In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

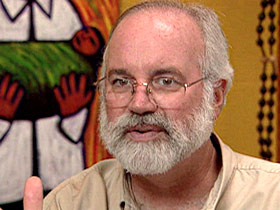

Gang Priest

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Today, we have a special look at the gang world of Los Angeles, a place where violent death is common and hope, scarce — but not totally absent, thanks to a dedicated, savvy priest. Lucky Severson begins his report on the street with a gang member.

LUCKY SEVERSON: He goes by the name of Angel and he is in the process of trying to undo what he has done a good part of his life. Like most gang members or “gang bangers,” in addition to his life of street crime, Angel was a graffiti artist. We look at the scribble and see scribble. Angel sees something else.

(To Angel): Angel, what is the point of this?

ANGEL: For fame. See who can write the most. The more you see that name, the more respect and fame you get among them and their peers.

SEVERSON: So when a gang member does this and it is cool, it elevates his prestige?

ANGEL: His prestige. It shows how good he is. You know, he has style. All of these matter amongst them.

SEVERSON: Angel was one of them, until prison and now this effort at redemption. His real family was messed up and drugged out. His gang family took care of him, and he took care of them. Angel was no angel.

SEVERSON: Angel was one of them, until prison and now this effort at redemption. His real family was messed up and drugged out. His gang family took care of him, and he took care of them. Angel was no angel.

ANGEL: Wherever you have your friends, you stick together as tight as you can.

SEVERSON: But you take other kids’ lives?

ANGEL: Well, you have to before they take yours. What are you going to do? If someone is coming to your block and is going to shoot you, what are you going to do, let them shoot you down? Let them shoot your friends? It can’t go down that way. So, it’s sad that you have to die just for a stupid street.

SEVERSON: Robert is another homeboy — local slang for kids in a gang. Except for the eight years in prison for car-jackings and robbery, the gang was the only family he knew.

ROBERT: I joined a gang for a family. I never had one when I was growing up. I joined the gang for a family. That’s it.

SEVERSON: Now they have a new gang, which is also their employer: Homeboy Industries. They call their boss “G-dog” or “Father G” — also known as Father Greg Boyle, Jesuit priest of the poorest pastorate in Los Angeles.

Father GREG BOYLE: I buried my first kid in 1988. I buried my 128th yesterday. There is a lethal absence of hope in a community like this. You get more kids planning their funerals than their futures. And what you hope to do, especially in a program like this, is to help them conjure up an image of what tomorrow will look like, because if you can’t see your future, you aren’t going to find your present very compelling. And that is a dangerous place to be.

Father GREG BOYLE: I buried my first kid in 1988. I buried my 128th yesterday. There is a lethal absence of hope in a community like this. You get more kids planning their funerals than their futures. And what you hope to do, especially in a program like this, is to help them conjure up an image of what tomorrow will look like, because if you can’t see your future, you aren’t going to find your present very compelling. And that is a dangerous place to be.

SEVERSON: The surrounding neighborhood may not look dangerous. But of the 750 gang killings in Los Angeles over the past three years, many took place here, in broad daylight. Not a great place to grow up. And in the middle of it — Homeboy Industries, founded by Father Boyle and funded mostly by private contributions. Over the years, Homeboy has employed and found jobs for hundred of wasted gang members.

Father BOYLE: We get 1,000 folks a month. If they walk in, that’s hugely successful. It means they have taken this very important step, you know. It is like recovery, drug rehab. If you walk into a drug rehab, it doesn’t matter where you have been or how long you have been a drug addict: Welcome, this is really significant.

(To gang members): You guys taking care of business? What about school? What happened to school?

SEVERSON: And if they don’t cut it, he fires them. But those who stick around learn how to present themselves to a skeptical society, politely. And for the first time in their lives, they learn how to work. But it’s more than just work.

Father BOYLE: It is absolutely all religious. There is no kind of “Here’s the part that is spiritual, here’s the part that is God. Here is the part that speaks a spiritual message,” you know. It is far more important not to announce a message to the folks that come in here, but to become that message to the folks that come in here.

Father BOYLE: It is absolutely all religious. There is no kind of “Here’s the part that is spiritual, here’s the part that is God. Here is the part that speaks a spiritual message,” you know. It is far more important not to announce a message to the folks that come in here, but to become that message to the folks that come in here.

SEVERSON: Many come in, like Robert, regretting the body art they once thought was cool.

ROBERT: My first one was this, and it is gang related. Honestly, I do regret them. I wish I had none.

SEVERSON: It’s hard to get a job in a body that screams that you’re a gang banger. So Father Boyle brought in a doctor and bought a laser. There’s a waiting list to get tattoos removed. For Gloria, it’s a matter of erasing something she actually thought was fun.

GLORIA: Out on the street with my homeboys, they give me respect, I give them respect. It was just fun at the time.

SEVERSON: Gloria is not typical. Only one in 20 gang members is a girl. In this area, almost all are Latinos. Gloria’s home life was miserable. She was 16 when she joined a gang.

GLORIA: I could have lost my life a lot of times.

SEVERSON: In what kind of situations?

SEVERSON: In what kind of situations?

GLORIA: Number one, almost all of them shootings. You can’t even tell what kind of car I had. It was just full of bullet holes. It was funny at that time and it was down, what we did. I think back now, just to think I could have lost my life. My son could have lost his mom. Yeah.

Father BOYLE: It is about kids who don’t care. The kids who are shooting are kids who don’t want to kill. They want to die.

JOE: They shot me four times in the head with a .38 slug.

SEVERSON: Joe was shot after he retaliated for the drive-by killing of his five-year-old son.

JOE: I wasn’t into drugs. I was more into gangs. That was my drug. That was my addiction. It gave me a sense of power. It gave me control, respect, even though I had all those terms twisted. I didn’t know what the definition of “respect” was, except for fear. That’s what I thought it was.

SEVERSON: Withdrawing from gang life is similar to recovering from an addiction. It’s never-ending.

ANGEL: It never leaves. Because there’s still people that still know me. I still have enemies at this stage. It always follows you, you know. Anything in your life follows you.

SEVERSON: It followed fellow homeboy Miguel Gomez, who was shot and killed in June removing graffiti.

SEVERSON: It followed fellow homeboy Miguel Gomez, who was shot and killed in June removing graffiti.

ANGEL: It is not as fun as it used to be. We are not as at ease as we used to be. Now we are more, I mean, a little bit leery.

Father BOYLE: These are human beings who deserve a chance. Not even a second chance, you know. Who gave them their first one, you know? And that is what this place stands for.

SEVERSON: Police said the shooting was an old vendetta not related to Homeboy, and so the project moves on.

Father BOYLE: It is heartache and hilarity all in the same day, you know, and you’re fully engaged in the lives of people and it is eternally interesting and it’s heart soaring as you watch people possess who they are. It couldn’t be better.

SEVERSON: There’s been a shooting just right down the street, half a block away. A half hour after our interview with Father Boyle, it was all heartache.

UNIDENTIFIED POLICE CAPTAIN: We had a homicide today and that occurred about 12:30. And what we know at the present time is that the victim does work for Homeboys Incorporated.

SEVERSON: The victim was shot several times a hundred yards from the Homeboy office, on his way to remove graffiti. His name was Arturo Casas. He was 25. For homeboys, it was another death in the family.

ROBERT: Unfortunately, the gang-banging life only leads down two roads, you know. You basically go to jail or you get buried.

SEVERSON: Arturo was the 129th gang banger Father Boyle has buried. For the time being, Father G has suspended graffiti removal. But he hasn’t suspended hope.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Lucky Severson in south central Los Angeles.