In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Miroslav Volf

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: The common reaction of most of us to pictures of Americans killed and defiled in a foreign land is a call for revenge. But we have a profile today of a Christian theologian who not only condemns violence but also insists that even with the mob in Fallujah — even with a Hitler or a Saddam Hussein — there is no exception to Christ’s command to love and forgive our enemies. He is Miroslav Volf, a former Croatian who emigrated to the U.S. 15 years ago.

Volf teaches at the Yale Divinity School, where his specialty is how faith can connect to everyday life — especially to questions about violence.

The fighting in the early ’90s between Serbia and Croatia challenged Volf’s commitment to nonviolence. He was the son of a pacifist Pentecostal minister. How should he react? He spoke of that recently with Krista Tippett of Minnesota Public Radio.

MIROSLAV VOLF (Director, Center for Faith and Culture, Yale Divinity School): Once this occupation of my own country had taken place, I suddenly felt a surge of violence within me, and I was not sure exactly what I ought to do as a Christian. And that put on the map for me the question, how does one think as a Christian about situations of violence, and how does Christian faith interact in our violent world?

MIROSLAV VOLF (Director, Center for Faith and Culture, Yale Divinity School): Once this occupation of my own country had taken place, I suddenly felt a surge of violence within me, and I was not sure exactly what I ought to do as a Christian. And that put on the map for me the question, how does one think as a Christian about situations of violence, and how does Christian faith interact in our violent world?

ABERNETHY: Volf knows religion is often used to justify violence, but he also insists it can bring about reconciliation.

Dr. VOLF: At the very heart of the Christian tradition is this impulse that [the] enemy is there as a human being who needs to be embraced, who needs to be taken into the fold, who needs to be made from [an] enemy into a friend.

ABERNETHY: Does an enemy have to repent and ask for forgiveness before you can forgive that enemy?

Dr. VOLF: Before I can make that enemy my friend, yes. But before I can start the process of making an enemy a friend, no.

ABERNETHY: Volf acknowledges how difficult reconciliation is — even harder for nations than for individuals. Nevertheless, he thinks reconciliation can happen in the former Yugoslavia, and he hopes it can happen between Americans and Islamic terrorists.

Dr. VOLF: I think the process of negotiation — process of seeing ourselves through their eyes, helping them to see themselves in our eyes — these kinds of processes are very important. I think that is what the stuff of politics is made [of].

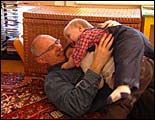

ABERNETHY: Volf and his wife, also a Yale professor, have two young sons, Nathaniel and Aaron, six and two. I asked Volf what he teaches his boys about fighting.

Dr. VOLF: We all try to teach our children, well, share that toy, right? There’s your turn, and there’s other person’s turn. “Well, look what Aaron wants now. Try to imagine yourself in his shoes. What would you do if you were in his place?”

Dr. VOLF: We all try to teach our children, well, share that toy, right? There’s your turn, and there’s other person’s turn. “Well, look what Aaron wants now. Try to imagine yourself in his shoes. What would you do if you were in his place?”

ABERNETHY: Does it work?

Dr. VOLF: Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t work. But my sense is that is what education — that is what moral education is all about.

ABERNETHY: Do you spank them?

Dr. VOLF: I don’t.

ABERNETHY: Volf has become an Episcopalian, and he teaches an adult education class. He recalled how his older brother, when he was just six years old, was killed, apparently by the carelessness of a Croatian soldier who was playing with him. Volf told the story to his class.

Dr. VOLF: I remember very vividly early on how my parents have told me how they never pressed any legal action against the person, the soldier. They never wanted to receive any recompense, which that young soldier had offered to do for them. They just forgave him. Everything in you cries for justice, for revenge, and yet somehow, in the deep resources of your soul, a soul that was shaped by what God has done for us, you have strength to forgive.

ABERNETHY: As Volf studies religion and everyday life as director of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture, he emphasizes his belief that for Christians, pursuing justice is not enough. They must go further.

ABERNETHY: As Volf studies religion and everyday life as director of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture, he emphasizes his belief that for Christians, pursuing justice is not enough. They must go further.

Dr. VOLF: If I say “I forgive you,” I have implicitly said you have done something wrong to me. But what forgiveness is at its heart is both saying that justice has been violated and not letting that violation count against the offender. I release the offender who is [an] offender from what the justice would demand to be done.

ABERNETHY: Volf says in a world of 1.3 billion Muslims and 2 billion Christians, dialogue between the two faiths is of urgent importance. This week he joined other Christian and Muslim scholars as they sought greater mutual understanding by studying their respective scriptures together. I asked Volf about differences among religions.

Dr. VOLF: [The] Christian God is different, is different than the Muslim God, but it’s not other than the Muslim God. I do believe that Muslims and Christians and Jews pray to the same God. And yet they understand who God is in significantly different ways.

ABERNETHY: Volf insists that differences between religions should not prevent mutual respect.

Dr. VOLF: I find it almost like an insult to human nature, an insult to religious people, whatever religion they belong to, to say, “We have to agree at the bottom in order to be able to live in peace.” I want to believe that if you and I disagree about something, that we can still be very good neighbors; indeed, that we can be friends. And that ought to apply also for our various world religions. We can disagree. We can disagree on profound matters of life and nevertheless, we can live in peace with one another. Why? Because I do believe that different religions have their own internal resources which will motivate us to live in peace, indeed, to love those who differ from us.

Dr. VOLF: I find it almost like an insult to human nature, an insult to religious people, whatever religion they belong to, to say, “We have to agree at the bottom in order to be able to live in peace.” I want to believe that if you and I disagree about something, that we can still be very good neighbors; indeed, that we can be friends. And that ought to apply also for our various world religions. We can disagree. We can disagree on profound matters of life and nevertheless, we can live in peace with one another. Why? Because I do believe that different religions have their own internal resources which will motivate us to live in peace, indeed, to love those who differ from us.

ABERNETHY: Volf acknowledges that public safety requires that dangerous people be confined. But he insists the first response to violence should be to make peace, not to strike back.

The conference in Washington at which Volf spoke was led by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, the leader of the world’s Anglicans. The topic: how Christians and Muslims can learn from and live with their religious differences.