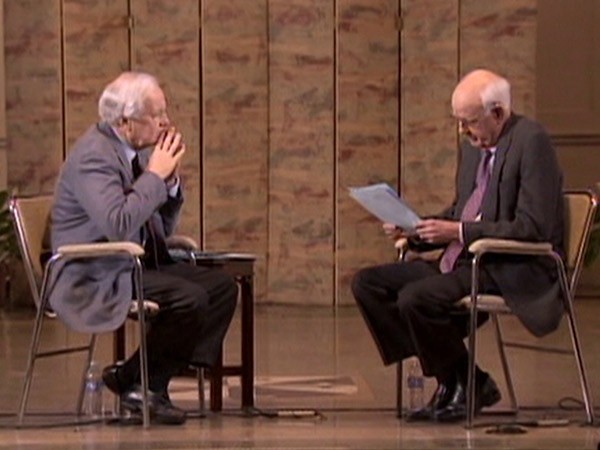

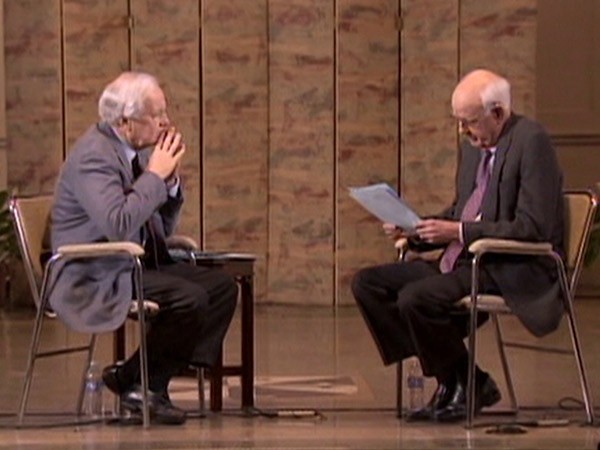

JUDITH VALENTE, correspondent: The farm fields and rolling knobs of central Kentucky: This is the landscape that inspires Wendell Berry’s work as an award-winning poet, fiction writer, and essayist. In one of his rare TV interviews Berry, seen here in 2013 with Bill Moyers, read his poem “The Peace of Wild Things”:

WENDELL BERRY: “When despair for the world grows in me … I go and lie down where the wood drake / rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.”

WENDELL BERRY: “When despair for the world grows in me … I go and lie down where the wood drake / rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.”

VALENTE: The Berry family has lived in these parts for nine generations. While pursuing a prolific writing career Berry, like his ancestors, continued caring for this land as a farmer. The 81-year-old writer and his family now seek to pass on their farming legacy to a new generation. They’ve chosen to do that not through any large university agricultural program, but at this small Catholic liberal arts college about an hour’s drive from Louisville, run by the Dominican Sisters of Peace.

SISTER CLAIRE MCGOWN (St. Catharine College): It’s probably the most unlikely place that the Berry Farming Program could have ended up.

VALENTE: Why is that?

SISTER MCGOWAN: Well, because we’re so small, because we’re so rural, because we’re not famous. But those are the characteristics that the Berry family appreciates and promotes.

VALENTE: The Dominican sisters have been part of this community since 1822, teaching—and farming—on their own 550-acre stretch of land. That meant a lot to Wendell Berry’s daughter, Mary.

MARY BERRY (Executive Director, Berry Center): Their first question to me was not about my father’s reputation and how it might serve their desire to raise funds.

SISTER MCGOWN: Well, the Dominican Sisters of Peace work out of four pillars: prayer, study, community, and ministry.

MARY BERRY: The first question at St. Catharine’s to me was how does your work fit with the four pillars of the Dominican life?

VALENTE: Berry, whose writings often explore the connection between the natural world and the human spirit, proved a good fit for the sisters, too.

Wendell Berry: “I come into the presence of still water. And, I feel above me the day blind stars waiting with their light. For a time I rest in the grace of the world and am free.”

SISTER MCGOWAN: Wendell Berry is a deeply soulful man. He lives his life out of deep spiritual convictions and has a love for people, particularly simple people who are trying to build a relationship with the natural world.

SISTER MCGOWAN: Wendell Berry is a deeply soulful man. He lives his life out of deep spiritual convictions and has a love for people, particularly simple people who are trying to build a relationship with the natural world.

VALENTE: The Berry Farming Program at St. Catharine offers a unique interdisciplinary approach to agriculture combining field work with philosophy, studies in agricultural science, and agribusiness with classes on literature, history, and culture. Leah Bayens is the program’s coordinator.

LEAH BAYENS, PhD (Chair, Earth Studies Department): When Wendell says things like “you can’t take the culture out of agriculture,” ultimately I think what he means is that you can’t minimize it into an equation or minimize it into one particular scientific study.

VALENTE: For Berry, the heart of agriculture springs from a spiritual kinship with the land.

Wendell Berry: “We have the world to live in and the use of it to live from on the condition that we will take good care of it.”

BAYENS: It makes an ethical and spiritual relationship to land stewardship the center point, not something out on the periphery.

BAYENS: It makes an ethical and spiritual relationship to land stewardship the center point, not something out on the periphery.

VALENTE: It’s a belief about the land Berry laid out in a 2012 lecture called “It All Turns on Affection” that he delivered after receiving a National Endowment for the Humanities Medal for his lifetime of work.

BAYENS: To have a sense of affection for one another and for the nonliving beings, that’s what we’re trying to instill as a goal for our students.

VALENTE: That’s why practices in soil stewardship are a major part of the Berry program, as are classes like this one in eco-spirituality, taught by religious studies professor Matt Branstetter.

PROFESSOR MATT BRANSTETTER (Chair, Religious Studies Department): He’s really great at bringing out the spirituality of what would otherwise seem like very simple, mundane everyday tasks, but looked upon with the right attitude they’re kind of living mysticism.

Wendell Berry: I still consider myself a person who takes the gospels very seriously. A lot of my writing, when it hasn’t been in defense of precious things, has been a giving thanks for precious things.

VALENTE: Mary Berry says the trend over the past century toward ever bigger industrial farms has got to change.

MARY BERRY: If anything was working very well we would have more people farming. We have three-quarters of one percent of the population farming now.

MARY BERRY: If anything was working very well we would have more people farming. We have three-quarters of one percent of the population farming now.

VALENTE: The Berrys hope to encourage more young people to farm on mid-sized parcels of land that produce locally- grown products for local markets—farms that emphasize soil conservation and depend less on chemical fertilizers and herbicides.

MARY BERRY: I heard Daddy say recently that big agriculture, industrial agriculture is in its death throes. It’s brain dead, and it’s just thrashing around now. I think he’s right.

VALENTE: In a part of the country where farmers once depended for their income on growing tobacco, a crop in severe decline, Berry program students are researching ways farmers can diversify and are planting new crops that may do well in Kentucky’s unique soil. On this 15-acre research farm, students are participating in a government-sponsored program that grows a type of hemp used in making clothing fiber. Shawn Lucas teaches soil science.

PROFESSOR SHAWN LUCAS, PhD (Assistant Professor, Sustainable Agriculture): The soil is not just dirt. It’s minerals, organic materials, living roots, living micro-organisms, and the more diversity you can get into that system the healthier it’s going to be.

VALENTE: The farming program has grown from just one student two years ago to 25 now. The students come from urban areas, from farm families, and from as far off as India and Nepal. This student plans to return eventually to his family’s grain farm in West Africa.

SIE TIOYE (Student): I think the most attractive thing about this farming program is that it teaches you how to make a productive farming system, to create a productive farming system using very basic techniques.

SIE TIOYE (Student): I think the most attractive thing about this farming program is that it teaches you how to make a productive farming system, to create a productive farming system using very basic techniques.

RACHEL MENDOZA (Student): I’m particularly attracted to urban agriculture and meeting the needs of under-met people in our urban communities.

SHELBY FLOYD (Student): He writes in a way that you’re sitting on the front porch at the farm with him.

VALENTE: Before enrolling in the program, many of the students had never read Berry’s famous poems, stories, and essays on farming, but they can now quote chapter and verse.

WINNIE CHEUVRONT (Student): I always love this one quote: “What I stand for is what I stand on.” And to me that means a lot, because we all walk on this earth, and why are we not taking care of it? And that’s something he tries to convey in his writings so that we all can get a passion for the earth and for what we do in everyday life.

VALENTE: Mary Berry says she’s thrilled many of the students want to farm in communities where they were raised. She half-jokingly says the farming center offers degrees in “homecoming.”

MARY BERRY: We need to go someplace and dig in. So the concept of homecoming, I think, is simply to take root someplace, care about a place not just for a short amount of time, but forever.

MARY BERRY: We need to go someplace and dig in. So the concept of homecoming, I think, is simply to take root someplace, care about a place not just for a short amount of time, but forever.

VALENTE: The Berry family says the program is ultimately trying to recreate the kind of supportive agricultural community that it benefited from through generations of farming.

MARY BERRY: We were surrounded by neighbors and friends and family who had known the farm we bought all their lives, so they understood. They knew the mistakes we might make. They’d seen them made. They could advise us. They could give us what no college program could give us.

VALENTE: It is a line of remembering Mary Berry says her family doesn’t want to see lost, and one reflected in this poem of her father’s on hope:

Wendell Berry: “Find your hope then on the ground under your feet. / Your hope of heaven. Let it rest on the ground / underfoot.”

VALENTE: For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Judy Valente in St. Catharine, Kentucky.

WENDELL BERRY: “When despair for the world grows in me … I go and lie down where the wood drake / rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.”

WENDELL BERRY: “When despair for the world grows in me … I go and lie down where the wood drake / rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.”  SISTER MCGOWAN: Wendell Berry is a deeply soulful man. He lives his life out of deep spiritual convictions and has a love for people, particularly simple people who are trying to build a relationship with the natural world.

SISTER MCGOWAN: Wendell Berry is a deeply soulful man. He lives his life out of deep spiritual convictions and has a love for people, particularly simple people who are trying to build a relationship with the natural world. BAYENS: It makes an ethical and spiritual relationship to land stewardship the center point, not something out on the periphery.

BAYENS: It makes an ethical and spiritual relationship to land stewardship the center point, not something out on the periphery. MARY BERRY: If anything was working very well we would have more people farming. We have three-quarters of one percent of the population farming now.

MARY BERRY: If anything was working very well we would have more people farming. We have three-quarters of one percent of the population farming now. SIE TIOYE (Student): I think the most attractive thing about this farming program is that it teaches you how to make a productive farming system, to create a productive farming system using very basic techniques.

SIE TIOYE (Student): I think the most attractive thing about this farming program is that it teaches you how to make a productive farming system, to create a productive farming system using very basic techniques. MARY BERRY: We need to go someplace and dig in. So the concept of homecoming, I think, is simply to take root someplace, care about a place not just for a short amount of time, but forever.

MARY BERRY: We need to go someplace and dig in. So the concept of homecoming, I think, is simply to take root someplace, care about a place not just for a short amount of time, but forever.