JUDY VALENTE, correspondent: Newark, New Jersey—a city struggling to overcome a host of problems.

MARYLOU BONGIORNO: We’re talking about a 32 percent poverty rate, third highest in homicides in the nation, high unemployment, low academic performance from the high schools. So we’re looking at a city that is in great need and is suffering.

VALENTE: Marylou Bongiorno is a filmmaker who was working on a series of documentaries about her hometown when she discovered this place in Newark’s inner city: St. Benedict’s Preparatory School, led by a group of 13 Benedictine monks. With a student body that is 80 percent African American and Latino, the school has a near perfect graduation rate. Ninety-five percent of last year’s senior class went on to college. The secret to its success? St. Benedict’s operates more like a monastery than a school. The main subject taught here is community.

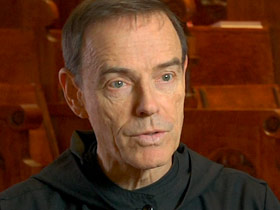

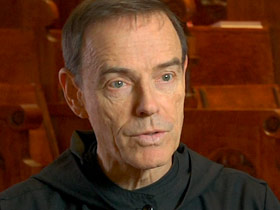

FATHER EDWIN LEAHY (Headmaster, St. Benedict's Preparatory School): You see signs all around the place, "Whatever Hurts My Brother Hurts Me," so to try to get kids to understand that, to live that. That’s the great sense of living in a monastery.

VALENTE: But St. Benedict’s is the school that almost wasn’t. It was established in 1848 to educate the sons of upwardly mobile Italian, Polish, Slovak, and Irish Catholics. But the riots of 1967 drove many white students from the school. After the Newark riots, and with enrollment dwindling, St. Benedict’s Prep closed for a year. A third of the monks left to live in another monastery, but a core remained behind, determined to revive this school.

LEAHY: We’re here as a sign of God’s presence, of faith. That’s kind of who we are as monks. We take a vow of stability of place, so even though the neighborhoods change around us on a regular basis, we stay.

VALENTE: It’s 9:15 a.m. Time for the entire school community to gather for the daily convocation, what the students refer to as “convo.” Color-coordinated sweat shirts identify the different classes. Student leaders report the day’s attendance, discuss upcoming activities. Everyone has a chance to say what’s on his mind. In the centuries-old tradition of monasteries, they sing a hymn, then pray “lauds,” or morning prayer.

St. Benedict’s has 13 buildings, an Olympic-size pool, two gyms, and a large theater for student-led productions. But few who attend can afford to pay the annual $12,500 tuition. The school must raise about six million dollars each year through alumni donations, and grants from corporations, foundations and area financial institutions.

Violence occurs daily in the neighborhoods where many of these students live. But here at St. Benedict’s, there are no security monitors or even locks on lockers. The emphasis is on personal responsibility.

LEAHY: So many times in schools they’re run so heavily from the top down. I don’t believe that’s helpful to kids, especially young men of color, because so much of their life they feel they have no control over.

VALENTE: Much of the school’s philosophy is based on the 1600-year-old guide to monastic living, “The Rule of St. Benedict.”

FATHER AUGUSTINE CURLEY: In terms of silence and in terms of relationship with God and community and forgiveness, you know, there is a lot in there that resonates with them, and I think it’s always amazing when they finally, when they look at the Rule and they say, "Oh, that’s why we do that here."

VALENTE: For instance, students who commit serious infractions, in most cases, are not suspended or expelled. Taking a page directly out of St. Benedict’s Rule, they are “excommunicated” for a time from the school community.

LEAHY: You’re trying to get them to reflect on their inappropriate behavior within the context of community, so you take them out of the community.

VALENTE: When Jaheer Jones, an otherwise stellar student, got into an uncharacteristic fight with another student, Father Edwin required him to assist at Mass on Saturday nights and participate in a Bible study. Like most of the 536 students here, Jones is not Catholic. He’s a Pentecostal Protestant. His mother welcomes the emphasis on Catholic monastic practices.

SELMA DANIELS (Jaheer Jones's Mother): The relationships that the monks have with the students, I do like the way they talk to them, I like the way they treat them, I like the way that they give them a sense of community and a sense, really, of hope.

VALENTE: Muqka Poole was impressed by a cousin who attended St. Benedict’s and then went on to college.

MUQKA POOLE: Going to college isn’t something I’m used to or my family is used to. So when I heard this I was surprised. So he told me, Muqka, you gotta go there. You gotta go to St. Benedict’s Prep. This is the school you got to go to.

VALENTE: Muqka has been accepted by St. John’s University in Minnesota. He is one of the 60 students who live on campus in a building next to the monastery.

POOLE: Well, my neighborhood is unsafe and dangerous. If I wasn’t living here, to tell you the truth, I’d probably be here at 11:30 at night anyway.

VALENTE: There is also a strong emphasis on counseling, which takes place daily, as if it were a core subject.

IVAN LAMOURT (School Counselor): None of us likes to look at ourselves when things are difficult.

VALENTE: Groups like “Unknown Sons,” whose members never knew or have little contact with their dads.

STUDENT: I’m here because I don’t know anything about my biological father.

STUDENT: I’m here because I don’t talk to my dad at all.

LAMOURT: "I’m here because I’m hurting so bad on the inside, but I can’t show you, because I’m a man. And if I’m a man of color, the only way I can express an emotion is violently."

LEAHY: What we’ve discovered is a lot of what manifests itself outwardly as poor academic performance has very little if anything to do with cognition. I mean, it has to do with emotional distress that a young man’s going through, so that they begin to turn that anger in on themselves and little by little destroy themselves.

VALENTE: But St. Benedict’s can’t always protect its students from outside influences. Tyrone Heggins was a student leader who went on to the University of Delaware. But just six weeks before his college graduation...

TYRONE HEGGINS: I participated in an armed robbery with three other students which led to my incarceration for three years.

VALENTE: He served his time, and a court has since expunged his criminal record. He now works for a corporation where he’s been placed on a management track.

Teachers College at New York’s Columbia University is considering writing a study guide that uses St. Benedict’s as a model for urban education. Father Edwin says he’s asked all the time if St. Benedict’s methods can be replicated elsewhere.

LEAHY: I think two things are essential. Whoever is the head of the school needs to live there. It needs to be open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. And in order to do that you’ve got to, it seems to me you have to have some kind of community present.

VALENTE: As with most American monasteries, few monks have joined Newark Abbey in recent years. There is some concern about what will happen to the school if the monastic community doesn’t grow. And raising six million dollars a year is always a battle. Father Edwin says he doesn’t spend too much time worrying.

LEAHY: All I can hear is the voice of the Lord to Moses, "Go forward. Don’t stop, and a way will open."

VALENTE: Father Edwin says, in the end, it’s all about teaching these young men that their lives have meaning.

LEAHY: "Who am I? What am I here for?" Now when you talk to a teenager about that, they look at you, they roll their eyes. So you teach so that they have something to refer to when these questions begin to well up in their heart about the meaning of life, the meaning of their life, their life in the face of death and what does it all mean.

VALENTE: And as long as there is even a single monk left, Father Edwin says that is the mission St. Benedict’s Prep will continue to carry out in the heart of this city.

For Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, I’m Judy Valente in Newark, New Jersey.

BOB ABERNETHY, host: St. Benedict’s Prep is the subject of a documentary film by Marylou and Jerome Bongiorno called “The Rule,” which appears on many PBS stations and is available online through a link on our website. The Bongiornos are now working on a fictionalized feature film about the school. It’s working title: “Monks in the Hood.”