FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: Jaipur is one of India's top tourist destinations but not far from its architectural landmarks is a far more modest one that draws a whole different kind of visitor. They come—literally—on hands and knees to an organization commonly known as Jaipur Foot.

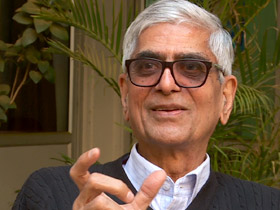

DEVENDRA RAJ MEHTA: Now every year we are fitting anything between 23 to 25,000 limbs.

DE SAM LAZARO: D.R. Mehta began offering artificial limbs and other services to physically disabled people nearly 40 years ago, after suffering a broken leg that nearly had to be amputated after a car accident.

A 74-year-old former bank regulator, Mehta says the experience sensitized him to the plight of millions in this country who lack good orthopedic care—desperate people like Zareena, a widow who said she is reduced to panhandling to support her two children.

MEHTA: Where are you coming from?

ZAREENA: Bombay.

MEHTA: Bombay...a long, long way. What do you need?

ZAREENA: A cycle.

MEHTA: She wants a hand pedaled tricycle.

ZAREENA: You are the answer to my prayer...

DE SAM LAZARO: She's one of at least 5.5 million people in India with so-called locomotor disabilities—caused in her case by childhood polio. Others suffer congenital conditions. But the most frequent customers are amputees, victims of rail or road accidents.

They are served free of charge. The organization runs on government and foundation grants and its costs—for a typical lower limb, for example—are minuscule by Western standards.

MEHTA: Now it's fifty dollars.

DE SAM LAZARO: Here’s a comparison: In the United States, a prosthesis like this would typically range in price from $8,000 to $12,000. It would be made of metal, aluminum, possibly carbon fiber. Whereas in Jaipur, the key ingredient is PVC piping more commonly used to irrigate farms. And this is the key to a $50 artificial leg. They're made in simple molding facilities, cut and trimmed by hand. About a third of the workers themselves have Jaipur limbs. They are made physically whole again, Mehta said, as he asked these amputees to show us by sprinting.

MEHTA: They can go and work back in their field, factory, or shop, earn their living. They start earning again. They acquire social respect, and they acquire self-confidence again.

DE SAM LAZARO: Social respect and self-confidence are critical in a land where disability carries stigma—seen as bad karma, punishment for one's misdeeds in a previous life, says Pooja Mukul, an orthopedics specialist at Jaipur.

DR. POOJA MUKUL: Disability in the West is seen as pure disability. You lose a limb, you met with an accident, or you went to war or whatever, but here in India, we associate everything with karma. People don’t want to be identified as disabled. They want to look normal. They don’t want people to know they’ve lost a limb.

DE SAM LAZARO: Dr. Mukul says that's especially challenging in amputations above the knee.

DR. MUKUL: So much so that it's better to lose both the limbs below the knee than to lose one leg above the knee. And the knee has been the weakest link in prosthetic componentry in the developing world. We’ve had very simple knee joints which are single axis, which are more like door hinges, and we’ve been using them largely because of the simplicity, low cost and also non-availability of any other options.

DE SAM LAZARO: Dr. Mukul is leading the effort to develop better options, partnering with MIT and Stanford University. With animation software typically used in movies, they've conducted so-called "gait analysis" to inform the design.

DR. MUKUL: So this is the first prototype or version one of the polycentric knee that we developed in collaboration with Stanford.

DE SAM LAZARO: Trials over the past five years with hundreds of patients in India and several other developing nations helped refine the new Jaipur knee...

DR. MUKUL: This had this clicking sound.

DE SAM LAZARO: ...removing, for example, a clicking sound from version one.

DR. MUKUL: Our patients don’t want to hear clicks. And they don't want to be labeled as disabled. They don’t want a sound preceding their entry into an area. So then we got a bumper put in here, and now it is silent. Also the geometry—this is very squarish, doesn’t match the human geometry in any way. This one is more like a knee.

DE SAM LAZARO: The new Jaipur knee, specifically tailored for the developing world, will be ready for mass production later this year.

MEHTA: We have tried to marry service with science. That’s our motto.

DE SAM LAZARO: That motto was learned early from his mother, he says.

MEHTA: She felt that, in terms of religion, to help others is something that is very good karma.

DE SAM LAZARO: In a country where karma and religious piety are important, the Jaipur Foot project goes out of its way to display icons from all of India's major religions, a symbol that everyone is welcome.

MEHTA: This is Mahaveer.

DE SAM LAZARO: Mehta himself is a follower of a Jainism, whose ancient guru Mahaveer preached among other things that all life and life forms are equal.

MEHTA: This is Ganesha. This is Buddha.

DE SAM LAZARO: In the modern times, he says, that means restoring not just people's mobility but also their dignity. Many who come are also provided means to start a microenterprise, for example, a sewing machine or more commonly simple kits to start a roadside tea stall.

MEHTA: Everybody knows how to make tea. And everybody drinks tea.

DE SAM LAZARO: Zareena was getting ready to return home.

ZAREENA: Having this cycle gives me some freedom now.

DE SAM LAZARO: The tricycle promises relief from severe stress on her arms and legs, she said.

ZAREENA: My neighbors have told me that I can open a small shop, selling little candies, smokes, and matches. I should be able to put these children in school. That’s all I want.

DE SAM LAZARO: For the first time in a long while, she says, the future they ride into will carry hope for her children.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Jaipur, India.