Daniel A. Morris: Love, Justice, and the Trump Victory

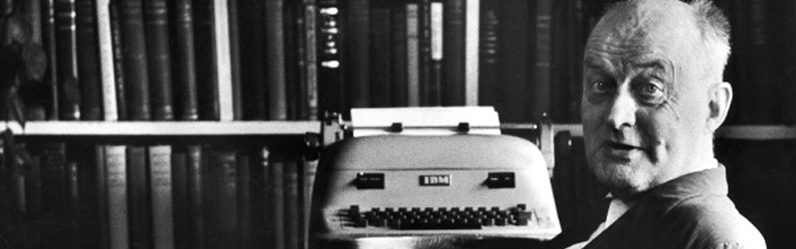

“Any justice which is only justice soon degenerates into something less than justice. It must be saved by something which is more than justice.”—Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study of Ethics and Politics by Reinhold Niebuhr

“In so far as justice admits the claims of the self, it is something less than love. Yet it cannot exist without love and remain justice. For without the ‘grace’ of love, justice always degenerates into something less than justice.”—Love and Justice: Selections from the Shorter Writings of Reinhold Niebuhr (edited by D.B. Robertson)

Reinhold Niebuhr warned us about this moment. His Christian reflection on love and justice anticipated the violence and injustice we are seeing right now, after the presidential election. And while Niebuhr’s reflections are of limited value when it comes to race, we should all carefully heed his words about how love both negates and fulfills justice.

Niebuhr believed that love and justice have a complicated relationship with each other. Love—the virtue that inclines people to genuinely wish each other well for their own sakes, to sacrifice for each other, to show affection to each other, etc.—is the highest moral ideal that we can know. Niebuhr called it the “impossible possibility” because he thought we can never really fully love each other without some measure of self-interest marring the relationship. And yet, this impossible ideal could technically be possible given our abilities to transcend our own experiences and to know God’s love, however limited those abilities might be.

This moral ideal is so pure that it relativizes every accomplishment of justice in human political life. Justice—the tendency to “render unto each their due,” the balancing of competing forms of power, and the proportional navigation of the rights of different groups—is hugely valuable for Niebuhr. But it is also so limited and compromised in relation to love that Niebuhr says love negates justice.

And yet, while love negates justice, love also fulfills justice. Niebuhr argues that we need love to pull us along toward justice. We need whatever limited and relative forms of good will, self-sacrifice, and affection we can find as we pursue justice together in a volatile social and political climate. When Niebuhr says that love fulfills justice, he is saying that love will allow us to care for each other and protect each other while we try to balance our competing powers and claims. Absent love’s influence, our pursuits of justice can go horribly wrong. “Any justice which is only justice,” Niebuhr writes, “soon degenerates into something less than justice.” Here is the warning we desperately need to hear today. Without love, our pursuits of justice may lapse into violent vengeance.

This warning is playing out before our eyes in the aftermath of the presidential election. We are watching concerns for justice degenerate into something more sinister. Trump’s supporters were, in many ways, motivated by the pursuit of justice. There is a legitimate case to be made about the injustice of allowing people who enter the country illegally to continue to live and work in this country (although this case is poorly made when it vilifies poor people and fails to acknowledge business owners’ reliance on immigrant labor). There is a legitimate case to be made that justice requires the state to protect its citizens from threats of terrorism (although this case is poorly made when it leads people to demonize refugees and hate Muslims). There are other legitimate concerns about justice that Trump and his supporters have raised, even if these concerns have not always been raised responsibly.

Such claims to justice are degenerating into something less than justice all across America right now. Trump’s victory has emboldened many people to assault, harass, and intimidate people of color, LGBTQ people, Muslims, and other marginalized people. (Of course, a Trump loss may also have resulted in these forms of violence.) There are widespread reports of racially motivated assault and vandalism by people gloating over Trump’s victory. Latinx citizens in public schools are being mocked by their classmates with taunts of “build the wall,” which stirs traumatic fear of familial separation. Muslim citizens have been told that Trump will send them back to where they came from. These stories are important to hear, and anyone who wants to know more can visit the Twitter feed for “Day 1 in Trump’s America.”

What all these stories show is that, whatever forms of justice may have originally motivated Trump supporters, many of them are engaging in vicious forms of vengeance that threaten the most vulnerable members of our society. Niebuhr predicted this in his reflections on love and justice. These stories of assault, harassment, and vandalism chart the downward spiral of justice into vengeance and indicate a severe deficit of love in civic life.

Justice should lead people to protect and empower the most vulnerable. Although Niebuhr’s work was valuable on this score, it was not perfect. Some writers fault his definitions of sin (as pride) and love (as self-sacrifice) for perpetuating the oppression of marginalized people. This is a valid critique.

It is theologian James Cone’s critique of Niebuhr, however, that bears emphasis right now. In The Cross and the Lynching Tree, Cone expressed legitimate frustration with Niebuhr as a white advocate of racial justice by writing that Niebuhr “was no prophet on race. Prophets take risks and speak out in righteous indignation against society’s mistreatment of the poor, even risking their lives, as we see in the martyrdom of Jesus and Martin King. Niebuhr took no risks for blacks.”

Cone’s words are a reminder to all of us in the aftermath of Trump’s victory. What have those of us with privilege sacrificed for black, Latinx, Muslim, and LGBTQ people? What will white people—regardless of whom we supported in the presidential election—sacrifice right now to protect and empower the most vulnerable among us?