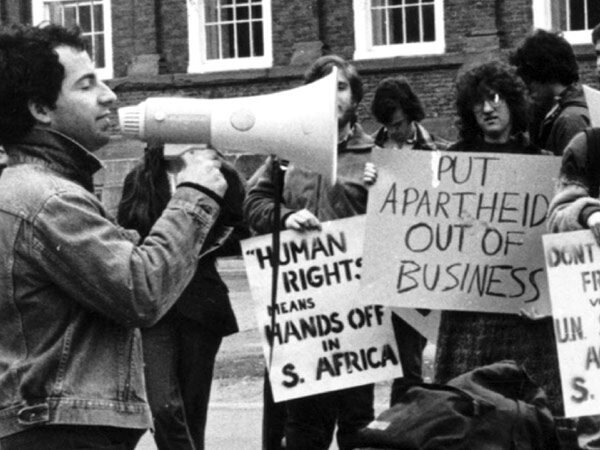

SEVERSON: ICCR has been at work behind the scenes for over 40 years, involved back then in persuading American corporations to pull out of South Africa during white supremacist rule.

SCHILLING: The South African Council of Churches, they’re saying to ICCR, “Listen, you need to really address this issue. It’s just—it’s hurting us, it’s killing us. We want companies to withdraw.”

SEVERSON: ICCR has waged an inside battle for reform with major United States corporations. Those, for instance, who do business with apparel companies like the ones in Bangladesh who lost more than 1,100 workers in a collapsing sweatshop building that was a death trap. ICCR is currently working to rein in companies that are engaged in what it calls modern slavery—the trafficking, Schilling estimates, of at least 21 million people.

SCHILLING: The core here is if companies that ICCR members are invested in have global supply chains—agriculture, electronics, apparel, construction, food and beverage—it just goes on—you are likely to have trafficked workers at the base of that supply chain.

SEVERSON: The center works with companies it wants to behave with greater social responsibility. The financial meltdown of 2008 took its toll on public trust in the country’s banks. This is Father Seamus Finn, who chairs ICCR’s board.

REVEREND SEAMUS FINN (Board Chairman, ICCR): It’s always a question of whether Congress or the banking sector has a better rating in the mind of the American public. But restoring confidence in these institutions because it was so absolutely just devastated is going to take a while.

SEVERSON: The center’s approach seems to be working, even though members rarely hold press conferences or attack corporations publicly. They do their work from within. They are, after all, active shareholders. Cathy Rowan of ICCR works with the health care industry.

CATHY ROWAN (Member Representative, ICCR): We come from the perspective of being long-term shareholders, which, when we say that often to companies, they’re quite relieved because there is so much pressure for that next quarter and hitting those earning marks.

FINN: I think our argument has been quite simple, that the more a company is able to integrate a good, solid social and environmental policy and governance policy into their model of business, then they will be around a lot longer.

SEVERSON: Reverend Bill Lupfer is the rector of Trinity Church

REVEREND WILLIAM LUPFER (Rector, Trinity Wall Street): I’m a governance guy, and I think good governance builds trust, and so trust within Walmart, trust within Walmart and their customers. If we’re an investor we want that kind of trust.

DAVIS: We wouldn’t be investing in Walmart if we didn’t think it was a good investment, a company with both a great present and a great future.

SEVERSON: Trinity has been invested in Walmart for many years, and after the Sandy Hook School shootings, the church decided it had to do something.

DAVIS: These are weapons that, you know, fire so many rounds so quickly—bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang—that you can kill a lot of people before anyone has a chance to overcome the shooter while they’re reloading. We think there that the danger to the community outweighs the sporting interest, the hunting interest, that kind of thing.

SEVERSON: Walmart refused to budge, so Trinity sued in court and won, then lost on appeal. But the Securities and Exchange Commission then ruled that Trinity as a shareholder has a right to present social justice issues, and the company should consider them. Walmart stopped selling so-called assault rifles.

DAVIS: Walmart, when they did that, said it was because customer demand for these guns was down, and I hope that’s the case, because if that’s the case that’s a very good sign for the country. But theoretically if customer demand came back for some reason, Walmart could still do something different, because they didn’t base their decision on principles of ethics.

SEVERSON: Michael Hammond says the reason Episcopal churches like Trinity have been losing members is because of their social activism.

HAMMOND: My point is that there are churches doing very well in America that are meeting in auditoriums, and by and large the commonality in those churches is that they talk about, more specifically than Trinity does, about God rather than about the most recent liberal cause.

LUPFER: If you read the gospels, you see that Jesus was constantly being accused of talking about temporal issues rather than spiritual issues, and he made no distinction between spiritual and temporal. In fact, we say that a good preacher prepares sermons with a Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other, and that we need to be engaged in the language of our culture outside our churchgoers.

SEVERSON: Hammond warns that Trinity’s victory could spell trouble for corporations, even countries.

HAMMOND: The effort to get Walmart to stop selling certain types of firearms is part of a larger phenomenon in which, for instance, universities are considering using their very small shareholdership in very large corporations to get the corporations to divest from Israel, or that sort of thing.

SEVERSON: These investors for corporate responsibility seem undeterred, if anything more determined. Reverend Schilling says it takes a lot of tenacity to turn a corporation around, especially those that turn a blind eye to human rights violations.

SCHILLING: You have to have some audacity, and you have to have some hope, and you have to have some faith.

SEVERSON: While Walmart declined to comment to us for this report, the company has responded in the past to pressure over what it sells. It stopped stocking handguns 20 years ago, and after 2015’s deadly church shootings in Charleston, South Carolina, it removed items displaying the Confederate flag from its stores.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Lucky Severson reporting.