LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: This is Utah state legislator Mike Noel on his ATV [all-terrain vehicle], his four-wheeler, checking cattle on his ranch in southern Utah. He also has horses to get around on.

LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: This is Utah state legislator Mike Noel on his ATV [all-terrain vehicle], his four-wheeler, checking cattle on his ranch in southern Utah. He also has horses to get around on.

MIKE NOEL: Six-hundred-fifty pound calf last year was $1500 a head, so yeah, it’s the best in history.

SEVERSON: Noel is a leader in the so-called “Sagebrush Rebellion,” a decades-long battle to take back federal public lands and put them in the hands of local governments. The rebellion seemed to have faded until the recent armed confrontations in Oregon and Nevada. It is an epic struggle over who controls the vast, scenic lands in the American West, and it is a battle with religious overtones.

WILL BAGLEY: The Sagebrush Rebellion traces itself directly back to the fiery sermons of Brigham Young in the Adobe Tabernacle in Utah in the 1850s.

SEVERSON: Will Bagley is a historian who has written more than 20 books about the West and the church, whose pioneers settled so many communities throughout the Rocky Mountain States.

BAGLEY: I’ve found seven distinct similarities between what sagebrush rebels believe and what frontier Mormons believe. Both parties believe state’s rights are second only to Scripture. The government persecutes them because they’re righteous, and they’re the only true patriots. They love the Constitution, but they hate the government.

BAGLEY: I’ve found seven distinct similarities between what sagebrush rebels believe and what frontier Mormons believe. Both parties believe state’s rights are second only to Scripture. The government persecutes them because they’re righteous, and they’re the only true patriots. They love the Constitution, but they hate the government.

SEVERSON: Shawna Cox fits that description. She is from Kanab, but joined the protestors in Oregon

SHAWNA COX: Public land is for the people who live here, okay? It’s not for people from New York who come out into Utah, and that’s their public land. They don’t live here.

NOEL: It’s hard to fight the federal government, Lucky, it really is. There’s a lot of people that support us. Arizona supports us. Nevada supports us. Wyoming supports us. Idaho supports us.

SEVERSON: Noel’s ranch is just outside of Kanab, Utah, a small city surrounded by rugged beauty that may seem familiar from film and television.

SEVERSON: Noel’s ranch is just outside of Kanab, Utah, a small city surrounded by rugged beauty that may seem familiar from film and television.

FRED ALLEN: My father nicknamed us children after movie stars, because we all worked in the movies.

SEVERSON: This is Fred Allen, the Kanab barber named after the famous Hollywood comedian. More than 100 films have been shot here—classic westerns that embodied the American ideal of rugged, heroic cowboys living on the lonely western frontier. Now it’s much more difficult to be lonely. Tourists are everywhere.

To control the crowds, Bureau of Land Management rangers now must conduct a lottery, because only a few at a time can be allowed into some pristine parts like The Wave, a remote and exquisite place

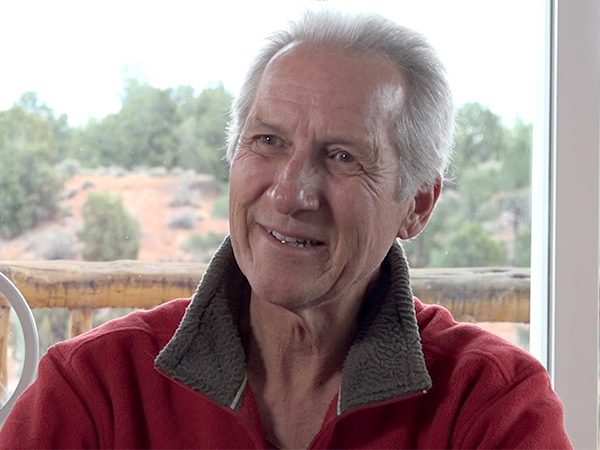

It was the beauty that brought retired psychology professor Sky Chaney and his wife to this area 10 years ago.

SKY CHANEY: I’m concerned that if the state gains ownership and starts selling off there will be beautiful places like where we’re standing right now that are going to be developed.

SKY CHANEY: I’m concerned that if the state gains ownership and starts selling off there will be beautiful places like where we’re standing right now that are going to be developed.

SEVERSON: For the Chaneys, moving to Kanab was an adjustment.

CHANEY: I’d never lived in a town that was more than 50 percent Mormon or any one religion.

SEVERSON: Chaney was shocked to learn that the county was using so much taxpayer money fighting the federal government. So he founded the Taxpayers Association of Kane County.

Is it just outsiders like yourself that are the troublemakers here as far as they’re concerned?

CHANEY: I think so. I think that the local Mormon community that’s been here longer has a fear that outsiders are going to take over their town.

SEVERSON: Kanab is very conservative and very Mormon. Another protestor in the recent Oregon refuge standoff was originally from here and claimed Mormon teachings influenced his actions. LaVoy Finnicum, ended up being shot and killed when the standoff ended.

SEVERSON: Kanab is very conservative and very Mormon. Another protestor in the recent Oregon refuge standoff was originally from here and claimed Mormon teachings influenced his actions. LaVoy Finnicum, ended up being shot and killed when the standoff ended.

The Mormon Church publically condemned the takeover and the militia members’ justification that it was because of Mormon Scripture.

MIKE NOEL: That’s a very, very, very important point for me as an active member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Once the brethren speak and say that’s not—you shouldn’t be up there, you should have come home.

SEVERSON: Many of the protesters in Oregon and Nevada carry copies of the US Constitution in their shirt pocket. There are apparently about 15 million of these in print. They’re called pocket Constitutions, and they’ve become like a Bible for the Sagebrush Rebellion.

NOEL: We believe strongly that the Constitution was divinely inspired, and even the founders of it were inspired to write the Constitution.

SEVERSON: Shawna Cox was one of the protestors in Oregon arrested. She was with LaVoy Finnicum when he was shot. She is not allowed to speak about the case.

SEVERSON: Shawna Cox was one of the protestors in Oregon arrested. She was with LaVoy Finnicum when he was shot. She is not allowed to speak about the case.

COX: If you want to call a militia person a bad person because they want to protect themselves or their neighbors, then I know that that’s wrong, because the Constitution affords us that right.

SEVERSON: Pat Shea is a former director of the Bureau of Land Management [BLM], now a research professor of biology at the University of Utah. He says the first round of the Sagebrush Rebellion began in 1976, when Congress approved a land management act.

PROFESSOR PATRICK SHEA (Research Professor, Biology, University of Utah): The second round happened really in the mid-1990s when President Clinton declared the Grand  Staircase Escalante, and there was an outrage again that the federal government was usurping local authority and state government authority.

Staircase Escalante, and there was an outrage again that the federal government was usurping local authority and state government authority.

SEVERSON: The Grand Staircase Escalante is called a national monument. It is the country’s largest, covering 3000 square miles. There are now seven such national monuments in Utah, but enough is enough as far as Garfield County Commissioner Leland Pollock is concerned. A good portion of the Grand Staircase is in Garfield County.

LELAND POLLOCK: To come into these areas and do it by way of a president stamping down a stamp and saying this is a monument, and tying up land and doing it that way—that’s not the American way to change to culture.

SEVERSON: In fact, presidents dating back to Teddy Roosevelt have set aside many national monuments. Roosevelt championed preserving America’s West against commercial exploitation. But the commissioner says the Staircase locks up too much of his county.

POLLOCK: If you take grazing out of Garfield Country you have changed a culture. Multiple use is a culture.

POLLOCK: If you take grazing out of Garfield Country you have changed a culture. Multiple use is a culture.

SHEA: I think multiple use—that could be sustained. If you use up all the water, you can’t sustain it. If you use up all grazing area, you can’t sustain it.

SEVERSON: But even though tourism is often the state’s number one industry, much bigger than ranching and farming, it’s the idea that the federal government controls so much land that causes such righteous indignation and violates their religious beliefs.

NOEL: There’s too much of an ability for individuals that are unelected to be able to take control of the lands and then take control of your life, really.

COX: I know that this is a war between good and evil.

SHEA: I think the thing that we need to do is tone down the rhetoric, which is becoming very dangerous.

SEVERSON: While the consensus around here is that the government has been heavy handed, the tourism business is better than ever, and even some critics have grown weary of the fight, like Fred Allen, the barber, who takes the longer view.

SEVERSON: While the consensus around here is that the government has been heavy handed, the tourism business is better than ever, and even some critics have grown weary of the fight, like Fred Allen, the barber, who takes the longer view.

ALLEN: When the millennium happens and the Savior comes again, all this coal that’s on public land, it’s still here. All this public land is still here. It’s not going anywhere. It will just be administered by the Savior, rather than by a government entity.

SEVERSON: The next big hurdle could come later this year when—and if—President Obama designates a new national monument, also projected for southern Utah not far from the the Grand Staircase.

LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: This is Utah state legislator Mike Noel on his ATV [all-terrain vehicle], his four-wheeler, checking cattle on his ranch in southern Utah. He also has horses to get around on.

LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: This is Utah state legislator Mike Noel on his ATV [all-terrain vehicle], his four-wheeler, checking cattle on his ranch in southern Utah. He also has horses to get around on. BAGLEY: I’ve found seven distinct similarities between what sagebrush rebels believe and what frontier Mormons believe. Both parties believe state’s rights are second only to Scripture. The government persecutes them because they’re righteous, and they’re the only true patriots. They love the Constitution, but they hate the government.

BAGLEY: I’ve found seven distinct similarities between what sagebrush rebels believe and what frontier Mormons believe. Both parties believe state’s rights are second only to Scripture. The government persecutes them because they’re righteous, and they’re the only true patriots. They love the Constitution, but they hate the government. SEVERSON: Noel’s ranch is just outside of Kanab, Utah, a small city surrounded by rugged beauty that may seem familiar from film and television.

SEVERSON: Noel’s ranch is just outside of Kanab, Utah, a small city surrounded by rugged beauty that may seem familiar from film and television. SKY CHANEY: I’m concerned that if the state gains ownership and starts selling off there will be beautiful places like where we’re standing right now that are going to be developed.

SKY CHANEY: I’m concerned that if the state gains ownership and starts selling off there will be beautiful places like where we’re standing right now that are going to be developed. SEVERSON: Kanab is very conservative and very Mormon. Another protestor in the recent Oregon refuge standoff was originally from here and claimed Mormon teachings influenced his actions. LaVoy Finnicum, ended up being shot and killed when the standoff ended.

SEVERSON: Kanab is very conservative and very Mormon. Another protestor in the recent Oregon refuge standoff was originally from here and claimed Mormon teachings influenced his actions. LaVoy Finnicum, ended up being shot and killed when the standoff ended. SEVERSON: Shawna Cox was one of the protestors in Oregon arrested. She was with LaVoy Finnicum when he was shot. She is not allowed to speak about the case.

SEVERSON: Shawna Cox was one of the protestors in Oregon arrested. She was with LaVoy Finnicum when he was shot. She is not allowed to speak about the case. Staircase Escalante, and there was an outrage again that the federal government was usurping local authority and state government authority.

Staircase Escalante, and there was an outrage again that the federal government was usurping local authority and state government authority. POLLOCK: If you take grazing out of Garfield Country you have changed a culture. Multiple use is a culture.

POLLOCK: If you take grazing out of Garfield Country you have changed a culture. Multiple use is a culture. SEVERSON: While the consensus around here is that the government has been heavy handed, the tourism business is better than ever, and even some critics have grown weary of the fight, like Fred Allen, the barber, who takes the longer view.

SEVERSON: While the consensus around here is that the government has been heavy handed, the tourism business is better than ever, and even some critics have grown weary of the fight, like Fred Allen, the barber, who takes the longer view.