DAN LOTHIAN, correspondent: Slava Vakarchuk is Ukraine's biggest rock star. He's the front man of the popular band Okean Elzy. Raised in the Orthodox tradition, the self-described Christian jumped onto the stage as a teenager, and all these years later Vakarchuk has become an institution—not only because of his music, but his social and cultural activism. These days his surroundings are a bit quieter on the campus of Yale University, where he's a World Fellow taking classes at the Divinity School. Yes—a rock star in seminary.

SLAVA VAKARCHUK: I'm just an inquisitive person. I like studying. I like learning new things. And I never had anything from some theologians or taking classes in theology or things like that. So I was very curious, and I'm very happy to be here.

SLAVA VAKARCHUK: I'm just an inquisitive person. I like studying. I like learning new things. And I never had anything from some theologians or taking classes in theology or things like that. So I was very curious, and I'm very happy to be here.

LOTHIAN: And it seems Vakarchuk isn’t the only one “happy to be here.” He’s part of a growing trend at divinity schools across the country where students are enrolling in similar programs simply to study theology with no intention of ever becoming ordained as clergy.

VAKARCHUK: You know, when you go to Yale University or to the other universities to study history it's not because you want to become a historian or teach history school. Sometimes you want to know history because knowing history enriches you, broadens up your mind, horizons, and makes you a wiser person. The same thing with theology.

LOTHIAN: And this desire to broaden the mind is also attracting other students from far-away places with surprising belief systems.

PROFESSOR MIROSLAV VOLF: One of the students, for instance, told us that she had the need to think about those things. She herself is an atheist from India.

PROFESSOR MIROSLAV VOLF: One of the students, for instance, told us that she had the need to think about those things. She herself is an atheist from India.

LOTHIAN: She's an atheist from India—

VOLF:—who came as a Yale student and who took our class. We welcome atheists. We welcome theists. We welcome religious people who aren't theist. Everybody's welcomed. Indeed, we try to have a very diverse group of folks. What she didn't know, or didn't see, or didn't experience before is that she would have permission to think in academic terms about the great question of life. For her that was a revelation.

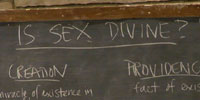

LOTHIAN: Professor Miroslav Volf, a prominent theologian and head of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture, is teaching several courses at Yale that give students permission to think in an academic environment about the great questions of life. "Christ and the Good Life" and "A Life Worth Living" are drawing students with diverse interests that all have similar intentions.

VOLF: What motivated these courses is the sense that in culture today we tend to spend a lot of time thinking about how to succeed in one or the other endeavor that we undertake, but we tend to spend very little time thinking about how do I succeed as a human being.

LOTHIAN: Teaching how to succeed as a human being also includes exploring historical, philosophical and sociological lessons. The course has deepened student Taylor Bolton's understanding of life.

LOTHIAN: Teaching how to succeed as a human being also includes exploring historical, philosophical and sociological lessons. The course has deepened student Taylor Bolton's understanding of life.

TAYLOR BOLTON: I also believe that nothing is completely academic. Nothing is completely social, and there's a spiritual component, I think, to everything.

LOTHIAN: And the spiritual component seems to be an element students are seeking to explore in a deeper way. The study of religion offers a different but welcome foundation.

VAKARCHUK: It's not that I need to be converted or not that I need to get a job after that. It's something that, you know, I want to go deeper. This is it.

LOTHIAN: Whether it's a rock star or a business major, the elements of spirituality are being studied as the basis for living a good life. At Harvard University, Gregory Epstein, who is the Humanist chaplain and describes himself as an agnostic and atheist, figured out a long time ago that there was more to religion than religion. He’s been recruiting others, including non-believers, to the divinity school.

GREGORY EPSTEIN: A lot of what religion is about on the day-to-day level for people is exploring what's most meaningful to people, exploring community and figuring out how to come together with a community to make the world a better place. That was the topic I wanted to spend the rest of my life learning about.

LOTHIAN: And coming together is exactly what Harvard Divinity School student Christopher Raiche is hoping to achieve. He founded a group called White People against Racism to fight social injustice. Although he describes himself as “not very theistic,” he uses the fundamentals of religion to try to change some of the attitudes that perpetuate racism.

LOTHIAN: And coming together is exactly what Harvard Divinity School student Christopher Raiche is hoping to achieve. He founded a group called White People against Racism to fight social injustice. Although he describes himself as “not very theistic,” he uses the fundamentals of religion to try to change some of the attitudes that perpetuate racism.

CHRISTOPHER RAICHE: The ways that religions have developed practices, liturgies and methods for cultivating the heart, for opening us up to the curious quality of being here as a human and how to live that beautifully, how to live that deeply—that is just to me the real treasure. I'm just seeing and appreciating how that is lived so deeply by so many different people of different faiths.

LOTHIAN: Raiche’s group meets at the Humanist Hub, an off-campus place Epstein created to bring people together to connect with others who are interested in making the world a better place. They meet on Sundays. They read poems, sing songs and listen to guest speakers. In fact, it even feels a little like, well, church. But it isn’t.

EPSTEIN: I'm finding more and more that nonreligious people are looking around and saying, wait a second. I'm not religious, but I do miss the idea of community that I would get if I were religious. I wish I could find some kind of nonreligious alternative to that kind of community.

LOTHIAN: As Raiche sees it, the Humanist Hub is one compelling answer.

RAICHE: It's all aiming toward how to be a more intimate participant in civic life and in relationship with the world, doing it through economics, science, art—whatever if might be.

RAICHE: It's all aiming toward how to be a more intimate participant in civic life and in relationship with the world, doing it through economics, science, art—whatever if might be.

LOTHIAN: According to the Pew Research Center, the number of people who consider themselves to be religiously unaffiliated, including atheists and agnostics, is on the rise—about a fifth of the US population. Some say they are turned off by too much politics and too many rules in organized religion. Others say faith and facts don't add up. But those numbers don't mean non-believers can’t find value in religion, its traditions and even the teachings of Jesus. This is a topic author Tom Krattenmaker explores in his new book, Confessions of a Secular Jesus Follower.

TOM KRATTENMAKER: I've been sensing and hearing from other people who are not part of organized religion anymore, but who really admire Jesus. They're not quite sure if Jesus is available to them. They're not quite sure if it's legit for them to engage with Jesus as a nonreligious person. So I wanted to make Jesus available to people like that, including me. I wanted to articulate what it is about Jesus that appeals to me and makes me inspired by Jesus.

LOTHIAN: And what exactly does Jesus offer non-believers, besides salvation?

KRATTENMAKER: There's ethical instruction. There's inspiration. There are these very rich stories that help us reorient the way we see the world and the way we live our lives. It's amazing that these stories from 2,000 years ago are so salient and helpful today.

KRATTENMAKER: There's ethical instruction. There's inspiration. There are these very rich stories that help us reorient the way we see the world and the way we live our lives. It's amazing that these stories from 2,000 years ago are so salient and helpful today.

LOTHIAN: Those sentiments are echoed by Volf back in the classroom at Yale. And while all views are welcomed and respected, he does not waver on his own beliefs.

VOLF: From the get-go in the class it's clear that I am a Christian. I believe that Christian faith is true. I would be happy if a person would embrace this, but my goal is not to evangelize them, to turn them into Christians. My goal as a teacher is to referee their own search, where they take seriously the question of truth.

LOTHIAN: And students like Vakarchuk, curious about theology, and other believers seeking to enrich their lives as they launch into secular careers, say divinity school will have a lasting influence.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I'm Dan Lothian in Boston.

SLAVA VAKARCHUK: I'm just an inquisitive person. I like studying. I like learning new things. And I never had anything from some theologians or taking classes in theology or things like that. So I was very curious, and I'm very happy to be here.

SLAVA VAKARCHUK: I'm just an inquisitive person. I like studying. I like learning new things. And I never had anything from some theologians or taking classes in theology or things like that. So I was very curious, and I'm very happy to be here. PROFESSOR MIROSLAV VOLF: One of the students, for instance, told us that she had the need to think about those things. She herself is an atheist from India.

PROFESSOR MIROSLAV VOLF: One of the students, for instance, told us that she had the need to think about those things. She herself is an atheist from India. LOTHIAN: Teaching how to succeed as a human being also includes exploring historical, philosophical and sociological lessons. The course has deepened student Taylor Bolton's understanding of life.

LOTHIAN: Teaching how to succeed as a human being also includes exploring historical, philosophical and sociological lessons. The course has deepened student Taylor Bolton's understanding of life. LOTHIAN: And coming together is exactly what Harvard Divinity School student Christopher Raiche is hoping to achieve. He founded a group called White People against Racism to fight social injustice. Although he describes himself as “not very theistic,” he uses the fundamentals of religion to try to change some of the attitudes that perpetuate racism.

LOTHIAN: And coming together is exactly what Harvard Divinity School student Christopher Raiche is hoping to achieve. He founded a group called White People against Racism to fight social injustice. Although he describes himself as “not very theistic,” he uses the fundamentals of religion to try to change some of the attitudes that perpetuate racism. RAICHE: It's all aiming toward how to be a more intimate participant in civic life and in relationship with the world, doing it through economics, science, art—whatever if might be.

RAICHE: It's all aiming toward how to be a more intimate participant in civic life and in relationship with the world, doing it through economics, science, art—whatever if might be. KRATTENMAKER: There's ethical instruction. There's inspiration. There are these very rich stories that help us reorient the way we see the world and the way we live our lives. It's amazing that these stories from 2,000 years ago are so salient and helpful today.

KRATTENMAKER: There's ethical instruction. There's inspiration. There are these very rich stories that help us reorient the way we see the world and the way we live our lives. It's amazing that these stories from 2,000 years ago are so salient and helpful today.