In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

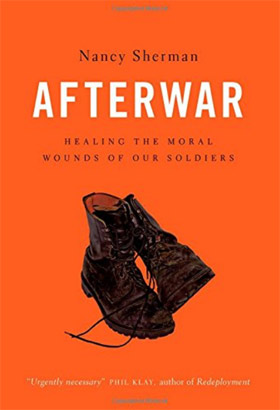

Healing Moral Wounds of War

In her book Afterwar: Healing the Moral Wounds of Our Soldiers, Georgetown University philosophy professor Nancy Sherman argues that many of the 2.6 million U.S. service members returning from our wars in Afghanistan and Iraq suffer from complex moral injuries that are more than post-traumatic stress and that have to do with feelings of guilt, anger, and “the shame of falling short of your lofty military ideals.” Citizens have “a sacred obligation,” says Sherman, to morally engage with those who have fought in our name and who feel moral responsibility for traumatic incidents they experienced. Managing editor Kim Lawton interviews Sherman about the moral aftermath of war and visits a former Marine and his wife to talk about the healing that comes through listening, trust, hope, and moral understanding.

Read an excerpt from Afterwar: Healing the Moral Wounds of Our Soldiers by Nancy Sherman (Oxford University Press, 2015):

Many who return from war are dogged by profound disappointment in themselves and the sense that they have fallen short of ideals of what it is to be a good solider. Sometimes the disappointment stems not from wrongdoing or evil, but from an over-idealized sense of good soldiering, or an intolerance for good and bad luck in war. In a related way, some may feel (subjective) guilt that doesn’t track culpability or wrongdoing. In some of these cases, there may be causal but not moral responsibility at work, such as when an individual is the proximate cause of a nonculpable accident. In other cases, merely surviving when a buddy doesn’t, without any sense of being the agent or cause of that buddy’s death, unleashes deep guilt and despondency.

Hope in the face of evil is another matter, either when one is the victim of evil or when its perpetrator. There is no shortage of evil in going to war and killing and maiming for a cause that may not be just or at least is imprudent, as many in the public increasingly regard the wars in Afghanistan, and—especially—Iraq. …This may speak to all sorts of issues, including an enlisted military and not a drafted one, a conservative-leaning military, a military that swelled in the wake of a patriotic surge after 9/11, or wars that have wound down only to be reignited. I suspect there will be far deeper disillusionment as the experiences of investing $2 trillion and too many lives in Iraq and Afghanistan leave little lasting impact in those regions.

The experience of some of the Marine veterans of the bloody Fallujah invasion of the Anbar region of Iraq in November 2004 may be indicative here. The battle that wrested the insurgent-held city was fierce and costly, and for the Corps a defining moment of the twelve years of war in Iraq and Afghanistan, with nearly 100 Marines killed and hundreds wounded. When the city fell back to insurgent Sunni forces with Al Qaeda links in January 2014, shock waves of disbelief ran viral through the close-knit Marine community who fought in that battle. Wirth the fall came a lost sense of the mission and what they cook themselves to accomplish. As Kael Weston, a State Department political adviser who worked closely with Marines in Fallujah and later Afghanistan put it, “This is just the beginning of the reckoning and accounting.” The reckoning will come, and with it the shifting grounds of hope or despair. This is a future story to be told for these veterans and for many others who have served in these wars.

Early on in the philosophical record, Aristotle invokes that image of a friend as “another self,” a “mirror,” not for narcissistic reflection, he insists, but for self-knowledge “when we wish to know our own characters…and direct study of ourselves” is near impossible. The background assumption in Aristotle’s claims is that we are not empty vessels for others’ aspirations, but we are aspirants who can’t do without others’ support, trust, and compassionate critique in articulating how to live well and then trying to live that life.

For a returning veteran, recognizing that another has invested hope in you can be profoundly transformative. It can nourish hope in oneself and sustain hope for projects that rekindle a sense of meaning and purpose after war. It is an important moment in healing.