TIM O’BRIEN, correspondent: Much of the growth in the prison population can be traced to the war on drugs that took on steam in the early days of the Reagan Administration.

TIM O’BRIEN, correspondent: Much of the growth in the prison population can be traced to the war on drugs that took on steam in the early days of the Reagan Administration.

Nancy Reagan: Just say no.

O’BRIEN: Congress and the states followed up and passed laws mandating lengthy prison terms for mere possession, including for many young people who themselves posed no threat of violence. The resulting overcrowding gave birth to a private prison industry—driven by lobbyists—with a vested interest in building new prisons. There was also a spike in street crime starting in the late sixties, which helped Richard Nixon win the White House in 1968 and helped Michael Dukakis—portrayed as soft on crime—lose the presidential election twenty years later.

Voice in political ad: Weekend prison passes: Dukakis on crime.

O’BRIEN: Candidates for national office ever since have been hawking their bona fides as crime fighters.

Donald Trump: I am the law and order candidate.

Donald Trump: I am the law and order candidate.

O’BRIEN: While the United States has the highest incarceration rate in the civilized world, here in Dearborn County, Indiana—the “heartland”—they may have the highest incarceration rate in the United States. They send more people to prison here than they do in San Francisco, which has thirteen times as many people. The numbers are a source of pride to county prosecutor, Aaron Negangard:

AARON NEGANGARD (Dearborn County, Indiana Prosecutor): We hold people accountable to the law, and I think that’s the way it should be. And not everybody agrees with that.

O’BRIEN: There’s not much violent crime here. It’s a peaceful community, 97 percent white, that sits along the Ohio River 20 miles west of Cincinnati. But Dearborn County reflects a  phenomenon that is sweeping suburban and rural counties throughout the country—an epidemic of heroin and opioid addiction that cuts across all socio-economic lines:

phenomenon that is sweeping suburban and rural counties throughout the country—an epidemic of heroin and opioid addiction that cuts across all socio-economic lines:

NEGANGARD: There’s nobody in prison who is not dangerous.

O’BRIEN: Somebody—merely possession of drugs—they’re dangerous?

NEGANGARD: If they’re a drug addict. you gotta have a lotta money to support a drug habit. They’re stealing; they’re burglarizing; they’re neglecting their kids, if they have them; they’re operating while impaired. This is going on if you have a drug addict who is not in recovery.

O’BRIEN: Perhaps it is not so surprising so many American are in prison. We also have one of the highest murder rates in the world. Marc Mauer, long-time head of the Sentencing Project, is one of the country’s leading experts on sentencing policy:

MARC MAUER (Executive Director, The Sentencing Project): We do have a higher rate of violence—not crime, but a higher rate of violence—than other industrialized nations. Some of that, our high murder rate, is related to the widespread availability of guns and illegal weapons that are circulating. So if you compare our rate of murder-homicides to other nations, about half the differential between us and those other nations is due to the easy availability of firearms.

MARC MAUER (Executive Director, The Sentencing Project): We do have a higher rate of violence—not crime, but a higher rate of violence—than other industrialized nations. Some of that, our high murder rate, is related to the widespread availability of guns and illegal weapons that are circulating. So if you compare our rate of murder-homicides to other nations, about half the differential between us and those other nations is due to the easy availability of firearms.

O’BRIEN: But it is not just the easy availability of guns that distinguishes America from our European neighbors or explains why our incarceration rate is more than three times higher. Yale law professor James Whitman, in his critically acclaimed book Harsh Justice, says Americans simply do not share the sense of “human dignity” that their forebears historically bestowed, even on those who committed horrible crimes:

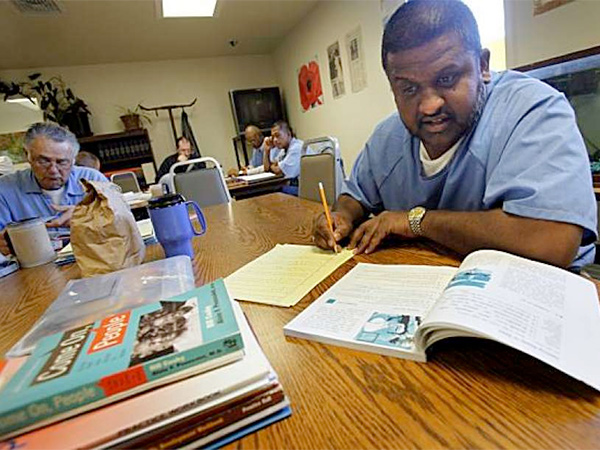

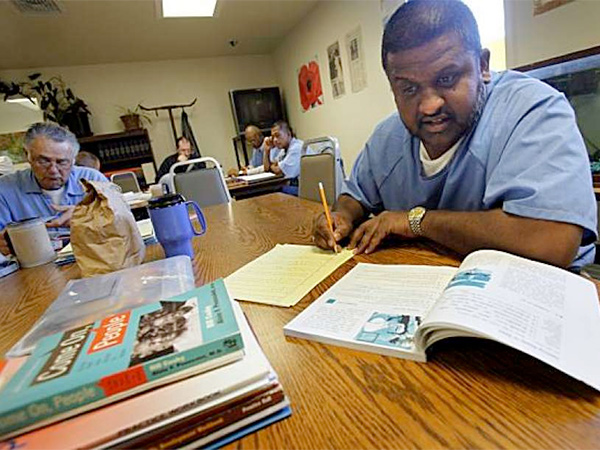

PROFESSOR JAMES WHITMAN (Professor of Comparative and Foreign Law, Yale Law School): If you go back to the 18th century, before the American Revolution, before the French Revolution, what you discover is that there were two tracks of punishment. There was punishment for high-status people, and there was punishment for low-status people. The most famous example involves the death penalty. High-status people had their heads cut off; beheading was the ordinary form of the death penalty for high-status persons. Low-status person were hanged. Hanging was much more shameful than beheading. But it wasn’t only true of the death penalty. Much more broadly, high-status persons were treated respectfully. They were confined in what were called forms of “fortress confinement.” They were placed in apartments where they were given books to read. They had visits from their friends. They could expect fine food and decent treatment, whereas low-status persons were effectively subjected to slavery, a kind of death sentence in itself. What’s happened, remarkably, over the last couple of centuries is that in continental Europe and particularly the old high-status forms of treatment have been generalized to all convicts in Europe, so that everyone is now treated decently.

PROFESSOR JAMES WHITMAN (Professor of Comparative and Foreign Law, Yale Law School): If you go back to the 18th century, before the American Revolution, before the French Revolution, what you discover is that there were two tracks of punishment. There was punishment for high-status people, and there was punishment for low-status people. The most famous example involves the death penalty. High-status people had their heads cut off; beheading was the ordinary form of the death penalty for high-status persons. Low-status person were hanged. Hanging was much more shameful than beheading. But it wasn’t only true of the death penalty. Much more broadly, high-status persons were treated respectfully. They were confined in what were called forms of “fortress confinement.” They were placed in apartments where they were given books to read. They had visits from their friends. They could expect fine food and decent treatment, whereas low-status persons were effectively subjected to slavery, a kind of death sentence in itself. What’s happened, remarkably, over the last couple of centuries is that in continental Europe and particularly the old high-status forms of treatment have been generalized to all convicts in Europe, so that everyone is now treated decently.

We saw this most recently in the case involving Anders Breivik, the horrific mass murderer in Norway...

O’BRIEN: Anders Breivik, a self

-proclaimed neo-Nazi, murdered seventy-seven people in two separate attacks in Norway in 2011.

PROFESSOR WHITMAN: …who, as you may have read, is being housed in a three-room apartment with all sorts of conveniences and equipment. That sort of treatment—even a man who committed an extraordinarily horrific act of that type is considered necessary for maintaining values of human dignity in Europe. By contrast, the old high-status forms of treatment have entirely vanished in the United States. As we all know, detention in an American prison is an extraordinarily degrading experience.

O’BRIEN: What about retribution?

NEGANGARD: Well, I’ll tell you, I think retribution—honestly, in the last analysis—is for the good Lord and not the American government.

O’BRIEN: That might be a tough sell for many Americans who cite retribution as the primary reason they support capital punishment. In most of Europe, which doesn’t have the death penalty, only the most dangerous offenders go to prison, and rehabilitation is a high priority. In the United States, by contrast, the primary goals seem to be retribution and deterrence. To Marc Mauer, it is a case of limited resources, aggravated by mistaken priorities.

MAUER: If we reverse priorities, scale back the use of prison that would free up enormous resources—first, to invest in prevention and treatment for teenagers, the 14-15 and 16-year-olds who are beginning to get into trouble. That’s the time we need to be intervening. For those adults who don’t need to be in prison, then we need to supervise them in the community but address the underlying issues that got them there. So if it’s poor education, if its substance abuse, if it’s mental health issues, that’s where we need to provide the treatment, the services they need—not because it’s a liberal do-gooder thing to do. Because it’s the right thing to do, and it is more likely to prevent crime in the future.

O’BRIEN: But does the current practice of sending criminals away for lengthy prison terms, as they do in Dearborn County, Indiana, actually reduce crime? Professor Whitman has no doubts that it does:

PROFESSOR WHITMAN: The kind of large-scale detention we have in the U.S. cuts down on violent crime rates. There’s absolutely no doubt about that, and I’ll say that my view is that incarceration certainly ought to be used to protect the general public. Offenders who really present a danger to their fellow citizens have to be kept off the streets. There’s no doubt about that. The great problem in American law though is that we don’t really take serious what that sort of “dangerousness calculus” would require. For example, if we’re really worried about dangerous offenders, there’s no reason to keep them locked up until they’re ninety years old.

PROFESSOR WHITMAN: The kind of large-scale detention we have in the U.S. cuts down on violent crime rates. There’s absolutely no doubt about that, and I’ll say that my view is that incarceration certainly ought to be used to protect the general public. Offenders who really present a danger to their fellow citizens have to be kept off the streets. There’s no doubt about that. The great problem in American law though is that we don’t really take serious what that sort of “dangerousness calculus” would require. For example, if we’re really worried about dangerous offenders, there’s no reason to keep them locked up until they’re ninety years old.

O’BRIEN: Prosecutor Negangard counts among his heroes the Scottish economist Adam Smith, who wrote,“Mercy to the guilty is cruelty to the innocent.” To Professor Whitman and others, it is less about who is being punished than who is doing the punishing:

PROFESSOR WHITMAN: The way a society manages its criminal justice system is a test of the society’s decency. Winston Churchill very famously said that “to know whether you’re dealing with a decent society, you should look first at its criminal justice system.”

O’BRIEN: There does seem to be a developing consensus among liberals and many conservatives that lengthy prison terms, once thought to be a quick fix for violent crime, is neither.

O’BRIEN: There does seem to be a developing consensus among liberals and many conservatives that lengthy prison terms, once thought to be a quick fix for violent crime, is neither.

ANTONIO GINATTA (Advocacy Director, Human Rights Watch US Program): You can see very intelligent and thoughtful representatives from both sides of the aisle talking about the need for sentencing reform, be it for issues related to dignity and humanity and respect for a person’s ability to succeed again after committing a crime. And at the other end of the equation you can talk about people saying it makes no sense economically. It is a bad investment. Continuing to build prisons and continuing to keep people in prison for so long and then getting terrible recidivism rates—it’s a government program that doesn’t work.

O’BRIEN: Yet given America’s apparent thirst for retribution, the crime problem that continues to plague the country and the perception that being tough on crime wins votes, any road to meaningful sentencing reform could be long—and steep.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Tim O’Brien in Washington.

TIM O’BRIEN, correspondent: Much of the growth in the prison population can be traced to the war on drugs that took on steam in the early days of the Reagan Administration.

TIM O’BRIEN, correspondent: Much of the growth in the prison population can be traced to the war on drugs that took on steam in the early days of the Reagan Administration. Donald Trump: I am the law and order candidate.

Donald Trump: I am the law and order candidate. phenomenon that is sweeping suburban and rural counties throughout the country—an epidemic of heroin and opioid addiction that cuts across all socio-economic lines:

phenomenon that is sweeping suburban and rural counties throughout the country—an epidemic of heroin and opioid addiction that cuts across all socio-economic lines: MARC MAUER (Executive Director, The Sentencing Project): We do have a higher rate of violence—not crime, but a higher rate of violence—than other industrialized nations. Some of that, our high murder rate, is related to the widespread availability of guns and illegal weapons that are circulating. So if you compare our rate of murder-homicides to other nations, about half the differential between us and those other nations is due to the easy availability of firearms.

MARC MAUER (Executive Director, The Sentencing Project): We do have a higher rate of violence—not crime, but a higher rate of violence—than other industrialized nations. Some of that, our high murder rate, is related to the widespread availability of guns and illegal weapons that are circulating. So if you compare our rate of murder-homicides to other nations, about half the differential between us and those other nations is due to the easy availability of firearms. PROFESSOR JAMES WHITMAN (Professor of Comparative and Foreign Law, Yale Law School): If you go back to the 18th century, before the American Revolution, before the French Revolution, what you discover is that there were two tracks of punishment. There was punishment for high-status people, and there was punishment for low-status people. The most famous example involves the death penalty. High-status people had their heads cut off; beheading was the ordinary form of the death penalty for high-status persons. Low-status person were hanged. Hanging was much more shameful than beheading. But it wasn’t only true of the death penalty. Much more broadly, high-status persons were treated respectfully. They were confined in what were called forms of “fortress confinement.” They were placed in apartments where they were given books to read. They had visits from their friends. They could expect fine food and decent treatment, whereas low-status persons were effectively subjected to slavery, a kind of death sentence in itself. What’s happened, remarkably, over the last couple of centuries is that in continental Europe and particularly the old high-status forms of treatment have been generalized to all convicts in Europe, so that everyone is now treated decently.

PROFESSOR JAMES WHITMAN (Professor of Comparative and Foreign Law, Yale Law School): If you go back to the 18th century, before the American Revolution, before the French Revolution, what you discover is that there were two tracks of punishment. There was punishment for high-status people, and there was punishment for low-status people. The most famous example involves the death penalty. High-status people had their heads cut off; beheading was the ordinary form of the death penalty for high-status persons. Low-status person were hanged. Hanging was much more shameful than beheading. But it wasn’t only true of the death penalty. Much more broadly, high-status persons were treated respectfully. They were confined in what were called forms of “fortress confinement.” They were placed in apartments where they were given books to read. They had visits from their friends. They could expect fine food and decent treatment, whereas low-status persons were effectively subjected to slavery, a kind of death sentence in itself. What’s happened, remarkably, over the last couple of centuries is that in continental Europe and particularly the old high-status forms of treatment have been generalized to all convicts in Europe, so that everyone is now treated decently.

PROFESSOR WHITMAN: The kind of large-scale detention we have in the U.S. cuts down on violent crime rates. There’s absolutely no doubt about that, and I’ll say that my view is that incarceration certainly ought to be used to protect the general public. Offenders who really present a danger to their fellow citizens have to be kept off the streets. There’s no doubt about that. The great problem in American law though is that we don’t really take serious what that sort of “dangerousness calculus” would require. For example, if we’re really worried about dangerous offenders, there’s no reason to keep them locked up until they’re ninety years old.

PROFESSOR WHITMAN: The kind of large-scale detention we have in the U.S. cuts down on violent crime rates. There’s absolutely no doubt about that, and I’ll say that my view is that incarceration certainly ought to be used to protect the general public. Offenders who really present a danger to their fellow citizens have to be kept off the streets. There’s no doubt about that. The great problem in American law though is that we don’t really take serious what that sort of “dangerousness calculus” would require. For example, if we’re really worried about dangerous offenders, there’s no reason to keep them locked up until they’re ninety years old. O’BRIEN: There does seem to be a developing consensus among liberals and many conservatives that lengthy prison terms, once thought to be a quick fix for violent crime, is neither.

O’BRIEN: There does seem to be a developing consensus among liberals and many conservatives that lengthy prison terms, once thought to be a quick fix for violent crime, is neither.