Choir singing: “Go make a dff'rence, we can make a diff'rence. Go make a diff'rence in the world...”

DEBORAH POTTER, correspondent: Born and raised Catholic, Mary Margaret O'Connor thought her marriage would be for life. When she divorced, going to Mass wasn't easy.

MARY MARGARET O'CONNOR (Parishioner, St. James Church, Arlington Heights, Illinois): You walk into a church, and it’s loaded with families. So if you’re divorced and you’re alone, you walk into this and there’s just so many reminders of what you once had, but don’t have any more.

POTTER: Even so, she kept going. But some of her divorced friends stayed away.

O'CONNOR: So I started saying, “all right,” to my friends who were divorced Catholics, “first word that pops into your head, you’re a divorced Catholic: Excommunicated.” “What? Excommunicated? Oh, come on, we are not excommunicated.” “Yeah, excommunicated.”

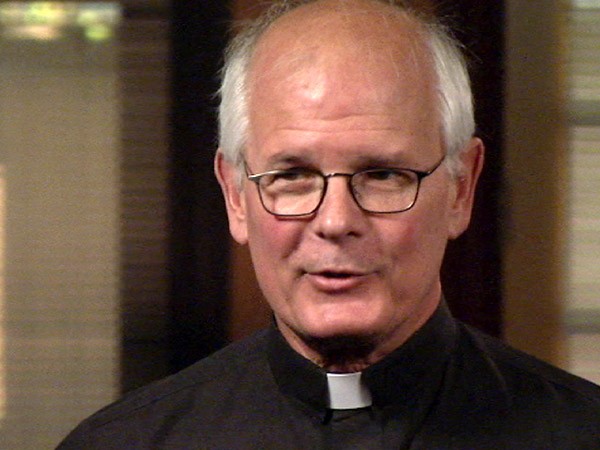

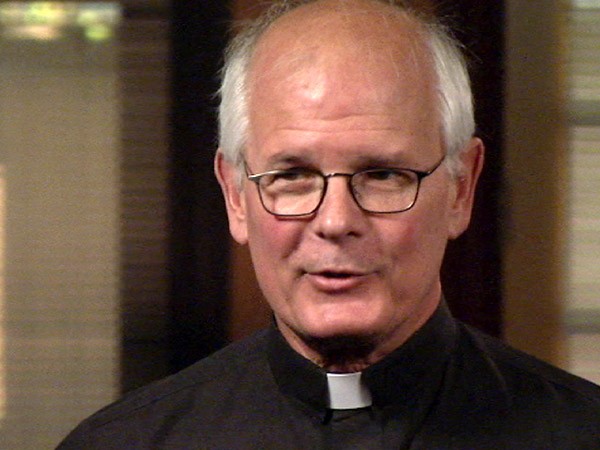

FR. JAMES HALSTEAD (DePaul University, Chicago): The amount of misinformation about marriage in the Catholic tradition boggles my imagination.

POTTER: Father James Halstead teaches a course on marriage at DePaul University in Chicago. Divorced Catholics, he says, are not excommunicated—deprived of all sacraments—and they haven't been for more than a century. But the perception lingers, largely because the church teaches that marriage is a symbol of Christ's relationship with the church and cannot be broken.

FR. HALSTEAD: The Roman Catholic tradition is, “No, you’re participating in something bigger than you are, that is, a natural institution created by God in the beginning, sanctified by Christ, a sacrament, and you’re part of it. You didn’t invent it, and it’s not yours to make whatever you want.”

That’s a colorful conversation when you do pre-marital counseling!

POTTER: Any divorced Christian wanting to remarry in the Catholic Church must have the previous marriage annulled—decreed invalid by church authorities. If they remarry without an annulment, they're considered to have committed the mortal sin of adultery and are banned from taking communion. How many American Catholics are affected? Researchers at Georgetown University provided the numbers. More than one in four Catholic marriages in this country end in divorce. That’s a lower rate than the general population, but it’s still 11 million people. An annulment would allow them to remarry and remain full members of the church, but only 15 percent of divorced American Catholics have gone to the trouble of getting one.

DODIE CARNEY (Parishioner, Holy Family Church, Inverness, Illinois): You go through all the pain that you went through while you were going through a divorce.

POTTER: Dodie Carney had her marriage annulled seven years after her civil divorce. She was never denied communion, but she had divorced friends who were.

CARNEY: I think the church was concerned more about legalism and—instead of compassion for the individual. And when you’re going through a hard time the best thing you can have is Jesus inside of you...and receiving communion. That’s when you need it the most is when you’re hurting.

POTTER: American Catholics have long been out of step with the Vatican on major family issues. Almost two-thirds of Catholics in the United States believe couples living together should be allowed to receive communion, according to a recent survey, and three-quarters want the church to approve the use of contraception.

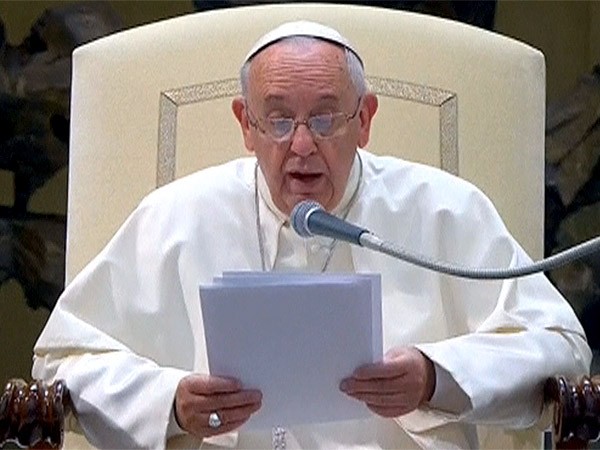

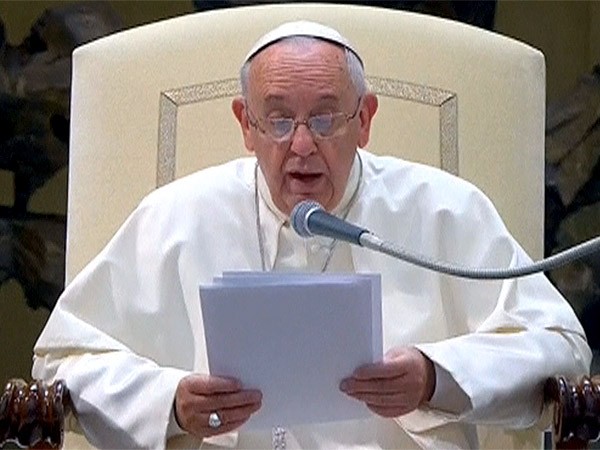

Some Catholics who want the church to change its stance on family issues have taken heart from recent actions and comments by Pope Francis.

POPE FRANCIS: (subtitled) “The baptized who have established a new union after the failure of sacramental marriage, in actual fact, are not excommunicated. They are not excommunicated.”

POTTER: He's made annulments simpler and quicker. He's called divorce sometimes "morally necessary" and said abortion can be forgiven. And, of homosexuality, the pope asked, "Who am I to judge?"

Luis Garcia: “That’s how the connection was made.”

Friend: “Oh...”

POTTER: Luis Garcia grew up Catholic and studied to become a priest, but he did feel judged as a gay man and walked away from the Catholic Church 30 years ago.

LUIS GARCIA (Church of the Atonement, Chicago): Bottom line is I could never show up to church with a boyfriend, I could never imagine having my union recognized. I had to keep details of who I was separate from my spiritual life. And as someone who has served in the church all of his life, that made me feel dishonest.

POTTER: Like many former Catholics, Garcia found a new church home—in his case, an Episcopal church where the liturgy feels familiar and where same-sex couples can marry.

GARCIA: Easily 40 percent of the members of this congregation started their faith journey and their life journey in the Roman Catholic Church and now worship here, so it’s not just me. It’s a lot of us.

POTTER: According to a recent survey, only one-in-ten Catholics who leave the church ever returns.

O'CONNOR: They would rather go to Willow Creek or another nondenominational church, because those churches have really helped them rebuild their lives, where the Catholic Church has not helped to rebuild anyone’s life. It’s hurt people more than it’s helped.

POTTER: O'Connor has found an ally in her parish priest, who's helping her organize a new ministry for divorced Catholics.

FR. MATT FOLEY (St. James Church, Arlington Heights, Illinois): We need to bring people back into the communion with the church and around the Lord’s Table, and I think that would be beneficial, not just for us as a parish, but for us as a church in the world.

“Behold the lamb of God. Behold him who takes away the sins of the world...”

DR. SUSAN ROSS (Department of Theology, Loyola University, Chicago): On the one hand, you know, in a church where there are declining numbers of people, why not open the doors and be as welcoming as possible to people who really want to be a part of this community? And yet on the other hand, if you allow for wiggle—more than wiggle room, if you allow for some changes in practice, what does that do?

Dr. Ross: “Let’s stick with this for a minute.”

Student: “Yeah, good.”

Dr. Ross: “Because this is significant epistemologically. So what does it mean to be in a particular standpoint?”

POTTER: Susan Ross chairs the theology department at Loyola University, Chicago.

DR. ROSS: The church is in a sense caught between its own rock and its own hard place. Justice on the one hand requires that the canonical requirements for marriage be followed. Mercy on the other hand says wait a minute, these people want to be part of a worshipping community; they want to participate fully.

POTTER: Pope Francis has urged a pastoral response to remarried Catholics and gays, but he hasn't spelled out what that means.

FR. HALSTEAD: He knows what can change politically. He knows what can change doctrinally, what can change canonically, and he’s a rather shrewd political guy. I have no idea what’s going on in his head, and I think he likes it that way.

O'CONNOR: I pray for him every day, because it’s very brave for him to come out and say we must do more to welcome back divorced Catholics and that divorce is sometimes morally necessary. So he is the first pope that’s ever said that. My prayer is that everyone will listen to him. Just because he says it doesn’t mean that you’ll have the archbishops and the cardinals following suit.

POTTER: A bishops' meeting next month will decide whether to recommend changes in the church's positions on family issues. Conservative and liberal bishops already are publicly at odds over what to do. And the Gospel reading for opening day? One of the clearest statements in the New Testament forbidding divorce.

“Therefore what God has joined together, no human being must separate.” (Mark 10:9)

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I'm Deborah Potter in Chicago.