DAVID TERESHCHUK: The Amish community of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania calls it “The Happening.” It took place on October 2, 2006, when the quiet village of Nickel Mines suffered one of America’s most sickening mass shootings. A local milk-truck driver named Charlie Roberts entered an Amish schoolhouse with an arsenal of weaponry. He let the boys and the teacher go but tied up and then shot 10 girls, killing five of them and seriously wounding the other five—and killed himself as police stormed the building.

DAVID TERESHCHUK: The Amish community of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania calls it “The Happening.” It took place on October 2, 2006, when the quiet village of Nickel Mines suffered one of America’s most sickening mass shootings. A local milk-truck driver named Charlie Roberts entered an Amish schoolhouse with an arsenal of weaponry. He let the boys and the teacher go but tied up and then shot 10 girls, killing five of them and seriously wounding the other five—and killed himself as police stormed the building.

PASTOR SAM SMUCKER (Lancaster Worship Center): That was such a horrific event for this area, and for somebody to do that to Amish students, who are known to be people that aren’t—they aren’t acquainted with violence at all and are very peaceful people. So for that happen in an Amish school is just unbelievable. Nobody could believe it.

TERESHCHUK: These five small trees commemorate the five girls killed, between the ages of 7 and thirteen. A decade later the ripple effect of their deaths has been felt not only among the Amish but also in the community at large as well.

TERRI ROBERTS: I would wake up and the tears would actually be streaming from my eyes before I had a conscious thought.

TERRI ROBERTS: I would wake up and the tears would actually be streaming from my eyes before I had a conscious thought.

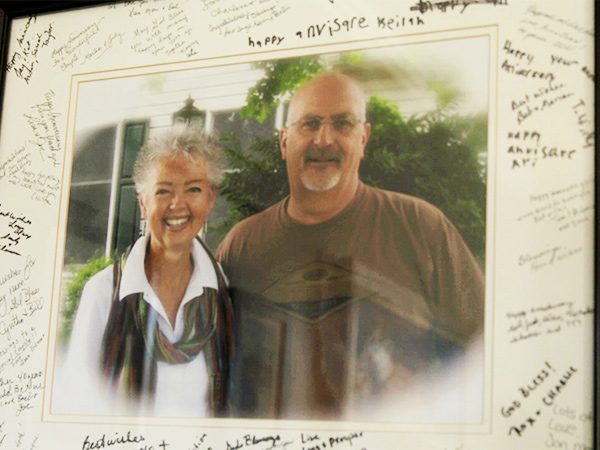

TERESHCHUK: Terri Roberts was among the many people affected forever by the killings. She’s the mother of the killer, Charlie Roberts—not Amish, but a devout Christian who raised her children to be Christian, too. On the day of the shootings, she believed her son might have gone to the school to help in some way and was worried he himself might have been shot by the killer.

ROBERTS: The state trooper and my husband were standing right before me. And I looked at the trooper, and I said, “Is my son alive?” “No ma’am.” And then I looked at my husband, and he said, “It was Charlie. He killed those girls.” No! This, this, this could not be true.

TERESHCHUK: Back at their own home, still in shock, Terri and her husband, Chuck, had a visitor from among the Amish.

R OBERTS: All day long my husband could not lift his head. And he would keep repeating “those poor women, those poor children, the poor parents, the poor fathers. We are going to have to move far away from here. We will never be able to face our Amish neighbors again.” But on Day One, a knock came on the door, and it was Henry our Amish neighbor from across the street. Henry walked over to my husband and just started massaging his shoulders and says, “Roberts, we love you. We don’t hold anything against you. We want you as our neighbor.”

OBERTS: All day long my husband could not lift his head. And he would keep repeating “those poor women, those poor children, the poor parents, the poor fathers. We are going to have to move far away from here. We will never be able to face our Amish neighbors again.” But on Day One, a knock came on the door, and it was Henry our Amish neighbor from across the street. Henry walked over to my husband and just started massaging his shoulders and says, “Roberts, we love you. We don’t hold anything against you. We want you as our neighbor.”

TERESHCHUK: Since that day Terri has had a special label for her neighbor.

ROBERTS: I call Henry “my angel in black,” and the Amish wear all black garb, but he was my angel in black that day, just with his acceptance and his love and this message of forgiveness.

TERESHCHUK: Forgiveness and acceptance were amplified in the days that followed. There were massively-attended funerals for the five dead girls. There was also, of course, a burial for Terri’s son, the killer—an event full of dread for the family, as it inevitably attracted intense media attention. And then the bereaved Amish parents turned up for the Roberts funeral.

ROBERTS: Walking on the grass over toward the area where our son would be buried and just to see this procession of parents coming out and surrounding us was—there just aren’t words  to describe. It was a protective circle against all those media trucks out on the big street that had their big telescoping lenses, and yet here we were. It just felt secure.

to describe. It was a protective circle against all those media trucks out on the big street that had their big telescoping lenses, and yet here we were. It just felt secure.

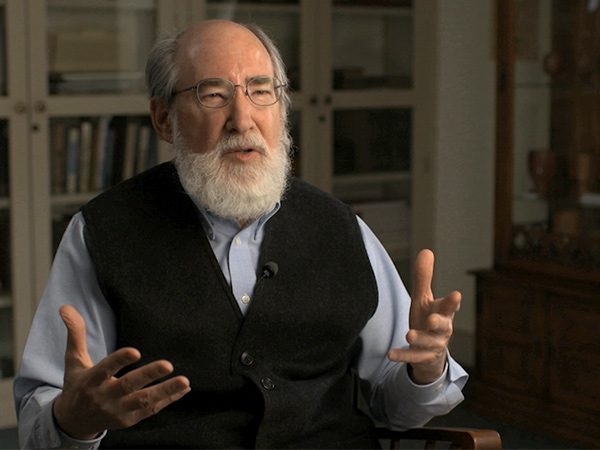

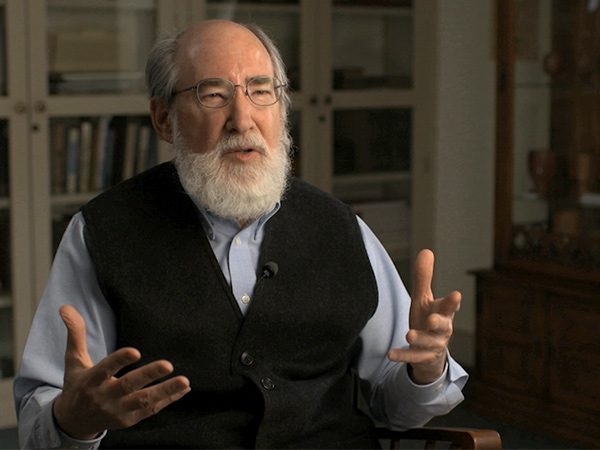

TERESHCHUK: The Amish are known for living apart from the modern world, shunning much technology and rarely, if ever, publicizing their community’s affairs. At Pennsylvania’s Elizabethtown College, Donald Kraybill studies Anabaptist faith groups, which include the Amish.

PROFESSOR DONALD KRAYBILL (Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College): News reporters would ask me, “Well, were the Amish prepared for this? Do they have emergency preparedness drills in their schools?” Well, no, they don’t, but they had forgiveness preparedness. They were ready to respond when events like this come. The Amish response at Nickel Mines was not robotic. It was quick, but that doesn’t mean it was thoughtless, doesn’t mean it was easy. But they knew it was the right thing to do.

TERESHCHUK: Amish forgiveness was seen as striking in the shooting’s immediate aftermath. But it has also extended over time and taken very practical forms. Huge cash donations flooded in to help families of the murdered and injured children. Some of the money, though, was deliberately channeled by the Amish to the killer’s widow and children. They decided to move away from the area.

TERESHCHUK: Amish forgiveness was seen as striking in the shooting’s immediate aftermath. But it has also extended over time and taken very practical forms. Huge cash donations flooded in to help families of the murdered and injured children. Some of the money, though, was deliberately channeled by the Amish to the killer’s widow and children. They decided to move away from the area.

KRAYBILL: I spoke to a father who lost a daughter in the schoolhouse, and I said to him, I said, “Abner,” I said, “how would you define forgiveness?” “Well,” he said, “for me it’s giving up my right to revenge.”

TERESHCHUK: In Terri Roberts’ case, Amish forgiveness has continued in a very tangible way as she and her husband have remained in the same home. It now has a sunroom—a gift from Amish builders.

ROBERTS: Wow. That really was so instrumental in my healing, just to know that that love was poured out for us. And I have such a room of contentment and peace and calm to come into every day.

ROBERTS: Wow. That really was so instrumental in my healing, just to know that that love was poured out for us. And I have such a room of contentment and peace and calm to come into every day.

TERESHCHUK: Peace and calm have become even more important now, since Terri has cancer that is late-stage and has taken over much of her body. But she has been more than a recipient of kindness from the Amish. She has held tea parties in this sunroom for local Amish women, and until the surviving girls and their friends grew up there were often children’s parties in her yard as well. She devotes special attention to one surviving but badly injured girl.

ROBERTS: Five of them survived, but Rosanna is still tube-fed and in a wheelchair. I went to Rosanna’s house every week on Thursday nights, and I would rock her and sing to her and help to bathe her. She’s 15, and now so I don’t hold her anymore, but she’s a beautiful young woman. I feel tears in my eyes now, because it’s just incredible that this child now comes to visit me, and then she came again in December when all the families came in a yellow school bus and sang Christmas carols to me.

TERESHCHUK: At the local nondenominational Worship Center, there’s been much reflection on the past decade, especially from its lead minister. Pastor Smucker says the population in general has benefited from this example of Amish grace.

TERESHCHUK: At the local nondenominational Worship Center, there’s been much reflection on the past decade, especially from its lead minister. Pastor Smucker says the population in general has benefited from this example of Amish grace.

SMUCKER: Everything is coming from a peaceful standpoint, and that’s how they responded. It was amazing. And the whole community saw that and in turn responded with them, so to speak.

TERESHCHUK: For the college chronicler of Amish life and belief, the Roberts family’s singular experience has proved a powerful instance of healing compassion being driven by religious conviction.

KRAYBILL: One Amish father told me, “The Roberts family had a much heavier burden than we did. They have to bear this, the shame and the stigma. We wanted to reach out to them because we care about them.”

TERESHCHUK: And for Terri Roberts herself, her life over the decade since “The Happening” has led her to take stock deeply and afresh.

ROBERTS: I guess every day I wake up with the question how many days yet do I have left on this earth because of stage-four cancer? I mean, this is nearly 10 years after the tragedy, and here I am. I’m alive and I am able to move forward because of the response of the Amish, because of forgiveness. I believe that so much light has been brought into such a dark place.

TERESHCHUK: For Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, this is David Tereshchuk in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

DAVID TERESHCHUK: The Amish community of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania calls it “The Happening.” It took place on October 2, 2006, when the quiet village of Nickel Mines suffered one of America’s most sickening mass shootings. A local milk-truck driver named Charlie Roberts entered an Amish schoolhouse with an arsenal of weaponry. He let the boys and the teacher go but tied up and then shot 10 girls, killing five of them and seriously wounding the other five—and killed himself as police stormed the building.

DAVID TERESHCHUK: The Amish community of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania calls it “The Happening.” It took place on October 2, 2006, when the quiet village of Nickel Mines suffered one of America’s most sickening mass shootings. A local milk-truck driver named Charlie Roberts entered an Amish schoolhouse with an arsenal of weaponry. He let the boys and the teacher go but tied up and then shot 10 girls, killing five of them and seriously wounding the other five—and killed himself as police stormed the building. TERRI ROBERTS: I would wake up and the tears would actually be streaming from my eyes before I had a conscious thought.

TERRI ROBERTS: I would wake up and the tears would actually be streaming from my eyes before I had a conscious thought. OBERTS: All day long my husband could not lift his head. And he would keep repeating “those poor women, those poor children, the poor parents, the poor fathers. We are going to have to move far away from here. We will never be able to face our Amish neighbors again.” But on Day One, a knock came on the door, and it was Henry our Amish neighbor from across the street. Henry walked over to my husband and just started massaging his shoulders and says, “Roberts, we love you. We don’t hold anything against you. We want you as our neighbor.”

OBERTS: All day long my husband could not lift his head. And he would keep repeating “those poor women, those poor children, the poor parents, the poor fathers. We are going to have to move far away from here. We will never be able to face our Amish neighbors again.” But on Day One, a knock came on the door, and it was Henry our Amish neighbor from across the street. Henry walked over to my husband and just started massaging his shoulders and says, “Roberts, we love you. We don’t hold anything against you. We want you as our neighbor.” to describe. It was a protective circle against all those media trucks out on the big street that had their big telescoping lenses, and yet here we were. It just felt secure.

to describe. It was a protective circle against all those media trucks out on the big street that had their big telescoping lenses, and yet here we were. It just felt secure. TERESHCHUK: Amish forgiveness was seen as striking in the shooting’s immediate aftermath. But it has also extended over time and taken very practical forms. Huge cash donations flooded in to help families of the murdered and injured children. Some of the money, though, was deliberately channeled by the Amish to the killer’s widow and children. They decided to move away from the area.

TERESHCHUK: Amish forgiveness was seen as striking in the shooting’s immediate aftermath. But it has also extended over time and taken very practical forms. Huge cash donations flooded in to help families of the murdered and injured children. Some of the money, though, was deliberately channeled by the Amish to the killer’s widow and children. They decided to move away from the area. ROBERTS: Wow. That really was so instrumental in my healing, just to know that that love was poured out for us. And I have such a room of contentment and peace and calm to come into every day.

ROBERTS: Wow. That really was so instrumental in my healing, just to know that that love was poured out for us. And I have such a room of contentment and peace and calm to come into every day. TERESHCHUK: At the local nondenominational Worship Center, there’s been much reflection on the past decade, especially from its lead minister. Pastor Smucker says the population in general has benefited from this example of Amish grace.

TERESHCHUK: At the local nondenominational Worship Center, there’s been much reflection on the past decade, especially from its lead minister. Pastor Smucker says the population in general has benefited from this example of Amish grace.