DAVID TERESHCHUK, correspondent: Pamela Prescott has been an educator for 38 years, a teacher who rose to be principal at a Christian school. Then things went badly wrong between her and her employers. A school board-member phoned her at home.

DAVID TERESHCHUK, correspondent: Pamela Prescott has been an educator for 38 years, a teacher who rose to be principal at a Christian school. Then things went badly wrong between her and her employers. A school board-member phoned her at home.

PAMELA PRESCOTT: He said we don’t need you to come back to campus at all. We are dismissing you. It was a very arduous and a very painful thing to go through.

TERESHCHUK: Cheri Spivey lost her son, Nick, when he was twenty years old and addicted to drugs. He died after she sent him to a Christian rehabilitation center.

CHERI SPIVEY: It was the worst, and still is. It’s just—a lot of times it’s just hard to believe that that happened, that Nick’s not here anymore.

CHERI SPIVEY: It was the worst, and still is. It’s just—a lot of times it’s just hard to believe that that happened, that Nick’s not here anymore.

TERESHCHUK: What the Prescott and Spivey cases have in common is that when each woman wanted to take legal action over their losses their way was blocked by the old, but rarely discussed, practice of Christian arbitration.

SPIVEY: I didn’t know what that was. I didn’t have a clue. I had heard of mediation before, but Christian arbitration I had not heard of.

BRYCE THOMAS (Christian Arbitrator): It’s a poor witness to our God and to our faith if our first resort is to take things to court.

TERESHCHUK: Bryce Thomas, besides being a licensed attorney in North Carolina, is a nationally prominent Christian arbitrator who works with the Institute of Christian Conciliation. The institute’s rules govern most of the Christian arbitrations that take place in America.

THOMAS: You might work with both sides and you bring them together in a safe environment where they can have the most open, candid conversation, and face all the stuff between them. One might owe the other money, and they say we need somebody to decide what is fair. We can’t arrive at what is fair. We’re going to tell you all the facts, and then you make a ruling, much like a judge would.

THOMAS: You might work with both sides and you bring them together in a safe environment where they can have the most open, candid conversation, and face all the stuff between them. One might owe the other money, and they say we need somebody to decide what is fair. We can’t arrive at what is fair. We’re going to tell you all the facts, and then you make a ruling, much like a judge would.

TERESHCHUK: Arbitration has long been accepted as an alternative for settling disputes without resorting to a court of law. Recently, though, there’s been controversy over companies and organizations using it to avoid their legal obligations, and demands have grown for new laws to ban abuses. But however arbitration may have been used or misused, it has rarely been seen as having anything to do with religion. That too has been changing.

What’s less well-known is the rise in arbitration that’s religious in nature, specifically Christian arbitration. And it’s rising even among organizations that engage in purely secular business, like this company selling hardwoods in the Pacific Northwest. Scroll down all the terms and conditions and you’ll see you’re agreeing to  submit any dispute you may ever have with the company to Christian arbitration held in Seattle under Christian conciliation rules. And it’s the same with a very different business—this one renting out vacation cabins in North Carolina. Rent one of these, and you’re promising to undergo “binding arbitration in accordance with the rules of procedure for Christian conciliation.”

submit any dispute you may ever have with the company to Christian arbitration held in Seattle under Christian conciliation rules. And it’s the same with a very different business—this one renting out vacation cabins in North Carolina. Rent one of these, and you’re promising to undergo “binding arbitration in accordance with the rules of procedure for Christian conciliation.”

Christian arbitration is said to have biblical precedent. The Apostle Paul insisted in his First Letter to the Corinthians that the early church members should avoid turning to civil legal authorities for resolving internal disputes and instead come to a settlement among themselves. Thomas and other arbitrators like him use precepts laid down in the Old and New Testaments to guide their rulings. One of the nation’s few experts on this specialty is in California. He’s a Jewish rabbi, Michael Helfand, who’s a law professor at Pepperdine University.

PROFESSOR MICHAEL HELFAND (Pepperdine University Law School): At its best, religious arbitration is an opportunity for two parties who have shared religious values to resolve those disputes in accordance with their religious values.

PROFESSOR MICHAEL HELFAND (Pepperdine University Law School): At its best, religious arbitration is an opportunity for two parties who have shared religious values to resolve those disputes in accordance with their religious values.

TERESHCHUK: Professor Helfand emphasizes the constitutional separation of church and state. He says this prevents courts from taking sides in a difference of religious opinion or practice between, for instance, a faith institution and its employees.

HELFAND: And if you didn’t have religious arbitration you’d be saying to all these employees, “There’s nowhere else for you to seek justice.”

TERESHCHUK: The case of Pam Prescott seemed to raise such an issue of religious differences when she was fired from the school where she was principal, and which we have agreed not to name, at Prescott’s request.

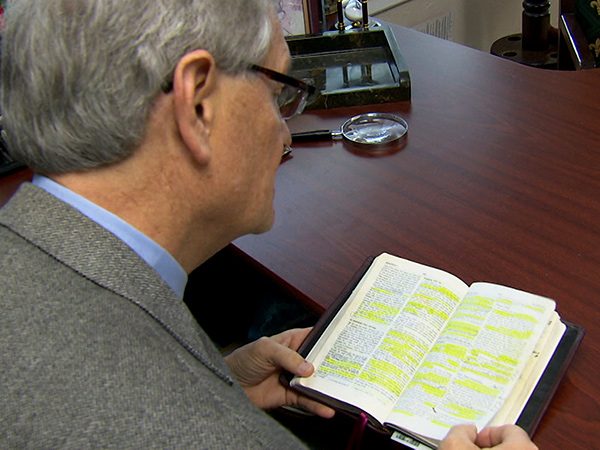

PRESCOTT: I’m a biblically based believer, so my religion is the scripture.

PRESCOTT: I’m a biblically based believer, so my religion is the scripture.

TERESHCHUK: Prescott’s contract of employment required her to waive her normal right to sue for wrongful dismissal if aggrieved.

PRESCOTT: The contract also made this Christian arbitration—conciliation, mediation, and arbitration—mandatory. I did not have the opportunity to take it to court.

TERESHCHUK: Though she had signed the waiver, she was upset to find her employers dragging their feet for years over the Bible-based alternative that was stipulated. But eventually both sides did get to a formal arbitration, presided over by Bryce Thomas.

THOMAS: I had something like 20, 30 witnesses that I listened to, and probably thousands of pages of documents.

PRESCOTT: Seven days—it went on that long, with calling witnesses. And before this we had to have depositions, just like you would do it in a civil court. And a ruling was rendered by the arbitrator, who ruled in my favor.

TERESHCHUK: Arbitrator Thomas ordered the school to pay Prescott about $160,000 to cover lost income and damage to her reputation.

TERESHCHUK: Arbitrator Thomas ordered the school to pay Prescott about $160,000 to cover lost income and damage to her reputation.

THOMAS: We’re not there to please either party. We’re trying to render a decision that’s God-pleasing, first of all, and secondly blesses both parties. But we’ve got to deal with truth.

TERESHCHUK: The school certainly wasn’t pleased with the arbitrator’s finding, and tried to appeal it, surprisingly enough, in the civil courts. The appeal failed, but Prescott’s legal costs wiped out almost every dollar she had been awarded. The school declined to discuss the case with us, on the grounds that it concerned actions by a past administration.

The Spivey family’s distressing arbitration experience came when Cheri Spivey tried to sue the Christian drug-rehab, Teen Challenge, for the wrongful death of her son.

SPIVEY: I wanted someone to answer, you know, me, you know. You all told me Nick was doing really well. What happened, what went wrong? He’s only been there 30 days. Just so many questions, you know, and they were refusing to give me any information.

SPIVEY: I wanted someone to answer, you know, me, you know. You all told me Nick was doing really well. What happened, what went wrong? He’s only been there 30 days. Just so many questions, you know, and they were refusing to give me any information.

TERESHCHUK: Spivey discovered that her son had signed a waiver while he was being admitted to the rehab, most likely still high on drugs. It said that he (or his estate, should he die) would give up all rights to sue Teen Challenge in court and would instead undergo Christian arbitration.

SPIVEY: My attorney would not be able to speak at all. She could attend, but she would have to sit in the back and not talk. It was led by all Christians, and to me it felt like we would go in there and pray, do Bible study, kiss and make up, and I wasn’t willing to do that.

TERESHCHUK: Eventually the matter was settled, at least in financial terms, with Teen Challenge paying out an undisclosed sum of money. Teen Challenge declined comment on the case to us. Spivey remains unsatisfied about the facts surrounding her oldest child’s death and frustrated in her efforts to find them out.

SPIVEY: They don’t give you the opportunity to get justice. Some things you can’t just sweep under the rug and say, you know, I’m sorry that happened. Let’s move forward from here. For some things “I’m sorry” is just not enough. And ultimately that’s what Christian arbitration is—is, you know, everybody just finds a way to get along.

TERESHCHUK: Experts in the field, however, remain convinced that religious arbitration works well side-by-side with secular law.

HELFAND: The match between the systems is pretty good, and here’s why. On the one hand, American law makes sure that the process is fair, and on this side of the equation you have Jewish law, Islamic law, Christian forms of law making sure that the rights and responsibilities match the religious expectations of the parties.

HELFAND: The match between the systems is pretty good, and here’s why. On the one hand, American law makes sure that the process is fair, and on this side of the equation you have Jewish law, Islamic law, Christian forms of law making sure that the rights and responsibilities match the religious expectations of the parties.

THOMAS: The fact that we rely primarily on Holy Scripture, I don’t think that needs improving.

TERESHCHUK: All the same, aggrieved parties in the religious arbitration process can often be left feeling that the system too easily works against them. At the least, it leaves them wary, certainly about the religious label.

PRESCOTT: I haven’t lost faith in Christianity or Christians. It’s just that I am more careful with the idea of—the name doesn’t mean anything.

TERESHCHUK: For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is David Tereshchuk reporting.

DAVID TERESHCHUK, correspondent: Pamela Prescott has been an educator for 38 years, a teacher who rose to be principal at a Christian school. Then things went badly wrong between her and her employers. A school board-member phoned her at home.

DAVID TERESHCHUK, correspondent: Pamela Prescott has been an educator for 38 years, a teacher who rose to be principal at a Christian school. Then things went badly wrong between her and her employers. A school board-member phoned her at home. CHERI SPIVEY: It was the worst, and still is. It’s just—a lot of times it’s just hard to believe that that happened, that Nick’s not here anymore.

CHERI SPIVEY: It was the worst, and still is. It’s just—a lot of times it’s just hard to believe that that happened, that Nick’s not here anymore. THOMAS: You might work with both sides and you bring them together in a safe environment where they can have the most open, candid conversation, and face all the stuff between them. One might owe the other money, and they say we need somebody to decide what is fair. We can’t arrive at what is fair. We’re going to tell you all the facts, and then you make a ruling, much like a judge would.

THOMAS: You might work with both sides and you bring them together in a safe environment where they can have the most open, candid conversation, and face all the stuff between them. One might owe the other money, and they say we need somebody to decide what is fair. We can’t arrive at what is fair. We’re going to tell you all the facts, and then you make a ruling, much like a judge would. submit any dispute you may ever have with the company to Christian arbitration held in Seattle under Christian conciliation rules. And it’s the same with a very different business—this one renting out vacation cabins in North Carolina. Rent one of these, and you’re promising to undergo “binding arbitration in accordance with the rules of procedure for Christian conciliation.”

submit any dispute you may ever have with the company to Christian arbitration held in Seattle under Christian conciliation rules. And it’s the same with a very different business—this one renting out vacation cabins in North Carolina. Rent one of these, and you’re promising to undergo “binding arbitration in accordance with the rules of procedure for Christian conciliation.” PROFESSOR MICHAEL HELFAND (Pepperdine University Law School): At its best, religious arbitration is an opportunity for two parties who have shared religious values to resolve those disputes in accordance with their religious values.

PROFESSOR MICHAEL HELFAND (Pepperdine University Law School): At its best, religious arbitration is an opportunity for two parties who have shared religious values to resolve those disputes in accordance with their religious values. PRESCOTT: I’m a biblically based believer, so my religion is the scripture.

PRESCOTT: I’m a biblically based believer, so my religion is the scripture. TERESHCHUK: Arbitrator Thomas ordered the school to pay Prescott about $160,000 to cover lost income and damage to her reputation.

TERESHCHUK: Arbitrator Thomas ordered the school to pay Prescott about $160,000 to cover lost income and damage to her reputation. SPIVEY: I wanted someone to answer, you know, me, you know. You all told me Nick was doing really well. What happened, what went wrong? He’s only been there 30 days. Just so many questions, you know, and they were refusing to give me any information.

SPIVEY: I wanted someone to answer, you know, me, you know. You all told me Nick was doing really well. What happened, what went wrong? He’s only been there 30 days. Just so many questions, you know, and they were refusing to give me any information. HELFAND: The match between the systems is pretty good, and here’s why. On the one hand, American law makes sure that the process is fair, and on this side of the equation you have Jewish law, Islamic law, Christian forms of law making sure that the rights and responsibilities match the religious expectations of the parties.

HELFAND: The match between the systems is pretty good, and here’s why. On the one hand, American law makes sure that the process is fair, and on this side of the equation you have Jewish law, Islamic law, Christian forms of law making sure that the rights and responsibilities match the religious expectations of the parties.