LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: Robert Gill suffers from Kennedy’s disease and is receiving palliative care at a VA hospital in Palo Alto, California.

ROBERT GILL: Kennedy’s is like ALS, but ALS is fast. You die quick. My case is very slow.

DR. VJ PERIYAKOIL (Director of Palliative Care, Stanford Hospital and VA Hospital): So what does an up day look like compared to a down day?

GILL: Well, an up day is I’m feeling good, I’m not in pain. I’m just happy to be alive.

GILL: Well, an up day is I’m feeling good, I’m not in pain. I’m just happy to be alive.

SEVERSON: Gill is a navy veteran and a retired operations manager. He has decided he doesn’t want to spend the last days of his life tethered to machines and receiving all the treatments modern medical science has to offer.

GILL: Some people want to pity themselves. Others want to just say move on, enjoy life.

PERIYAKOIL: I think the biggest challenge is people don’t want to make plans and have discussions because the topic is so threatening to them. So what happens is because they don’t plan for it, they are subjected to treatments that are A, not helpful and B, not what they want.

SEVERSON: Dr. VJ Periyakoil is a nationally recognized Stanford University palliative and hospice care specialist. She says that far too many of the 2.6 million Americans projected to die this year will die in a hospital, even though a majority would rather die at home.

PERIYAKOIL: Dying is not being in the ICU, 20 tubes coming out of you, beeping everywhere, family is outside, doctors surrounding with their computers. That’s not what dying should be. Dying is a social, family, personal event. We really need to free dying from the hospital and take it back into the community where it belongs.

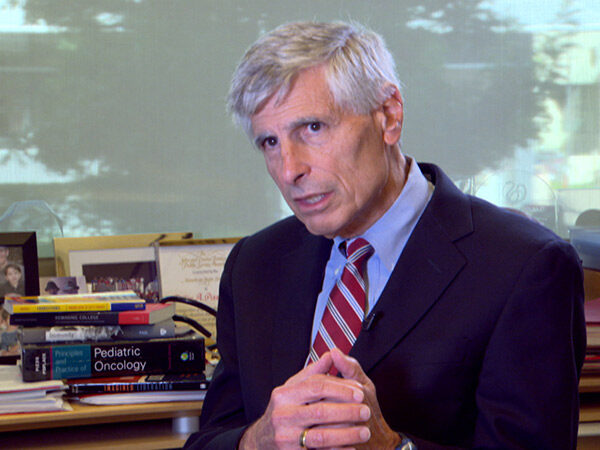

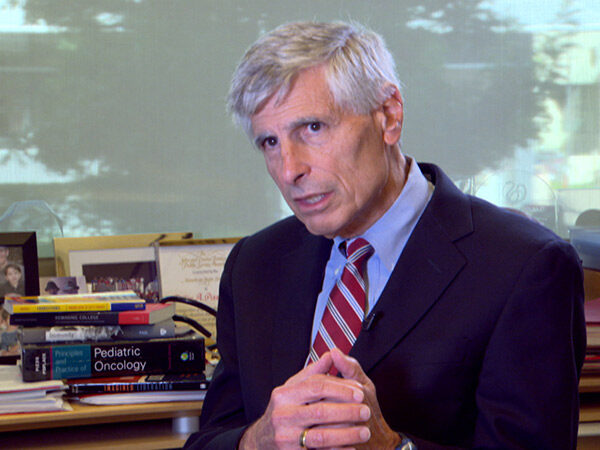

SEVERSON: It turns out the vast majority of American doctors don’t want to end their lives in a hospital either. Dr. Philip Pizzo is dean emeritus at the Stanford School of Medicine

DR. PHILIP PIZZO (Dean Emeritus, Stanford University School of Medicine): Anywhere from 80 to 95 percent of them say they want to die outside the hospital. They want to die at home, they want to have the family around them, they don’t want to be on life support systems, and they want to have coverage for their pain.

DR. PHILIP PIZZO (Dean Emeritus, Stanford University School of Medicine): Anywhere from 80 to 95 percent of them say they want to die outside the hospital. They want to die at home, they want to have the family around them, they don’t want to be on life support systems, and they want to have coverage for their pain.

SEVERSON: How about you?

PIZZO: Absolutely. I feel very much the same way, and I’ve thought very carefully about that, in terms of my care. And my wife and I have had very clear discussions about that, and we’ve had those discussions with our family as well.

SEVERSON: Dr. Pizzo co-chaired the Institute of Medicine committee that produced the 2014 “Dying in America” report, which strongly recommended end-of-life conversations, with palliative care for all patients with serious illnesses.

PERIYAKOIL: There is a tipping point in every illness, where the treatment becomes more burdensome than the disease itself. At which point you are keeping the body alive the person may not really recognize their family. They may not know who they are, they may never ever come back to the person they used to be, and at that point you have to pause and say, what am I doing here?

SEVERSON: Dr. Josh Wilfong, a Stanford palliative care and hospice fellow, said if he had an incurable disease he would only take treatments that would allow him to live comfortably.

DR. JOSH WILFONG: The hospital is a situation where people just lose their dignity. They wear gowns, they lie in bed all day, they are, in a way, dehumanized.

SEVERSON: It’s not only the loss of dignity. The cost of end-of-life care is overwhelming our medical system.

SEVERSON: The US spends about two-and-a-half times the average of most developed countries on health care, and end-of-life care in this country represents a disproportionate share of that expense. Almost 80 percent of costs in the final year of life are spent in the last month on intensive, aggressive treatments many patients don’t want.

Dr. Pizzo says the impact on health care costs is going to get much worse.

PIZZO: We are literally on the cusp. In the next 15 years, 20% of the population in the United States is going to be 65 years or older.

SEVERSON: And the way things have been going, most of those patients 65 and older will never have an end-of-life discussion. That’s a finding of a major study by Dr. VJ that

99 percent of doctors don’t like to do them.

PIZZO: It’s not easy to sit down with family or a child who may face end-of-life and have that kind of honest dialogue. You need to be taught how to do that.

PERIYAKOIL: Medical school trained me to go out there and save lives and to do everything I possibly can, so it’s much easier for me to say, let me do one more test.

PERIYAKOIL: Medical school trained me to go out there and save lives and to do everything I possibly can, so it’s much easier for me to say, let me do one more test.

PIZZO: Our healthcare system has so many perverse incentives that lead to doing more rather than less, and one of the things that it does is not permit physicians or other care providers to have enough time to really be able to sit down, and take the time to listen, and truly appreciate what the preferences of the family or the individual is about.

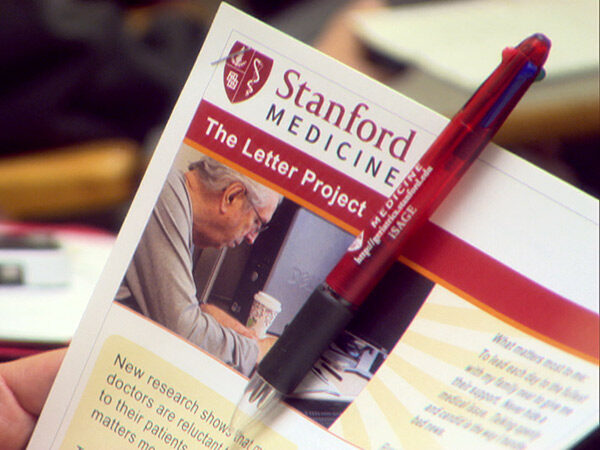

SEVERSON: Since doctors were not initiating these conversations, Dr. VJ created the Stanford Letter Project to allow patients and families to say what matters most to them at the end of their lives. Michael White’s brother, Jerry, recently died of cancer in a hospice. Now the retired firefighter wants to prepare for his own death in case he can’t speak for himself.

PERIYAKOIL: So, how do you make medical decisions for your family?

MICHAEL WHITE: My wife will decide. She knows how I am about quality of life.

PERIYAKOIL: If your heart were to stop do, you want us to attempt to resuscitate or restart your heart, or do you want us to allow you to go gently?

WHITE: I definitely do not want to be resuscitated.

PERIYAKOIL: Would you want to be on a breathing machine?

WHITE: No.

SEVERSON: Dr. VJ talks about end-of-life to just about anyone who will listen. Here she’s speaking to a large gathering of nurses, one of whom relates her experience with an 18-year-old patient who was grateful to have a candid conversation about his end of life.

STANFORD HOSPITAL NURSE: He was just so wise hearing that he was dying, hearing what it meant, and hearing what they could offer him. Everybody kind of left, including his mom, and he looked at me, and he had never looked me in the eyes, and he had never said thank you. He did both of those things, and he asked for a hug, and I hugged him, and we both cried.

PERIKYAKOIL: It’s truly a privilege to be there at the bedside of a dying patient and be there for the family. I’ve taken care of thousands of thousands of patients, and every single situation you learn something that you did not know before.

PERIKYAKOIL: It’s truly a privilege to be there at the bedside of a dying patient and be there for the family. I’ve taken care of thousands of thousands of patients, and every single situation you learn something that you did not know before.

SEVERSON: This is Chaplain Mark Goodwin:

REV MARK GOODWIN (Hospice and Palliative Care Chaplain, Stanford Health Care): Many times if it’s a spiritual question, they’re asking what’s going to happen to my soul, what’s going to happen to my essence when I die? I really try to help them draw on their own spiritual understandings so they can get to a place of peace with that.

GILL: I always wore my religion in my heart, only my heart. Nobody knew about my religion. But since coming here I just had a visit this morning by the chaplain, and I have about four visits a week, and I enjoy them.

SEVERSON: Dr. VJ is heartened, some might even say excited, that her letter-writing project is catching on in other parts of the country. That will be good news to Dr. Pizzo, whose report, “Dying in America,” was not very optimistic.

PIZZO: I think the headline, unfortunately, was that our approach to end-of-life care in the United States is still pretty broken and that we have a lot of work to do.

SEVERSON: One reason doctors have not been conducting end-of-life discussions is that they take time, and the doctors were not compensated. But as of 2016 Medicare will reimburse doctors who do take the time.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Lucky Severson in Palo Alto, California.

GILL: Well, an up day is I’m feeling good, I’m not in pain. I’m just happy to be alive.

GILL: Well, an up day is I’m feeling good, I’m not in pain. I’m just happy to be alive. DR. PHILIP PIZZO (Dean Emeritus, Stanford University School of Medicine): Anywhere from 80 to 95 percent of them say they want to die outside the hospital. They want to die at home, they want to have the family around them, they don’t want to be on life support systems, and they want to have coverage for their pain.

DR. PHILIP PIZZO (Dean Emeritus, Stanford University School of Medicine): Anywhere from 80 to 95 percent of them say they want to die outside the hospital. They want to die at home, they want to have the family around them, they don’t want to be on life support systems, and they want to have coverage for their pain. PERIYAKOIL: Medical school trained me to go out there and save lives and to do everything I possibly can, so it’s much easier for me to say, let me do one more test.

PERIYAKOIL: Medical school trained me to go out there and save lives and to do everything I possibly can, so it’s much easier for me to say, let me do one more test. PERIKYAKOIL: It’s truly a privilege to be there at the bedside of a dying patient and be there for the family. I’ve taken care of thousands of thousands of patients, and every single situation you learn something that you did not know before.

PERIKYAKOIL: It’s truly a privilege to be there at the bedside of a dying patient and be there for the family. I’ve taken care of thousands of thousands of patients, and every single situation you learn something that you did not know before.