JUDY VALENTE, correspondent: A Saturday morning at the Catholic Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation on Chicago’s South Side. Mothers from across the city gather for a healing circle, led by Sister Donna Liette.

JUDY VALENTE, correspondent: A Saturday morning at the Catholic Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation on Chicago’s South Side. Mothers from across the city gather for a healing circle, led by Sister Donna Liette.

Sister Donna Liette: We have Damon’s picture there and Jimmy’s, two young boys in the neighborhood whose lives were taken by violence.

VALENTE: Most of these women here have children who were either killed or are in prison. They begin with a poem titled “Stop”:

“Stop the killing, the drug dealing, the gang banging / Stop the tears falling from our mother’s eyes. Stop the pain in our mother’s hearts.”

VALENTE: And then each mother tells her story:

VALENTE: And then each mother tells her story:

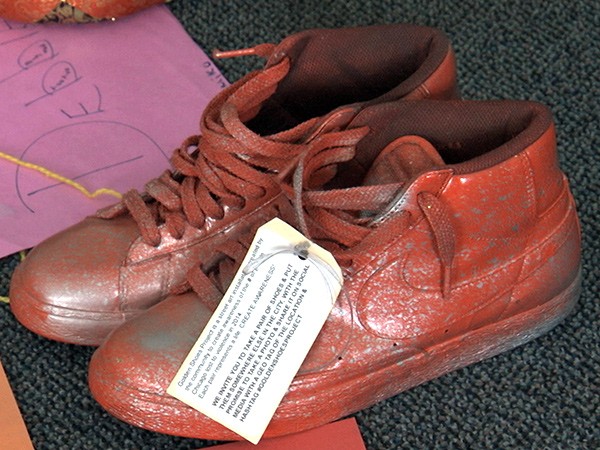

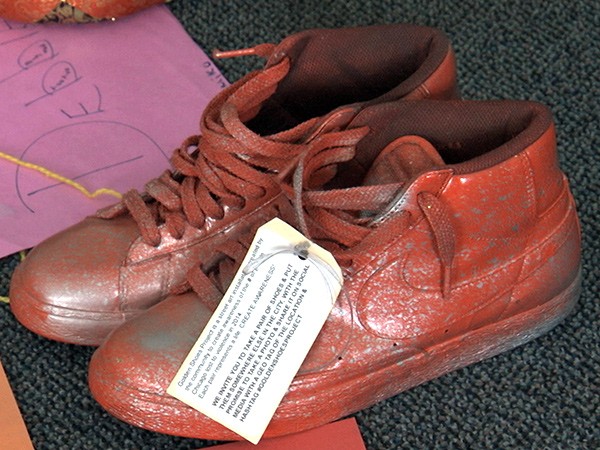

“These are the shoes my son wore. He was a victim of gun violence in the Kenwood community two and a half years ago.”

“They took my son’s life for no reason. He wasn’t a gang banger.”

“My son is serving life in prison for a crime he committed when he was 15, He’s now 36. I’ve seen gun violence from the other side.”

VALENTE: The Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation also offers support to the other victims of gun violence—the survivors.

“I came to the circle hurt, I came angry. It’s like my nephew didn’t have a chance. He was 19, he had just celebrated his birthday. I don’t know how people go through this without a faith in God.”

VALENTE: Father Dave Kelly is the center’s director. He says the center tries to be a place of what he calls “radical hospitality.”

FATHER DAVE KELLY (Director, Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation): Accompaniment is walking alongside. It’s very much a biblical kind of thing of just accompanying someone on the journey. Being there on that journey. Not necessarily that I know where we’re going, but I’m committed to you as a human being, and I’m going to be there for you.

FATHER DAVE KELLY (Director, Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation): Accompaniment is walking alongside. It’s very much a biblical kind of thing of just accompanying someone on the journey. Being there on that journey. Not necessarily that I know where we’re going, but I’m committed to you as a human being, and I’m going to be there for you.

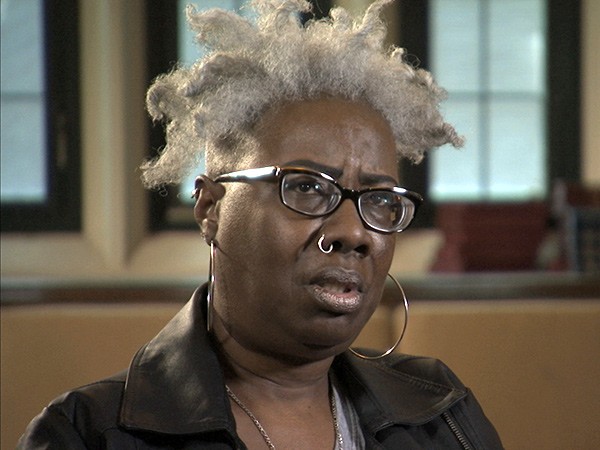

REV. SUSAN JOHNSON (Chicago Survivors): We have communities and families that are super-saturated with the experience of violence over multiple generations.

VALENTE: Reverend Susan Johnson is an American Baptist minister. She runs a program called Chicago Survivors. Police call in Chicago Survivors as soon as a homicide occurs to help families in the immediate aftermath of a violent death.

REV. JOHNSON: We’ll go with them to the medical examiner’s office to identify the body. We’ll talk with the police with them just to give them that security that they’re not just at-large in the midst of this crisis.

VALENTE: Among the hardest cases to handle are incidents of random violence. Louise Buckner’s husband, John, was gunned down by a teenager who rode by their home on a bicycle while they were unloading groceries from a car.

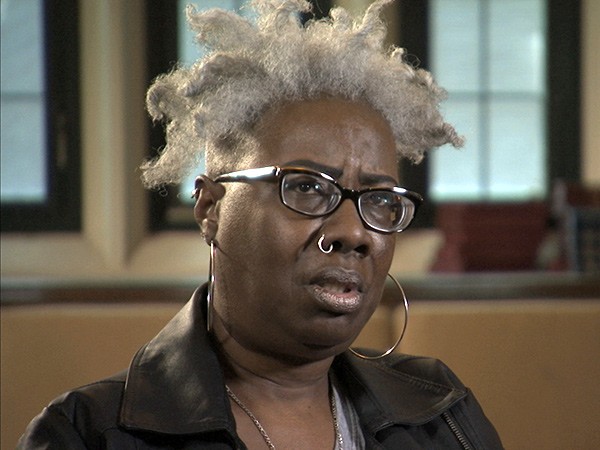

LOUISE BUCKNER: It has changed me forever. My family will never be the same again, you know. Someone coming to take a life from you for no reason.

LOUISE BUCKNER: It has changed me forever. My family will never be the same again, you know. Someone coming to take a life from you for no reason.

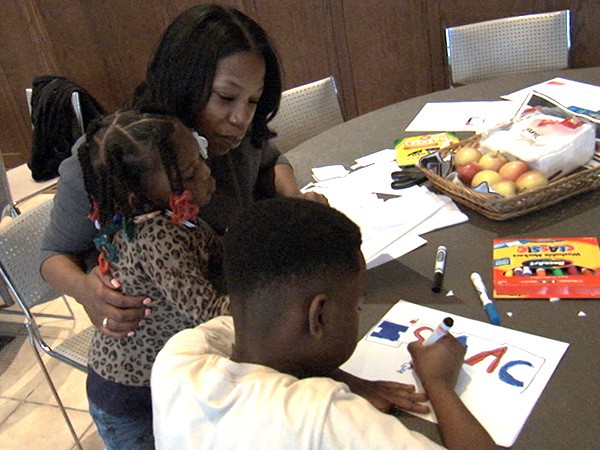

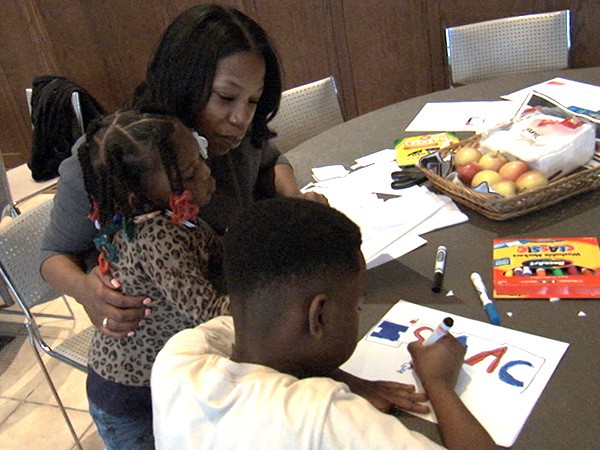

VALENTE: Ja-Chare Williams saw the father of her three children gunned down last year at their home by an acquaintance, in front of her four-year-old daughter.

JA-CHARE WILLIAMS: It’s just like she’s a newborn baby all over again. She want to be hugged and loved on now and wants to be reassured that my life not gonna be taken away.

REV. JOHNSON: I think we grossly underestimate the impact on children in urban neighborhoods where they grow up with an awareness of violence, with a personal experience of violence. When we look at children who are not performing well in school, whose attendance isn’t good at school, we should ask ourselves, where’s the trauma in this child’s life, and how can we intervene?

VALENTE: Williams did not want to remain with her children in the home where the shooting occurred. For months, she found herself moving from one relative’s or friend’s apartment to another. Chicago Survivors proved the one constant in her life.

WILLIAMS: They provided counseling. They also took me around to take care of a lot of business that I wasn’t able to do, that I was afraid to get on the bus and do.

WILLIAMS: They provided counseling. They also took me around to take care of a lot of business that I wasn’t able to do, that I was afraid to get on the bus and do.

VALENTE: No arrests have been made so far in either the Buckner or Williams shootings. Father Kelly, the juvenile detention center chaplain, says even if suspects were arrested, incarceration is only a partial answer at best to curbing the violence.

FATHER KELLY: There’s a lot of research that says it does more harm than good. And what it does as well, because it’s so costly, is that it takes from the community. So the resources we need in this community—good schools, really good schools, mental health, jobs—those are nonexistent because of the cost factor, if you will, of incarceration.

VALENTE: Kelly says there are other ways to hold kids accountable for their actions, especially those involved in nonviolent crimes. He’s a proponent of an alternative known as “restorative justice.”

FATHER KELLY: Basically, I look at crime or violence as a violation of relationships. Some people are harmed, some people do that harm. So the role of restorative justice is to repair, as best we can, those relationships.

JUDGE COLLEEN SHEEHAN (Cook County Juvenile Court): I think it seeks answers as to why someone has done something. If you know why someone has done something, if you know why you’ve done something, you can go about changing behavior.”

JUDGE COLLEEN SHEEHAN (Cook County Juvenile Court): I think it seeks answers as to why someone has done something. If you know why someone has done something, if you know why you’ve done something, you can go about changing behavior.”

VALENTE: Kelly has gained a powerful ally in Cook County Juvenile Judge Colleen Sheehan. Sheehan says she realized in her first year in juvenile court that she needed to look for innovative ways to rescue kids from the cycle of violence.

JUDGE SHEEHAN: When I came to juvenile court after the first year, there was a tally of five children who were on my probation that had been murdered. By the second year, the number had risen to twelve. It had a big effect on me. It was like, hey, what’s going on here, and what are we doing about this?

VALENTE: Sheehan began looking at alternatives to traditional courts. She has proposed establishing a series of restorative justice community courts. Instead of a traditional courtroom, young defendants would go to a place like the Precious Blood Center for Reconciliation, and participate in a peace circle, similar to the ones held for mothers struggling with the death of a child. Both Kelly and Sheehan say a key component of restorative justice is that community members must be involved.

FATHER KELLY: If it’s going to be a sustained effort, it cannot be a policing strategy. It’s got to be a community strategy. It’s got to be the community kind of coming together and really dealing with the issues.

VALENTE: Sheehan already has ordered juvenile defendants to attend restorative justice peace circles. She’s even convened peace circles for police and teens. She admits she was surprised by the reaction she got from a defendant in her courtroom when she proposed the idea.

VALENTE: Sheehan already has ordered juvenile defendants to attend restorative justice peace circles. She’s even convened peace circles for police and teens. She admits she was surprised by the reaction she got from a defendant in her courtroom when she proposed the idea.

JUDGE SHEEHAN: I said would you be interested in sitting with the police in a safe space, not invested in being a victim or blaming, but actually invested in solution? What if I gave you credit for those community service hours, I said. Would you be interested? He just looked at me, he stood back and just looked at me and said, “I’ll do it for free.”

VALENTE: Police Lieutenant Laurel Bresnahan, shown here in a video made after the event, was at first skeptical.

LIEUTENANT LAUREL BRESNAHAN: She sort of flipped the tables, and she asked us as police officers how we felt when we interact with community, some of the things we dealt with, and I thought, wow, maybe someone is actually going to listen to what we have to say as well when it was a very empowering thing.

Young Man (Speaking in Community Justice Youth Institute Video): The one thing I’m gonna take away from today is to be more understanding, to see everyone as not just a uniform.

JUDGE SHEEHAN: I mean, there were police officers who said “I’m sorry,” there were children who said they were sorry, and it was—there were real connections going on.

VALENTE: In another of her initiatives, Sheehan sponsored a photography contest for police and teenagers called “Bridging the Divide,” another idea that sprang from her courtroom experience.

Nearly all who work with those whose lives have been affected by violence say it is a deeply spiritual experience.

REV. JOHNSON: I talk about the compassion that we see in the community of survivors, the fellow-feeling, the empathy, and the forgiveness. It comes out of a spiritual searching that people who haven’t had a firsthand experience don’t have to go through.

REV. JOHNSON: I talk about the compassion that we see in the community of survivors, the fellow-feeling, the empathy, and the forgiveness. It comes out of a spiritual searching that people who haven’t had a firsthand experience don’t have to go through.

JUDGE SHEEHAN: Sometimes it feels as if I keep trying to do things differently and trying to push innovative ideas because I see something in front of me and I feel compelled to act. And sometimes it feels as if there is a certain divinity that happens.

FATHER KELLY: My work is between Good Friday, which is death, and Easter. Too often, as Christians, we want to move from Good Friday to Easter, and we forget about Holy Saturday, which is the real work of the church, because most of us are living in the shadow of the crucifixion, wanting the resurrection, wanting that new life, that freedom, that liberation. And we’re not there yet. And we work in this Holy Saturday moment.

VALENTE: It is that hope of something better that continues to inspire survivors and those working to stop the violence.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Judy Valente in Chicago.

JUDY VALENTE, correspondent: A Saturday morning at the Catholic Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation on Chicago’s South Side. Mothers from across the city gather for a healing circle, led by Sister Donna Liette.

JUDY VALENTE, correspondent: A Saturday morning at the Catholic Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation on Chicago’s South Side. Mothers from across the city gather for a healing circle, led by Sister Donna Liette. VALENTE: And then each mother tells her story:

VALENTE: And then each mother tells her story: FATHER DAVE KELLY (Director, Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation): Accompaniment is walking alongside. It’s very much a biblical kind of thing of just accompanying someone on the journey. Being there on that journey. Not necessarily that I know where we’re going, but I’m committed to you as a human being, and I’m going to be there for you.

FATHER DAVE KELLY (Director, Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation): Accompaniment is walking alongside. It’s very much a biblical kind of thing of just accompanying someone on the journey. Being there on that journey. Not necessarily that I know where we’re going, but I’m committed to you as a human being, and I’m going to be there for you. LOUISE BUCKNER: It has changed me forever. My family will never be the same again, you know. Someone coming to take a life from you for no reason.

LOUISE BUCKNER: It has changed me forever. My family will never be the same again, you know. Someone coming to take a life from you for no reason. WILLIAMS: They provided counseling. They also took me around to take care of a lot of business that I wasn’t able to do, that I was afraid to get on the bus and do.

WILLIAMS: They provided counseling. They also took me around to take care of a lot of business that I wasn’t able to do, that I was afraid to get on the bus and do. JUDGE COLLEEN SHEEHAN (Cook County Juvenile Court): I think it seeks answers as to why someone has done something. If you know why someone has done something, if you know why you’ve done something, you can go about changing behavior.”

JUDGE COLLEEN SHEEHAN (Cook County Juvenile Court): I think it seeks answers as to why someone has done something. If you know why someone has done something, if you know why you’ve done something, you can go about changing behavior.” VALENTE: Sheehan already has ordered juvenile defendants to attend restorative justice peace circles. She’s even convened peace circles for police and teens. She admits she was surprised by the reaction she got from a defendant in her courtroom when she proposed the idea.

VALENTE: Sheehan already has ordered juvenile defendants to attend restorative justice peace circles. She’s even convened peace circles for police and teens. She admits she was surprised by the reaction she got from a defendant in her courtroom when she proposed the idea. REV. JOHNSON: I talk about the compassion that we see in the community of survivors, the fellow-feeling, the empathy, and the forgiveness. It comes out of a spiritual searching that people who haven’t had a firsthand experience don’t have to go through.

REV. JOHNSON: I talk about the compassion that we see in the community of survivors, the fellow-feeling, the empathy, and the forgiveness. It comes out of a spiritual searching that people who haven’t had a firsthand experience don’t have to go through.