In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Fantasy Coffins in Ghana

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Saturdays are set aside for funerals in Accra. In the numerous congregations that line the streets and alleys, the air is filled at times with prayer, most times with song blaring at its electronic limits. And nowhere, it seems, is there any outward sign of sorrow or grief. With few exceptions, like the death of a young person, my host here said that’s the way it is.

NII ADEI KLU: When somebody dies in Christ, or dies a Christian, it’s a good thing because, I mean, he’s going to God, he has died on a good path. But when somebody dies a pagan or somebody who does not know God, then people cry because his soul is lost.

DE SAM LAZARO: We saw little evidence of any crying on this Saturday. And it would be hard to discern a lost soul. The vast majority of people in this city strongly profess some form of Christianity. About 16% of Ghanaians are Muslim. Most live in the country’s north.

Funerals are major social events that bring together far-flung extended families. Obituary flyers and posters cover neighborhood walls. Often they are anticipated years in advance, and say much about a person’s status. Nowhere is that more evident than in the coffins favored by the Ga ethnic group in southeastern Ghana.

Funerals are major social events that bring together far-flung extended families. Obituary flyers and posters cover neighborhood walls. Often they are anticipated years in advance, and say much about a person’s status. Nowhere is that more evident than in the coffins favored by the Ga ethnic group in southeastern Ghana.

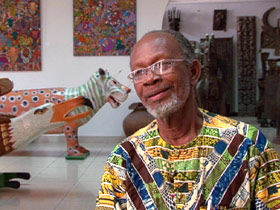

ABLADE (Art Dealer): People who have achieved in their lifetime.

DE SAM LAZARO: The well to do.

ABLADE: Well to do. And usually it has to show your area of achievement. If one were a fisherman, they would show some canoe or fish or things like that. If you are a driver and own transport, they would show some transportation.

DE SAM LAZARO: We saw coffins waiting for the next crab fisherman, hunter — or could this one be for an animal lover? There’s one for the beer lover, farmer, and athlete. Fantasy coffins have gained a reputation for their high art. Many are sold to foreigners and collectors.

At the root of all this is a strong tradition — of honoring, even worshipping ancestors, says Ablade. Grand funerals are a way for the living to please the newly departed elder, to continue the communion with those who went before and to ask for blessings.

At the root of all this is a strong tradition — of honoring, even worshipping ancestors, says Ablade. Grand funerals are a way for the living to please the newly departed elder, to continue the communion with those who went before and to ask for blessings.

ABLADE: The belief is simply that the ancestors are there and if you’re going to meet them, you must meet them properly. I mean, his being there becomes a blessing to the family. They will start calling upon him, “Hey, send us something, this week, things are not so good…”

DE SAM LAZARO: In fact, funerals, even without the expensive fantasy coffins, are a huge financial drain on families: Providing meals and libation for dozens, sometimes hundreds of guests, the musicians, and of course the morticians.

KLU: The family will be paying this money with interest, maybe the person has left children behind, or he has left some properties, sometimes it has to be auctioned or sold to defray the debts which has been incurred.

DE SAM LAZARO: There are calls from time to time from religious leaders to cut out the excess. But funerals are an investment in harmony with one’s ancestors, a true measure of one’s esteem for the departed. How, many families ask, do you put a limit on that?

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Accra, Ghana.