FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: For decades Costa Rica has invited tourists to enjoy its natural beauty and used their dollars to conserve it. One of the deepest roots of this ecotourism traces back to a group of American Quakers. They arrived in the 1950s and carved out the community they called Monteverde, or green mountain, a town and cloud forest reserve that form one of the best known tourist spots in this Central American nation. Today, the influence of Quakers can be seen in the produce and food that’s on the grocery store shelves, in the recreation and the Friends school and center, which is a social hub for the larger community of Costa Ricans and settlers. Over time, the number of original Quaker pioneers has dwindled to a relative handful. At Sunday services there is no priest or leader, no sermon, no music, as is typical for many Quaker congregations. It’s called a meeting and mostly conducted in silence.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: For decades Costa Rica has invited tourists to enjoy its natural beauty and used their dollars to conserve it. One of the deepest roots of this ecotourism traces back to a group of American Quakers. They arrived in the 1950s and carved out the community they called Monteverde, or green mountain, a town and cloud forest reserve that form one of the best known tourist spots in this Central American nation. Today, the influence of Quakers can be seen in the produce and food that’s on the grocery store shelves, in the recreation and the Friends school and center, which is a social hub for the larger community of Costa Ricans and settlers. Over time, the number of original Quaker pioneers has dwindled to a relative handful. At Sunday services there is no priest or leader, no sermon, no music, as is typical for many Quaker congregations. It’s called a meeting and mostly conducted in silence.

LUCILLE “LUCKY” GUINDON: The basic tenet, I think, of Quaker faith is the strong belief that there is that of God in every person—that if you sit in silence and listen that you can be led by the spirit…

LUCILLE “LUCKY” GUINDON: The basic tenet, I think, of Quaker faith is the strong belief that there is that of God in every person—that if you sit in silence and listen that you can be led by the spirit…

DE SAM LAZARO: Lucille or “Lucky” Guindon was among the earliest arrivals here, led on an extraordinary journey by another basic tenet of Quaker faith, which goes back to 17th-century England: that’s pacifism.

Newsreel footage “All men between 18 and 25 will be required to register…”

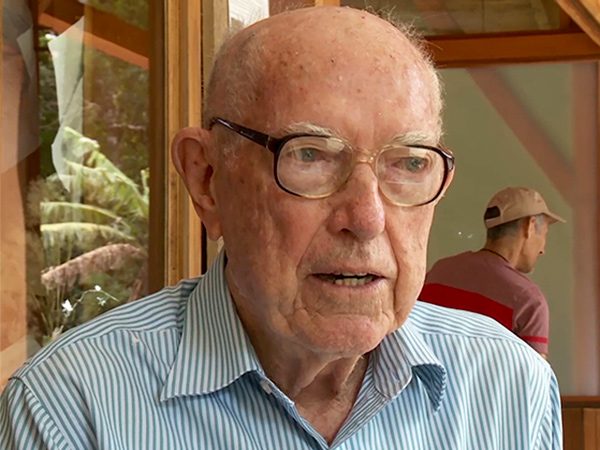

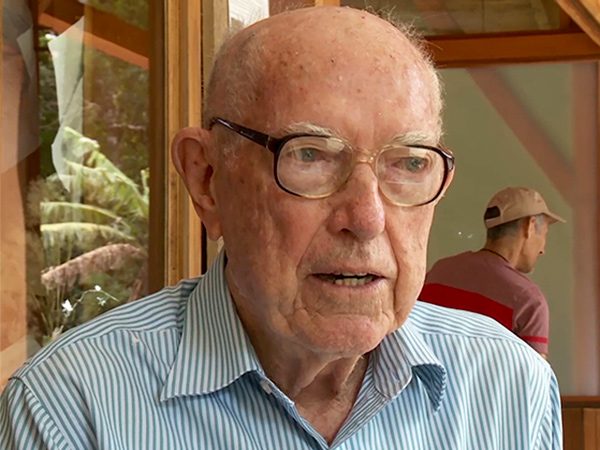

Back in 1948 the US reinstituted the draft, requiring all young men to sign up. Lucky Guindon’s husband, Wolf, resisted. When we visited, Wolf Guindon was in poor health and unable to speak. He died just four weeks later. Another resister from Alabama, Marvin Rockwell, now 93, said they were willing to face the consequences.

MARVIN ROCKWELL: We were arrested and sentenced to a year and a day in prison. We were actually in prison for a third of the sentence, out on parole the balance.

DE SAM LAZAARO: Far more influential than prison was a piece of advice given to them at sentencing by the judge in that Alabama court:

GUINDON: He said, “If you can’t obey the laws of this country, then you should look for another one.” So that planted a seed.

DE SAM LAZARO: Rockwell, Guindon, and two other resisters joined by other families from Fairhope, Alabama—44 people in all—decided to find a new country, unable to reconcile their beliefs with a system that they believed was preparing the nation for the next war. Costa Rica was a natural fit. It was encouraging immigration and, in 1949, abolished its army.

DE SAM LAZARO: Rockwell, Guindon, and two other resisters joined by other families from Fairhope, Alabama—44 people in all—decided to find a new country, unable to reconcile their beliefs with a system that they believed was preparing the nation for the next war. Costa Rica was a natural fit. It was encouraging immigration and, in 1949, abolished its army.

GUINDON: It was also a country with mostly middle class, not the extreme rich and the extreme poor, and they were also welcoming people to come in and help develop it. So my husband, then not my husband, my husband-to-be, wrote to me because we were not together and how would i like to live in Costa Rica? Of course!

DE SAM LAZARO: You grew up in Iowa?

GUINDON: I grew up in Iowa.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Costa Rica they chose to live in could not be more different than Iowa—or Alabama. With proceeds from the sale of land back home, they purchased some 3400 acres in a lush tropical mountainscape. The road here, treacherous even today. Well, they had to build it.

GUINDON: The roads when we first came here was just an ox cart trail. You had to have four-wheel drive, chains, maybe carry an extra axle with you and have a winch. Because you had many places where you’d get stuck, and even then sometimes people had to get pulled out by oxen.

GUINDON: The roads when we first came here was just an ox cart trail. You had to have four-wheel drive, chains, maybe carry an extra axle with you and have a winch. Because you had many places where you’d get stuck, and even then sometimes people had to get pulled out by oxen.

DE SAM LAZARO: There was no clinic. The community counted on faith and, ironically, the military experience of Marvin Rockwell.

ROCKWELL: In the Second World War, I was drafted and wouldn’t carry a rifle, so they put me in the medical corps, which—the training I got was very valuable here because when we first got here, the closest doctor was in Ipuntarena, six hours away by jeep.

DE SAM LAZARO: In time a school and community center were built. Land was cleared and farms established. The Guindons went on to have nine children. Their dairy farm is now operated by son, Benito Guindon.

Together, international conservation groups and the Quaker community, led by Wolf Guindon, agreed to protect the forest from mining, logging, or even further human encroachment.

GUINDON: Wolf spent the first 20 years of his life cutting down trees and the rest of his life saving trees.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Quakers themselves contributed a third of the 3400 acres of land they’d purchased earlier toward the cloud forest reserve. Today some 250,000 ecotourists visit here each year. A smaller number of North Americans have come and stayed. Hawaii native Nicollette Smith settled here with her husband Randall.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Quakers themselves contributed a third of the 3400 acres of land they’d purchased earlier toward the cloud forest reserve. Today some 250,000 ecotourists visit here each year. A smaller number of North Americans have come and stayed. Hawaii native Nicollette Smith settled here with her husband Randall.

NICOLETTE SMITH: It didn’t take long for us to discover it was the perfect place to have kids. I mean, they’re growing up in a lot of ways like I did in Hilo, a small town where everyone knows who you are.

DE SAM LAZARO: For the Smiths, the Friends school and center quickly became a social hub to meet others—a place for cultural events as well as religious observances. Many of those who attend Sunday services are not Quaker.

GUINDON: We’re not out to convert anybody. There are branches of Quakerism where that’s what they do, but not our branch, and so live peaceably to work with and to live cooperatively.

DE SAM LAZARO: While Quakers draw on biblical scriptures, their belief system is inherently ecumenical. Founded amid religious turmoil in 17th century England, Quakerism’s founders believed in direct communion with God, although some branches do have programmed services with Bible readings. After months of attending for mostly social reasons, the Smiths decided to do so for spiritual ones and become Quakers.

DE SAM LAZARO: While Quakers draw on biblical scriptures, their belief system is inherently ecumenical. Founded amid religious turmoil in 17th century England, Quakerism’s founders believed in direct communion with God, although some branches do have programmed services with Bible readings. After months of attending for mostly social reasons, the Smiths decided to do so for spiritual ones and become Quakers.

RANDALL SMITH: I was looking for a place where I could practice empathy, I’m looking for a place to practice tolerance. I’m looking for a place to practice compassion, love, truth. What I found in the Friends community is a place to do that that is safe, that is a very large tent. Now, the great part of that is I ended up joining the most unorganized organized religion I could find.

DE SAM LAZARO: One whose adherents—numbering just a few dozen—have left a large civic footprint in Costa Rica, long known as one of the most peaceful nations in this hemisphere.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Monteverde, Costa Rica.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: For decades Costa Rica has invited tourists to enjoy its natural beauty and used their dollars to conserve it. One of the deepest roots of this ecotourism traces back to a group of American Quakers. They arrived in the 1950s and carved out the community they called Monteverde, or green mountain, a town and cloud forest reserve that form one of the best known tourist spots in this Central American nation. Today, the influence of Quakers can be seen in the produce and food that’s on the grocery store shelves, in the recreation and the Friends school and center, which is a social hub for the larger community of Costa Ricans and settlers. Over time, the number of original Quaker pioneers has dwindled to a relative handful. At Sunday services there is no priest or leader, no sermon, no music, as is typical for many Quaker congregations. It’s called a meeting and mostly conducted in silence.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: For decades Costa Rica has invited tourists to enjoy its natural beauty and used their dollars to conserve it. One of the deepest roots of this ecotourism traces back to a group of American Quakers. They arrived in the 1950s and carved out the community they called Monteverde, or green mountain, a town and cloud forest reserve that form one of the best known tourist spots in this Central American nation. Today, the influence of Quakers can be seen in the produce and food that’s on the grocery store shelves, in the recreation and the Friends school and center, which is a social hub for the larger community of Costa Ricans and settlers. Over time, the number of original Quaker pioneers has dwindled to a relative handful. At Sunday services there is no priest or leader, no sermon, no music, as is typical for many Quaker congregations. It’s called a meeting and mostly conducted in silence. LUCILLE “LUCKY” GUINDON: The basic tenet, I think, of Quaker faith is the strong belief that there is that of God in every person—that if you sit in silence and listen that you can be led by the spirit…

LUCILLE “LUCKY” GUINDON: The basic tenet, I think, of Quaker faith is the strong belief that there is that of God in every person—that if you sit in silence and listen that you can be led by the spirit… DE SAM LAZARO: Rockwell, Guindon, and two other resisters joined by other families from Fairhope, Alabama—44 people in all—decided to find a new country, unable to reconcile their beliefs with a system that they believed was preparing the nation for the next war. Costa Rica was a natural fit. It was encouraging immigration and, in 1949, abolished its army.

DE SAM LAZARO: Rockwell, Guindon, and two other resisters joined by other families from Fairhope, Alabama—44 people in all—decided to find a new country, unable to reconcile their beliefs with a system that they believed was preparing the nation for the next war. Costa Rica was a natural fit. It was encouraging immigration and, in 1949, abolished its army. GUINDON: The roads when we first came here was just an ox cart trail. You had to have four-wheel drive, chains, maybe carry an extra axle with you and have a winch. Because you had many places where you’d get stuck, and even then sometimes people had to get pulled out by oxen.

GUINDON: The roads when we first came here was just an ox cart trail. You had to have four-wheel drive, chains, maybe carry an extra axle with you and have a winch. Because you had many places where you’d get stuck, and even then sometimes people had to get pulled out by oxen. DE SAM LAZARO: The Quakers themselves contributed a third of the 3400 acres of land they’d purchased earlier toward the cloud forest reserve. Today some 250,000 ecotourists visit here each year. A smaller number of North Americans have come and stayed. Hawaii native Nicollette Smith settled here with her husband Randall.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Quakers themselves contributed a third of the 3400 acres of land they’d purchased earlier toward the cloud forest reserve. Today some 250,000 ecotourists visit here each year. A smaller number of North Americans have come and stayed. Hawaii native Nicollette Smith settled here with her husband Randall. DE SAM LAZARO: While Quakers draw on biblical scriptures, their belief system is inherently ecumenical. Founded amid religious turmoil in 17th century England, Quakerism’s founders believed in direct communion with God, although some branches do have programmed services with Bible readings. After months of attending for mostly social reasons, the Smiths decided to do so for spiritual ones and become Quakers.

DE SAM LAZARO: While Quakers draw on biblical scriptures, their belief system is inherently ecumenical. Founded amid religious turmoil in 17th century England, Quakerism’s founders believed in direct communion with God, although some branches do have programmed services with Bible readings. After months of attending for mostly social reasons, the Smiths decided to do so for spiritual ones and become Quakers.