DEBORAH POTTER, guest anchor: The old saying "time heals all wounds" doesn't always apply, especially when it comes to grief. Grieving is a normal human reaction to loss. It's painful, and it's hard work. For some people, the best way to do the hard work of grieving is in the company of others. Bob Faw found a place in Maine where that work has been going on for more than a dozen years.

BOB FAW: This is a camp like no other, filled with laughter and beauty -- and pain. A camp named Ray of Hope for people grieving the death of a spouse, a child, or a friend, where they learn how to accept that death and go on.

Michelle Ouellette, for example. Several months ago cancer claimed her favorite aunt Theresa Frost, who virtually raised Michelle.

MICHELLE OUELLETTE: She was my mentor and my best buddy. She was a one-in-a- million lady, and I'll never have another one like her ever. I miss her dearly. I always will.

FAW: Tammi Hooper knows what that's like. Four months ago her singer-song-writing husband James died suddenly at the age of 31.

TAMMI HOOPER: It is always there, every waking moment, and for me this is just getting to know other people who feel like I feel.

FAW: Tammi and Michelle and 35 families, many whose loved ones died unexpectedly, were hurting when they came here, where they were embraced by others who had been hurting. Dale Marie Clark lost both her husband and her son in the space of just 10 weeks.

DALE MARIE CLARK (Founder, Camp Ray of Hope): I was shaken to the very core and not sure if I could survive that.

FAW: What Dale Clark learned, what helped her survive, is what she has been imparting to others since she founded the camp in 1995 as part of the Hospice Volunteers of Waterville, Maine.

Ms. CLARK: You can give them hope. You can say I felt the same way, you know. I felt the same way, and it does get better, you know, you do get better. You do get through it.

FAW: To help them get through it the camp holds support groups and workshops. In this one, Tammi Hooper fit photographs inside a so-called memory pillow.

Ms. HOOPER: At least I'll have this to hold on to remember, you know. But it just gives me something physical to touch.

FAW: Ten-year-old Julie McConnell thought her mother, who died this year in a motorcycle accident, would have liked the fabric which Julie chose for her memory pillow

JULIE MCCONNELL: I think it will help a little bit. Just having her picture inside here, I think that will help.

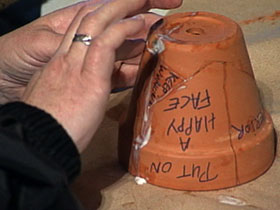

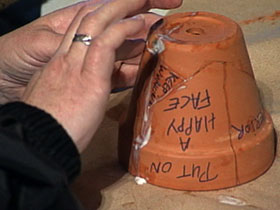

FAW: Sometimes the exercises are painful. In this one, those who are grieving break a clay pot, a pot shattered just as their lives have been.

Ms. OUELLETTE: It tends to signify that feeling of just how it feels, like somebody is just smashing your whole life apart. All of a sudden your life is just smashed, and you don't know if you'll ever be able to put it back together again.

FAW: Carefully, lovingly, from the broken shards they reassemble the pot, just as they are trying to do with their own lives.

Ms. OUELLETTE: You're trying to put your life back together again in as best a fashion as you can, and you know it will never be the same.

Ms. CLARK: It's work. It's hard work. Grief is hard work. It really is. It is exhausting and, you know, it takes, really, to be able, to be willing and able to share whatever those feelings are or whatever those words are that you need to share. If you work through those intense, intense feelings in the beginning, then you're letting go of a little piece of that intense pain.

FAW: At this Methodist church camp they are taught to mend what death has broken, and what they learn is that there is no right or wrong way to grieve -- that young or old, male or female, there is no time-table for dealing with death, that everyone handles death differently.

TERRI WARREN: The books tell you time, time, the whole thing, that everything takes time. They just don't say how much.

FAW: This camp has also helped Terri Warren, who lost her 17-year-old daughter Savannah six years ago in a car accident, by putting her thoughts into words -- what Camp Ray of Hope calls journaling. It has helped her daughter Becca.

BECCA WARREN: It's like me speaking to someone. It's all the stuff that I can't say I can actually say to the notebooks.

FAW: And it's part of healing?

BECCA: Exactly. That's what I find it to be. So just kind of like a safe harbor.

FAW: It is different for young children, who often do not understand what "forever" means and think their parent or sibling is going to come back. Children process death differently than adults.

DEB CROCKER (Youth Services Coordinator): They're not like adults who can just sit in a circle and talk about their loss. So you need to give them things to do, and in that midst of talking, of doing an activity, they'll talk. They'll talk about their grief. They'll talk about their loss, the person that they lost.

FAW: So as they play they grieve?

Ms. CROCKER: They do.

FAW: So here, whether it's Paige Lilly working on an ornament to celebrate her mother Tara, who died from cancer, or during the chaos of an egg toss, children don't just release pent-up frustrations. They also acknowledge the loss they are feeling.

UNIDENTIFIED GIRL: If the person who died was here right now, I would like to get on his lap and have him read me a book.

FAW: And in this clown workshop, where Tammi Hooper brings her daughter, Emily, children learn that in laughter, too, there is healing.

MARLENE MYERS (Merry Giggles the Clown): I just believe there is an inside part of you that needs to laugh, and it overcomes sorrow many times.

FAW: So when you're sad it's OK to laugh? You want them to laugh?

Ms. MYERS: Yes. Exactly, yes

FAW: What all these activities have in common, whether in the quiet moments or in being pampered, is the belief in empathy.

Ms. CLARK: Most of the time the best thing, the most powerful thing and therapeutic thing that you can do for someone who is in emotional pain is just to listen and witness and validate and not judge, and through that they're empowered.

FAW: A role for empathy and for faith, tested for Dale when tragedy struck and ultimately affirmed.

Ms. CLARK: I always believed that there was a God. But I never really felt the depth of what that faith was until I experienced the death of my husband and son. And there were times when you didn't want to live. You didn't want to go on, you know. I would sometimes pray to go to bed at night and not wake up in the morning because those deaths were so painful for me. But what I did learn through that time, and thank God for it, is that God is always there no matter.

(speaking at worship service): Divine spirit, on this day I ask for new life.

FAW: A belief which helps explain why this weekend includes a service in the chapel in the pines, where prayers are offered as the name of each dead loved one is spoken.

CONGREGATION (praying): For this, dear God, we pray.

FAW: Later, in a private ceremony, each family releases one monarch butterfly, a symbol that dealing with death is a journey and that they, too, can be set free.

FAW: Does the journey ever really end?

SCOTT WARREN: I don't believe it does. This was a tragic event in our life that has changed us all as people. We've had to relearn who we are and where we fit in the world today.

FAW: But at least at Camp Ray of Hope they, too, just like those clay pots, can be put back together again.

TERRI WARREN: You know, there is part of me that will always be missing. But the lows that I have are shorter now than they used to be. The highs are longer. I find enjoyment in things.

FAW: So the pain is still there? You learn to live with it?

TERRI WARREN: You do. You find, I think, a place for it.

FAW: You go on?

TERRI WARREN: You go on. You do what you have to do.

FAW: Learning to do so at a camp where the shattered pieces of their lives can be restored and where they emerge stronger in places that were broken.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, this is Bob Faw in Winthrop, Maine.