In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Elaine Pagels

BOB ABERNETHY: Now, a profile — and some religion history. It concerns the early Christian movement, and documents discovered nearly 60 years ago that reveal an early Christianity many find surprisingly diverse. This is also the personal story of Elaine Pagels, historian of religion at Princeton University. She has written best-selling books on what are called “The Gnostic Gospels.” Mary Alice Williams reports.

MARY ALICE WILLIAMS: Elaine Pagels seems comfortable keeping Christianity at an academic distance. But in 1982, it got personal. Her only child had just been diagnosed with a terminal lung disease. Pagels found herself outside the Church of the Heavenly Rest, an Episcopal church in Manhattan, doubting its orthodoxy, needing its sustenance.

ELAINE PAGELS (Author, THE GNOSTIC GOSPELS): I was extremely upset. I hadn’t slept in days. Distraught. I was trying to calm myself by running that morning. It seemed to me the possibility of a church like this, the way it engages the issues of life and death, put the prospect of losing a child into a context that was much larger than an ordinary one.

WILLIAMS: Raised by nonobservant Protestant parents, Pagels shocked them by joining an Evangelical church at the age of 13, then quit when the church announced a friend of hers would go to hell because he’d not been “born again.”

Ms. PAGELS: I realized that I did not accept what they were saying. I didn’t agree with it. It didn’t make sense to me.

WILLIAMS: But the passionate faith of the Evangelicals had affected her.

Ms. PAGELS: I was aware that something very powerful had engaged me. What is so powerful about it? How does it transform people in the way that it does? I remembered that very well. So I decided that I would have to seek for myself.

WILLIAMS: No small search. She learned Greek and the ancient language Coptic to study the origins of Christianity, and in 1972 became part of a translation team with early access to a gold mine. In 1945, an Egyptian peasant searching for fertilizer found an earthenware jar filled with manuscripts in a cave near the village of Nag Hammadi. His mother burned many of the documents for kindling. What survived were 52 sacred texts, some as old as the four Gospels.

Ms. PAGELS: I realized that conventional views of Christian faith that I’d heard when I was growing up were simply made up — and I realized that many parts of the story of the early Christian movement had been left out.

WILLIAMS: What came to be known as the Gnostic Gospels (from the Greek word meaning “to know”) is an explosive, some say heretical, look at Christianity’s evolution. And evidence of fierce theological debate before Christianity was encoded into a set of beliefs.

Ms. PAGELS: What we find when we go back there is that the earliest evidence is very diverse. That’s not the story we were told as Christians, because the Christian church chose to simplify it and give us a single version of the story.

WILLIAMS: In order to preserve Christianity, scholars believe church fathers had to unify a fractious lot of competing voices. They found many Gnostic ideas intolerable. In particular, the idea that each of us can become connected to God without priestly intervention was a threat to their authority. Scholars believe the Gnostic texts were buried at Nag Hammadi at the close of the fourth century because church fathers had ordered the monks to burn them.

WILLIAMS: In order to preserve Christianity, scholars believe church fathers had to unify a fractious lot of competing voices. They found many Gnostic ideas intolerable. In particular, the idea that each of us can become connected to God without priestly intervention was a threat to their authority. Scholars believe the Gnostic texts were buried at Nag Hammadi at the close of the fourth century because church fathers had ordered the monks to burn them.

Ms. PAGELS: The bishop who wanted authority consolidated in himself told them, “Get rid of all those books. You don’t need all those books. All you need are the ones that I will mention now.” And then he mentions a list, which is our first list of the 27 books of the New Testament. So he told them.

WILLIAMS: And that was politically necessary at the time?

Ms. PAGELS: At the time, I think it was absolutely essential for the survival of the movement, because it was so much threatened by persecution and by complete scattering. So it was at that time necessary, probably, to consolidate the church and try to make a simple message accessible and universal.

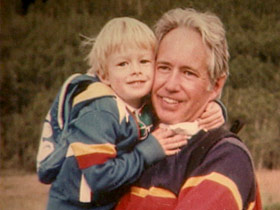

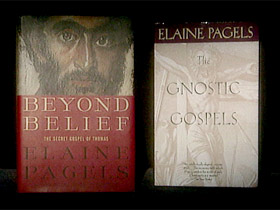

WILLIAMS: Pagels’s research resulted in her surprise best-seller,THE GNOSTIC GOSPELS. In the wake of that triumph she found her soulmate, married, and became a mother. Then the bottom dropped out. In 1987, their child Mark, at the age of six and a half, died. A year after that, her husband Heinz died in a climbing accident.

Ms. PAGELS: One can think, “Well, I’ve been doing it pretty well, and things should turn out well.” And when you do that and things turn out horrendously, our impulse, because of our tradition, is to blame ourselves. After all, if you read the book of Genesis, it says people who do good things receive good things, and people who do bad things, you know, have terrible things happen. It certainly would have shattered any kind of conventional faith.

Ms. PAGELS: One can think, “Well, I’ve been doing it pretty well, and things should turn out well.” And when you do that and things turn out horrendously, our impulse, because of our tradition, is to blame ourselves. After all, if you read the book of Genesis, it says people who do good things receive good things, and people who do bad things, you know, have terrible things happen. It certainly would have shattered any kind of conventional faith.

WILLIAMS: Elaine Pagels’s intellect may have lacked conventional faith, but she had the heart of a spiritual seeker. And her path was the church.

Ms. PAGELS: One somehow has to go on and find a way to hope again. And I found in that church, the people gathered there in various ways, some solace and some help.

WILLIAMS: Pagels transformed pain into scholarship, digging again into the trove from Nag Hammadi. And this year hit the best-seller list with BEYOND BELIEF: THE SECRET GOSPEL OF THOMAS. Scholars believe the Apostle Thomas’s Gospel, along with Mathew’s, Mark’s, and Luke’s.

Ms. PAGELS: I was expecting it to be abominable, blasphemous heresy. That’s what I was told. What I now see is that it’s not necessarily contrary; it’s complementary. And it can open up new vistas on that tradition. In fact, I find it very moving and spiritually resonant.

WILLIAMS: Pagels believes John was written to counter Thomas.

Ms. PAGELS: The Gospel of John speaks of Jesus as the “light of the world,” the “Divine One” who comes into the world to rescue the human race from sin and darkness, and says, “if you believe in him, you can be saved. You can have everlasting life. If you don’t believe in him, you go to everlasting death.” The Gospel of Thomas, on the other hand, speaks of Jesus as the “Divine Light” that comes from heaven, but says, “and you, too, have access to that divine source within yourself” — even apart from Jesus. That might suggest you don’t need a church, or a priest, or an institution.

Ms. PAGELS: The Gospel of John speaks of Jesus as the “light of the world,” the “Divine One” who comes into the world to rescue the human race from sin and darkness, and says, “if you believe in him, you can be saved. You can have everlasting life. If you don’t believe in him, you go to everlasting death.” The Gospel of Thomas, on the other hand, speaks of Jesus as the “Divine Light” that comes from heaven, but says, “and you, too, have access to that divine source within yourself” — even apart from Jesus. That might suggest you don’t need a church, or a priest, or an institution.

WILLIAMS: Do you think that belief in Jesus as God has been overemphasized in Christianity?

Ms. PAGELS: I think it has. Most people think that if you’re talking — if you and I are talking about religion, we’re talking about, “Do you believe in God?” “Do you believe in Jesus as the son of God?” It’s not all about what you believe. It’s about what values we share. It’s about what commitments we have to the sacredness of life, for example.

WILLIAMS: Some say that you smack of New Age religiosity.

Ms. PAGELS: People have said that this sounds like a New Age kind of teaching, and that I find kind of humorous. I mean, if 2,000 years is “new,” then I suppose it is.

WILLIAMS: Pagels’s work in bringing these ancient texts to life and spreading them beyond academia has challenged the historical view of the western world’s dominant religion. And rocked the Christian world.

Ms. PAGELS: There are people who think that this kind of exploration is faithless, is antithetical, is damaging to God’s truth. Of course, I’m not one of those people.

WILLIAMS: Following the deaths of her husband and son, Elaine Pagels never imagined participating in life again. Now, 15 years later, she is remarried and joyful. And perhaps more spiritual than she’d ever known she could be.

Ms. PAGELS: I realize that I cannot live without a spiritual dimension in my life. I mean, I was brought up to believe that that was some archaic relic that we could live without. I don’t think that is true anymore. The sense of a spiritual dimension in life is absolutely important and the religious communities are also important. The question of believing in a set of creedal statements is a lot less important, because I realize the Christian movement thrived then and can now on other elements of the tradition.

WILLIAMS: For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Mary Alice Williams.