Support for this story provided by George Family Foundation.

Monks chanting: “Like incense let my prayer rise before you, O God …”

Monks chanting: “Like incense let my prayer rise before you, O God …”

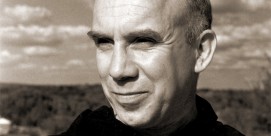

PAULA HUSTON: I was probably in my late thirties at that time, and for the previous 20 years I had been completely away from faith and really felt myself to be an atheist. I don’t think I’d ever even talked to a priest before, much less seen a monk, and here were these monks, and they were dressed in their interesting and strange white robes, and it just struck me so hard that this was really a radically alternative way to live.

KATE OLSON, correspondent: Meeting the monks of New Camaldoli Hermitage for the first time 30 years ago was a life-changing experience for Paula Huston, who taught writing at California State University in San Luis Obispo.

HUSTON: I think I was really struck by the gentleness, the quiet, the kindness. After having gone through a divorce and divorce court, I was used to a much different attitude from people in my life at that point. It was also the first time I had time to look inside of myself—just to confront who was inside. Who was this angry young woman inside? What was I so angry about? What had I been missing for years and years and years? What was I deeply longing for?

OLSON: Perched on the cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean, the hermitage is a popular retreat location. Through their ministry of hospitality, the Camaldolese Benedictines welcome guests to experience their life of contemplation and prayer.

OLSON: Perched on the cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean, the hermitage is a popular retreat location. Through their ministry of hospitality, the Camaldolese Benedictines welcome guests to experience their life of contemplation and prayer.

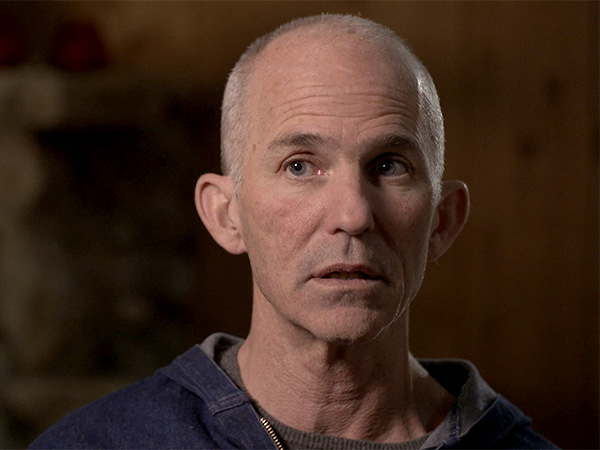

FR CYPRIAN CONSIGLIO, OSB Cam: I think people know intuitively that there’s something missing from their diet.

OLSON: Cyprian Consiglio is the prior at the hermitage.

FR. CYPRIAN: If we’re not rooted in the spiritual, which we believe is actually the deepest part of being human, then we’re not fully alive. And the thing that's really starving is our souls. We keep trying to fill it up on the outside, not realizing that there is this fountain inside.

OLSON: Daily life at the hermitage is guided by a rule for spiritual growth and living in community written 1500 years ago by St. Benedict.

FR CYPRIAN: Benedict really lays the day out for the monk with this beautiful kind of proportion of the day between prayer, work, and study.

OLSON: The monks sustain their way of life through their retreat ministry and contributions from friends. They combine solitude and community, living as hermits in individual cells and gathering for prayer throughout the day.

OLSON: The monks sustain their way of life through their retreat ministry and contributions from friends. They combine solitude and community, living as hermits in individual cells and gathering for prayer throughout the day.

FR CYPRIAN: We stop at several times a day to renew our prayer, so that now I can go to the kitchen again and still keep praying there, and now I can meet with a retreatant and talk to her or him and still be mindful in prayer there, or I can do my work in my office and still be mindful. It’s not about escaping ordinary life. It’s just not. It’s about coming back to ordinary life and realizing, oh, God was in this place, too, and I just didn’t see it before.

OLSON: The monks practice lectio divina, which means sacred reading—listening for the voice of God speaking through scripture or other texts.

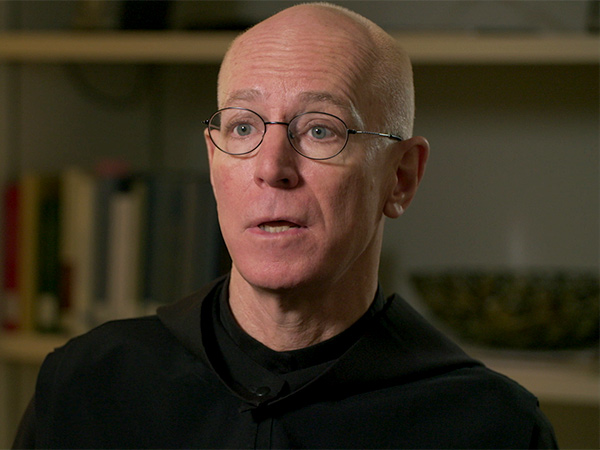

Columba Stewart is a scholar of monasticism and a Benedictine monk at St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota.

FR COLUMBA STEWART (St. John’s Abbey): I’m reminded regularly of how easy it is to repress and suppress what I’m actually feeling about something until it bubbles up in my times of silence and prayer. So I think that is part of what Benedict means by listening with the ear of the heart—of paying attention to what’s inside and what’s operating at depths below the level at which we conduct most of our day-to-day lives.

FR COLUMBA STEWART (St. John’s Abbey): I’m reminded regularly of how easy it is to repress and suppress what I’m actually feeling about something until it bubbles up in my times of silence and prayer. So I think that is part of what Benedict means by listening with the ear of the heart—of paying attention to what’s inside and what’s operating at depths below the level at which we conduct most of our day-to-day lives.

OLSON: Spending time in solitude and silence at the hermitage helped Huston confront the anxiety that had gripped her life since childhood.

HUSTON: I was so busy, so stressed out all the time, always in a rush, never on time, way too many things on my ‘to do’ list. But I found that so many things would get blocked by the fear of something going wrong. I consciously handed that lifetime of anxiety over to God and said I can’t get rid of it on my own, but I’m going to go to bed and not put the wooden spoon in the window. And I slept, and it was like being healed.

OLSON: Longing for a deeper relationship with God, Huston became an oblate of New Camaldoli, adapting the teachings and practice of prayer followed by the monks to her life outside the monastery. Huston prays at home in the morning and evening, and practices lectio divina. And, as St. Benedict recommends, she spends time every day doing physical labor, working on the land. Her writing studio now doubles as a modified cell, where she combines writing and prayer, which has changed how she sees her work.

HUSTON: I used to see what I was doing as my path to the Pulitzer Prize, and that is long gone. Now it’s my way of serving. That’s how it see it.

HUSTON: I used to see what I was doing as my path to the Pulitzer Prize, and that is long gone. Now it’s my way of serving. That’s how it see it.

OLSON: She also discovered that following the Rule, an example of the monks, transformed her relationships with others.

HUSTON: When Mike, my husband, who always struggled with computers, would ask me yet again for help, listening to the tone of my own voice when I would be doing a good deed, but actually sounding impatient, because I was learning from the Rule and from watching the monks that it’s these little ways of behaving with one another, whether we approach someone with genuine warmth and gentleness or whether we stand back in a kind of cool and aloof way—that’s an enormous, it has a huge impact on other people.

Monks praying: “Give us this day ….”

FR COLUMBA: The real dynamic of the Rule is to move from the self to the other. What Benedict is doing is providing a charter for making a community that really endures and that can encompass a variety of people. They’re all there for some purpose that’s really beyond themselves, this spiritual quest, and they recognize they can’t do it by themselves.

FR COLUMBA: The real dynamic of the Rule is to move from the self to the other. What Benedict is doing is providing a charter for making a community that really endures and that can encompass a variety of people. They’re all there for some purpose that’s really beyond themselves, this spiritual quest, and they recognize they can’t do it by themselves.

Paula Huston speaking during lay retreat: And so the Rule has always been about moderation…

OLSON: Having found community at New Camaldoli, Huston teams up with one of the monks to give retreats on Benedictine spirituality and its contemplative approach to life.

FR COLUMBA: What I find interesting as a historian is that, in a sense, we’re going back to where it all began, with a variety of models of Christian ascetic life. And by ascetic I just mean  disciplined, and that’s what people are recovering, and then they’re figuring out ways that they can live that as individuals, as families, as loose associations of friends who find this particular path to be helpful, sustaining, and nourishing to them.

disciplined, and that’s what people are recovering, and then they’re figuring out ways that they can live that as individuals, as families, as loose associations of friends who find this particular path to be helpful, sustaining, and nourishing to them.

OLSON: Whatever new forms arise, the shared commitment of monks and oblates to live by an ancient rule may not only ensure the survival of monasticism, but bring its way of life to a wider world.

FR CYPRIAN: This is a little village. We’re actually living a life with our staff and our friends and our retreatants, besides the inner core of the community of monks, and hopefully we are modeling a way of life, modeling a different way to be in the world.

OLSON: For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Kate Olson reporting from Big Sur, California.

Monks chanting: “Like incense let my prayer rise before you, O God …”

Monks chanting: “Like incense let my prayer rise before you, O God …”  OLSON: Perched on the cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean, the hermitage is a popular retreat location. Through their ministry of hospitality, the Camaldolese Benedictines welcome guests to experience their life of contemplation and prayer.

OLSON: Perched on the cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean, the hermitage is a popular retreat location. Through their ministry of hospitality, the Camaldolese Benedictines welcome guests to experience their life of contemplation and prayer. OLSON: The monks sustain their way of life through their retreat ministry and contributions from friends. They combine solitude and community, living as hermits in individual cells and gathering for prayer throughout the day.

OLSON: The monks sustain their way of life through their retreat ministry and contributions from friends. They combine solitude and community, living as hermits in individual cells and gathering for prayer throughout the day. FR COLUMBA STEWART (

FR COLUMBA STEWART ( HUSTON: I used to see what I was doing as my path to the Pulitzer Prize, and that is long gone. Now it’s my way of serving. That’s how it see it.

HUSTON: I used to see what I was doing as my path to the Pulitzer Prize, and that is long gone. Now it’s my way of serving. That’s how it see it. FR COLUMBA: The real dynamic of the Rule is to move from the self to the other. What Benedict is doing is providing a charter for making a community that really endures and that can encompass a variety of people. They’re all there for some purpose that’s really beyond themselves, this spiritual quest, and they recognize they can’t do it by themselves.

FR COLUMBA: The real dynamic of the Rule is to move from the self to the other. What Benedict is doing is providing a charter for making a community that really endures and that can encompass a variety of people. They’re all there for some purpose that’s really beyond themselves, this spiritual quest, and they recognize they can’t do it by themselves. disciplined, and that’s what people are recovering, and then they’re figuring out ways that they can live that as individuals, as families, as loose associations of friends who find this particular path to be helpful, sustaining, and nourishing to them.

disciplined, and that’s what people are recovering, and then they’re figuring out ways that they can live that as individuals, as families, as loose associations of friends who find this particular path to be helpful, sustaining, and nourishing to them.