FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: It feels somehow appropriate that the very last story I filed for this program was from Kolkata, last  week, about the legacy of Mother Teresa. It was from this city—and on the same subject—that I did my very first story for Religion & Ethics newsweekly. In nearly two decades, in hundreds of reports, grey—like my own scalp--became a dominant color. Few issues can be seen in absolutely black and white terms. They are fraught with complexity and often unforeseen consequences. Take surrogate motherhood— a billion dollar industry in India in which poor women were hired to carry the fetuses of foreign biological parents.

week, about the legacy of Mother Teresa. It was from this city—and on the same subject—that I did my very first story for Religion & Ethics newsweekly. In nearly two decades, in hundreds of reports, grey—like my own scalp--became a dominant color. Few issues can be seen in absolutely black and white terms. They are fraught with complexity and often unforeseen consequences. Take surrogate motherhood— a billion dollar industry in India in which poor women were hired to carry the fetuses of foreign biological parents.

KIRSHNER ROSS-VADEN: Coming here to India, these women, they don’t want my child. It’s very cut and dry. They do not want my child. They want my money, and that is just fine with me.

DE SAM LAZARO: It’s not fine with everyone.

DR. ARTHUR CAPLAN (Professor of Bioethics, University of Pennsylvania): The contracts usually are written, to be blunt, to protect the wealthy people who are commissioning the baby.

DE SAM LAZARO: In 2016, India banned transnational surrogacy.

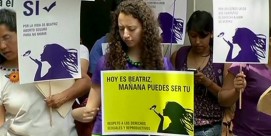

Then there’s the wrenching issue of abortion, which is now banned in the predominantly Catholic nation of El Salvador. Since 1997, abortion has been illegal in El Salvador with no exceptions, which had once existed for cases such as rape, incest, or threat to the mother’s life. Dozens of women have been prosecuted for illegal abortions, in some cases for aggravated homicide.

Then there’s the wrenching issue of abortion, which is now banned in the predominantly Catholic nation of El Salvador. Since 1997, abortion has been illegal in El Salvador with no exceptions, which had once existed for cases such as rape, incest, or threat to the mother’s life. Dozens of women have been prosecuted for illegal abortions, in some cases for aggravated homicide.

In India on the other hand, abortion on demand is legal. But it is used widely to terminate female pregnancies in a land where boys are preferred. Sex selection is illegal but the law is hard to enforce, as we found in this candid exchange with a Mumbai obstetrician:

DR. KAKODKAR: I am not in favor of it.

DE SAM LAZARO: But do you do it occasionally when requested to?

DR. KAKODKAR: Yeah, yeah, I do. I cannot deny that.

DE SAM LAZARO: Terminations are the chief source of your income?

DR. KAKODKAR: Very much so.

DE SAM LAZARO: Much more than delivering babies?

DR. KAKODKAR: Very much, very much.

DR. KAKODKAR: Very much, very much.

DE SAM LAZARO: The sobering content notwithstanding, candid interview are a kind of journalistic holy grail, since they help powerfully deliver a story. Many of my stories have concerned human suffering and one of the most effective ways to tell these is through the work of social innovators and entrepreneurs, many driven by deep faith. Like Sister Cyril Mooney, that other nun from Calcutta whose pioneering work in educating poor has won worldwide acclaim.

SISTER CYRIL MOONEY: Our approach is to educate the child, put the child standing on their feet, give them a good job, and then they’re settled for life.

DE SAM LAZARO: Dr. Catherine Hamlin, treating women with fistulas in Ethiopia. Sunitha Krishnan, providing refuge and training for trafficked young women in India. Entrepreneur Chid Liberty, starting a garment industry in his native Liberia despite ebola.

Like this one, most poverty alleviation ideas place an emphasis on improving the lives of women. The payoff higher, experts say, because women focus their energy on their families and communities. Men focus on themselves.

Like this one, most poverty alleviation ideas place an emphasis on improving the lives of women. The payoff higher, experts say, because women focus their energy on their families and communities. Men focus on themselves.

At the Barefoot College, which trains rural women to become solar technicians, Bunker Roy put it this way:

BUNKER ROY (Founder, Barefoot College): We’ve come to the sad conclusion men are untrainable. They're restless.

DE SAM LAZARO: Humor is always a powerful storytelling tool.

And finally thank Bob Abernethy and the team at Religion and Ethics Newsweekly. It’s been a million mile journey, literally making the foreign less foreign. I could not have dreamed it would take me to Kalamazoo and Timbuktu. You saw it here.

For Religion and Ethics Newsweekly, this is Fred De Sam Lazaro.

week, about the legacy of Mother Teresa. It was from this city—and on the same subject—that I did my very first story for Religion & Ethics newsweekly. In nearly two decades, in hundreds of reports, grey—like my own scalp--became a dominant color. Few issues can be seen in absolutely black and white terms. They are fraught with complexity and often unforeseen consequences. Take

week, about the legacy of Mother Teresa. It was from this city—and on the same subject—that I did my very first story for Religion & Ethics newsweekly. In nearly two decades, in hundreds of reports, grey—like my own scalp--became a dominant color. Few issues can be seen in absolutely black and white terms. They are fraught with complexity and often unforeseen consequences. Take  Then there’s the wrenching issue of abortion, which is now banned in the predominantly Catholic nation of

Then there’s the wrenching issue of abortion, which is now banned in the predominantly Catholic nation of  DR. KAKODKAR: Very much, very much.

DR. KAKODKAR: Very much, very much. Like this one, most poverty alleviation ideas place an emphasis on improving the lives of women. The payoff higher, experts say, because women focus their energy on their families and communities. Men focus on themselves.

Like this one, most poverty alleviation ideas place an emphasis on improving the lives of women. The payoff higher, experts say, because women focus their energy on their families and communities. Men focus on themselves.