Celtic Spirituality

Editor’s Note: John O’Donohue died in 2008.

BOB ABERNETHY: And now, the rediscovery of Celtic spirituality. When the pagan Celts of Ireland were converted to Christianity by St. Patrick in the fifth century, they brought with them their love of nature and friendship and their awareness of the sacred in all the most ordinary parts of life. Today, Celtic spirituality is resonating with more and more Americans, as Judy Valente reports from Chicago.

JUDY VALENTE: They are the quintessential images of Irish-American Catholicism, the bagpipers, the wearing of the green, the homage to St. Patrick who would convert the Celts of Ireland to Christianity in the fifth century. But this year, a few blocks off the parade route in Chicago, something different was happening. Bagpipes, yes, because this is Old St. Patrick’s Church founded by Irish immigrants in the nineteenth century, its walls and ceiling adorned with art depicting the Irish Book of Kells, the ninth-century illustrated gospel. While the saint was being toasted elsewhere, people here were beginning the study of something different: Celtic spirituality.

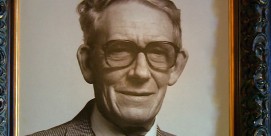

MR. JOHN O’DONOHUE (Theologian): I think the exciting thing in relation to Celtic spirituality is that a lot of American people are either of proximate or ultimate Celtic origin, and I think with the arrival of this, that they find in this something that is their own, and they inhabit it and can dwell in it from within.

MR. JOHN O’DONOHUE (Theologian): I think the exciting thing in relation to Celtic spirituality is that a lot of American people are either of proximate or ultimate Celtic origin, and I think with the arrival of this, that they find in this something that is their own, and they inhabit it and can dwell in it from within.

VALENTE: A nomadic tribe that first appeared in Eastern Europe hundreds of years before Christ, the Celts migrated westward, finally settling in the green fields of Ireland. The Celts were fierce warriors, but when they weren’t at war they lived simple, agrarian lives. They found meaning in the most routine tasks of life, sacredness in the nature around them, and spiritual sustenance in the close ties of friendship.

But they also valued solitude and silence. This is the hushed, beautiful, and brooding landscape that was the Celtic environment.

MR. O’DONOHUE: I do believe the landscape has a huge influence on shaping the rhythm of mind and the shape of perception. The diversity of the Irish landscape, the amazing kind of light that’s in it. There is something in the Irish landscape that naturally anchors a spirituality which somehow reveals or discloses the eternal. The Celtic spirituality had a wonderful recognition of nature as the theater of divine presence. That nature, in other words, wasn’t an object, it wasn’t matter; it was the place where the divine presence articulated its imagination and showed, in some sense, its rhythms and its beauty.

Unidentified Man: (Gaelic spoken)

VALENTE: The Gaelic tongue, language of the Celts, can still be heard in the rustic west of Ireland where John O’Donohue lives in a small cottage a mile from the nearest person.

VALENTE: The Gaelic tongue, language of the Celts, can still be heard in the rustic west of Ireland where John O’Donohue lives in a small cottage a mile from the nearest person.

MR. O’DONOHUE: (Gaelic spoken)

VALENTE: A scholar and poet, he visits this country to articulate the Celtic sense of wonder at the simple fact of creation.

MR. O’DONOHUE: I’d say the thing that I’ve never got over is the strange fact of being here on the planet at all. It’s quite unbelievable to be on the Earth.

VALENTE: To the Celts, the circle symbolized the interconnectedness of everything: suffering and redemption, death, and resurrection. There were no hierarchies. Life was an unending circle with no beginning and no end.

MR. O’DONOHUE: So it never separated mind from body, soul from body, or God from us, or masculine from feminine, or nature from the divine, or time from eternity, but it had them all together within the one kind of circle.

VALENTE: In his writing, O’Donohue describes the Celtic view of close friendship as a way to find our own secret signature, our individuality, and our creativity. Another person can be the mirror into our own souls. The community provides us with “the gentle nest of belonging.” But O’Donohue laments what he calls the “screaming loneliness” of modern life, the fragmentation of community.

MR. O’DONOHUE: We get so trapped in the world, we get trapped in our name, our role, our relationships, our work, and we become so predictable. And meanwhile, behind the controlled facade of our external life, there is a huge restlessness, a huge hunger to be seen for who we really are, to be known.

MR. O’DONOHUE: We get so trapped in the world, we get trapped in our name, our role, our relationships, our work, and we become so predictable. And meanwhile, behind the controlled facade of our external life, there is a huge restlessness, a huge hunger to be seen for who we really are, to be known.

VALENTE: But how to bridge the gap between the contemplative landscape the Celts inhabited and the world of the modern urbanite? Colleen Grace is a lawyer, married with two small children. A parishioner at Old St. Patrick’s Church, she lives in the heart of Chicago.

MS. COLLEEN GRACE: I think what it’s all about is bringing God into the everyday ordinariness of life and really, you know, appreciating the special moments that you have here. In the Celtic way of life, there were prayers for everything. There were prayers for waking up in the morning; there were prayers for preparing breakfast; prayers for preparing the fire; prayers for putting the fire out at night, and, you know, redoing it the next morning. So just the idea that there could actually be prayerful moments in every small detail of what you do made me, I think, look at things a little bit differently. It’s a very joyous way of looking at the world, and I don’t think you have to be Catholic or Irish at all to appreciate the joy of living.

VALENTE: St. Patrick found the Celts receptive to Christianity, which shared their view of the sacredness of nature and of friendship. O’Donohue came to Chicago to help establish a center for the study of Celtic spirituality amid the beauty of St. Patrick’s Church.

MR. O’DONOHUE: The best any new spirituality can offer anybody is either an awakening, a deepening, or a challenging or a healing of the way they see already. I believe that consciousness is the only bridge to reality, and I think that there is, in Celtic spirituality, a rhythm of seeing which can alter the way that one approaches the world.

VALENTE: Blessings were a part of the Celtic tradition. They’re also in the poetry of John O’Donohue, expressing the Celtic sense of awe at the world outside us and within us.

MR. O’DONOHUE: “May the sense of something absent enlarge our lives and may our souls be as free as the ever-new waves of the sea. May we succumb to the danger of growth. May we live in the neighborhood of wonder. And may we belong to love with the wildness of dance, and may we know that we are ever embraced in the kind circle of God.”

VALENTE: This is Judy Valente reporting.