LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: The Chapel of the Transfiguration is one of the treasures of Grand Teton National Park. For millions of people from all over creation, this is what the Irish call a thin space, where the physical and spiritual worlds intersect.

LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: The Chapel of the Transfiguration is one of the treasures of Grand Teton National Park. For millions of people from all over creation, this is what the Irish call a thin space, where the physical and spiritual worlds intersect.

Singing “Amazing Grace”: “I once was lost, but now I’m found. Was blind but now I see.”

It’s a Sunday morning. Somehow, “Amazing Grace” could not be more appropriate.

Amazing how many people come to places like this to find themselves. Away from the bustle. No need for a sound track. No need for a man-made edifice.

There are 58 national parks. Yellowstone is the granddaddy of them all. Dan Wenk is the superintendent.

DAN WENK: I’ll call it emotional renewal. But I think for everybody it can be something different, and I think they can find their place in this environment to recapture something that maybe they've lost.

RACHEL LOWRY: We’d absolutely miss it. It’s good for your soul to be out here in the wild, out in nature.

RACHEL LOWRY: We’d absolutely miss it. It’s good for your soul to be out here in the wild, out in nature.

LORRAINE SPICER: Well, I just came here because I wanted to see Old Faithful. But I didn’t have any spiritual feelings behind it, no.

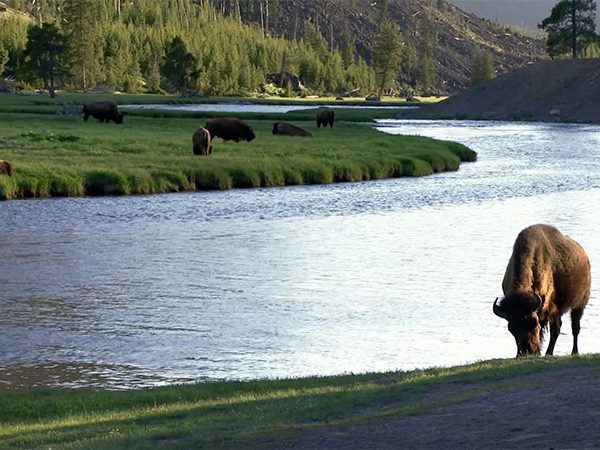

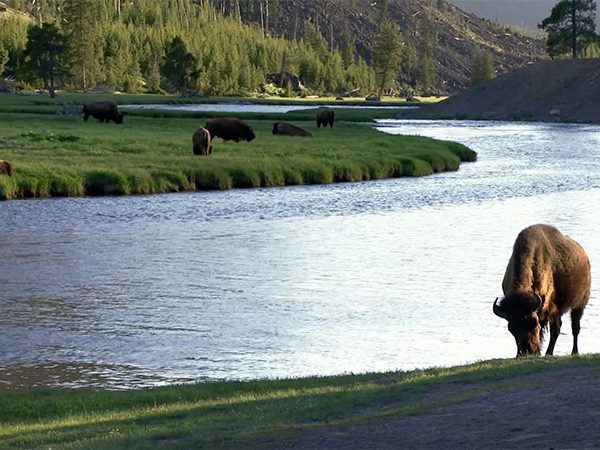

SEVERSON: They come to Yellowstone for the 10,000 thermal pots and especially for Old Faithful, but they usually come back for the animals.

SPICER: We did see a big bison right next to our car. He was humongous. He was three times the size of our car. He was right on the road.

SEVERSON: Many visitors seem to have lost their fear of wild things, like black bears, until the bears start running in their direction. It is conflicts like these between the animals and humans that give park rangers nightmares. The bigger worry, though, is the press of the crowds. There were over four million visitors last year.

“And if the mothers get scared, if they feel their babies are threatened they will trample you. And I don’t mean one little kick!”

SEVERSON: As important as Yellowstone has become to who we are, it is increasingly in jeopardy—in part because it is so popular. 2015 was a record year. This year attendance is up another 15 percent. Meanwhile Congress has been stingy with the funding. Just to repair and maintain the infrastructure in Yellowstone would cost at least a half a billion dollars, probably more, so something’s got to give.

Superintendent Wenk says one solution may require that visitors make reservations in order to visit the park. Another, already in place in some parks, allows entry only aboard park buses.

Superintendent Wenk says one solution may require that visitors make reservations in order to visit the park. Another, already in place in some parks, allows entry only aboard park buses.

WENK: The core of what we do—if we don't protect this place we’ve failed our mission. We'll never get back the thermal features, or the wildlife, or some of the natural features if we don't make sure we're making the right decisions every day.

SEVERSON: There’s probably not a soul alive who knows Yellowstone better than photographer Tom Murphy. His work has appeared in National Geographic and the New York Times. He figures he’s spent 3500 days taking pictures of Yellowstone and its critters. You will find very few people devoted—some might say crazy—enough to crisscross an area bigger than Rhode Island and Delaware in the middle of the winter.

SEVERSON: Tom stresses patience and serendipity. He stood in -35 degree temperatures for three hours to get this shot.

TOM MURPHY: My definition of God is the force of life, whatever that is, whatever level, from the bacteria on my hands to me, to giraffes, to that tree. That's God. So there's a continuity, there's a power, there's an interrelatedness to this whole world because of this force of life—whatever that is.

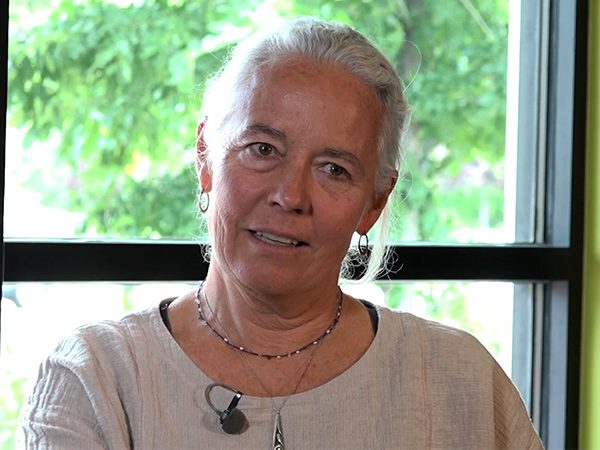

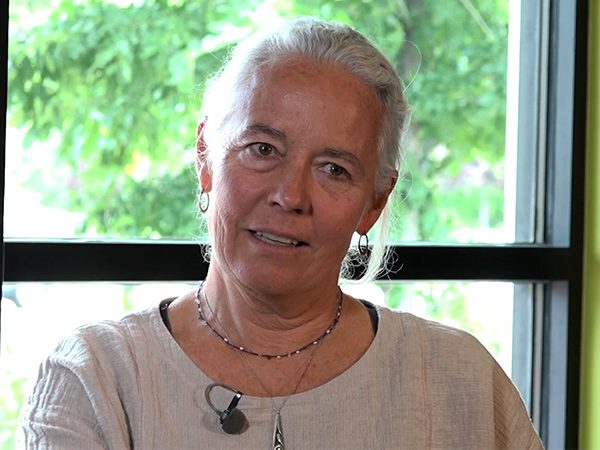

CAROLINE BYRD: Wildness does something to me. It feeds me in a way that being away from it I miss it. It’s this tangible sense of an intact place where all the pieces are working.

SEVERSON: Caroline Byrd fell in love with Yellowstone the first minute she came here. Now she is the executive director of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition.

The problem as she sees it is that the boundaries of Yellowstone were drawn up to meet the demands of man rather than the demands of nature. In other words, grizzly bears can’t read boundary markers. She particularly loves the grizzlies

BYRD: Grizzlies do represent the wildness of greater Yellowstone. They are massively powerful and majestic as well as really smart—there’s something about them that’s so both awesome and dangerous.

BYRD: Grizzlies do represent the wildness of greater Yellowstone. They are massively powerful and majestic as well as really smart—there’s something about them that’s so both awesome and dangerous.

SEVERSON: And because of climate change, grizzlies are venturing more into human spaces, and that can be both dangerous and rewarding. Rewarding for those who catch a glimpse of animals in the wild.

BYRD: People find those sacred moments. They’re experiencing and having this connection to wild nature that they get nowhere else. And it is a pilgrimage.

JIM SMITH: There is a certain peace, and it touches you right to your soul, and it heals a lot of things.

SEVERSON: When we found Jim Smith he’d been here a month, his first visit. He is transfixed by the wildlife he found here.

SEVERSON: When we found Jim Smith he’d been here a month, his first visit. He is transfixed by the wildlife he found here.

SMITH: I’ve been asking, why is the wilderness so important? It’s a part of us. We have to have it. It’s part of our primitive roots. The people need that, especially people who live mostly and work in the cities, I think. They are still drawn back, yeah, like I was.

SEVERSON: He says the experience for him has been transformative.

SMITH: By all rights we shouldn’t really even be here, you know. We should back out, tear out the roads, and leave it. But at the same time humanity needs this. People do need this badly. I think the most important thing I’ve learned from other people is that they feel at peace here.

WENK: We have to really help people understand what Yellowstone does, and if they do understand I believe they'll fight to protect it. And I think Congress will fund it, because people will demand that they fund it.

SEVERSON: Have you seen any wildlife, any animals?

SEVERSON: Have you seen any wildlife, any animals?

JENNIFER DIBBLE: We have. Just up the road we saw a bison.

SEVERSON: So what did you think of the bison?

CHILD: It’s big!

SEVERSON: For George and Jennifer Dibble, Yellowstone is a classroom for their three kids to learn that God is still out there.

DIBBLE: Yellowstone is showing you how creation is going on and on and on—that life, the cycles are still continuing, and we get to come and show our kids that. I love the fact that we can bring our kids here.

BYRD: It is a religious moment, a sacred moment that takes us all back to a place that you don’t get to see in most of the civilized world.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Lucky Severson in Yellowstone National Park

LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: The

LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: The  RACHEL LOWRY: We’d absolutely miss it. It’s good for your soul to be out here in the wild, out in nature.

RACHEL LOWRY: We’d absolutely miss it. It’s good for your soul to be out here in the wild, out in nature. Superintendent Wenk says one solution may require that visitors make reservations in order to visit the park. Another, already in place in some parks, allows entry only aboard park buses.

Superintendent Wenk says one solution may require that visitors make reservations in order to visit the park. Another, already in place in some parks, allows entry only aboard park buses.

BYRD: Grizzlies do represent the wildness of greater Yellowstone. They are massively powerful and majestic as well as really smart—there’s something about them that’s so both awesome and dangerous.

BYRD: Grizzlies do represent the wildness of greater Yellowstone. They are massively powerful and majestic as well as really smart—there’s something about them that’s so both awesome and dangerous. SEVERSON: When we found Jim Smith he’d been here a month, his first visit. He is transfixed by the wildlife he found here.

SEVERSON: When we found Jim Smith he’d been here a month, his first visit. He is transfixed by the wildlife he found here. SEVERSON: Have you seen any wildlife, any animals?

SEVERSON: Have you seen any wildlife, any animals?