In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

James L. Guth on George W. Bush and Religious Politics

Read excerpts from an essay by Furman University political science professor James L. Guth on George W. Bush and religious politics. It appears in the new book HIGH RISK AND BIG AMBITION: THE PRESIDENCY OF GEORGE W. BUSH, edited by Steven E. Schier (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004):

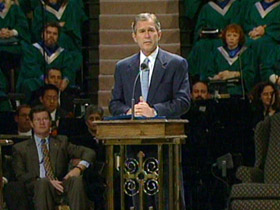

George W. Bush has testified that his call to run for the presidency came through a sermon at his second inaugural as governor. In any case, his campaign strategy, shaped by Karl Rove, focused on the GOP’s two key resources: business money and religious votes. Bush’s faith gave him unique advantages in his pursuit of the latter: he was by upbringing and affiliation a mainline Protestant; his Episcopalian, Presbyterian and Methodist roots put him squarely at the center of the old GOP religious clientele. But by experience, belief and sensibility, he was an evangelical, speaking fluently the religious language of the new party constituencies. (This perhaps explains why the 2000 National Election Study shows far more evangelicals identifying Bush incorrectly as a Baptist than correctly as a Methodist.) He often bypassed the most visible (and often unpopular) Christian right figures such as Pat Robertson, James Dobson, and Jerry Falwell, relying instead on former Christian Coalition director Ralph Reed, evangelist James Robison, and several Southern Baptist leaders. These enthusiasts assured evangelical clergy that Bush was one of them, aided by the candidate’s famous declaration that Jesus was his “favorite political philosopher.” Although Bush faced other Republicans close to religious conservatives, such as Christian right leader Gary Bauer and anti-abortion activist Alan Keyes, this appeal was effective. Bush not only was the overwhelming favorite among evangelical ministers from the start, but he also carried almost three-quarters of their primary votes and benefited from considerable pastoral activism. Exit polls show that he did almost as well among their parishioners, who gave him a boost in the crucial South Carolina and Super Tuesday GOP primaries. …

Once his nomination was secure, Bush moved again to broaden his religious base, reassuring mainline Protestants that he was not a prisoner of the Christian right. Although he rejected softening the GOP’s strict anti-abortion plank, he insisted that pro-choice Republicans were welcome in the party. He avoided anti-gay pronouncements and signaled that there would be gay appointees in his administration. In touting faith-based programs for solving social problems, he talked more about the poor than is typical of GOP nominees. This was designed to attract religious minorities, such as African American Protestants, and Catholic traditionalists, who find the staunch economic individualism of evangelical Republicans out of tune with Catholic social teachings. The GOP convention itself was replete with highly visible roles for African American Protestant and Catholic clergy. During the fall campaign, Bush stressed broad ethical themes, asserted that America would benefit from spiritual renewal, and repeatedly featured the benefits of faith-based social programs.

Did Bush’s religious strategy work? Obviously, it did not provide him with a comfortable popular vote majority but, together with the religious counter-campaign by the Gore-Lieberman ticket, it probably did enhance the impact of religious forces on the outcome. Many careful observers have argued that the 2000 presidential vote was defined by cultural rather than economic divisions. News magazines printed red and blue electoral maps, vividly depicting Bush’s dominance of the cultural “heartland” versus Gore’s majorities on the “postmodern” coasts. “So what is it that divides the two nations?” asked political analyst Michael Barone. “The answer is religion.” …

One-third of Bush’s votes came from evangelical traditionalists, reflecting their large numbers, strong GOP preferences, and high turnout. Indeed, the entire evangelical community (about 25 percent of the public) supplied almost 40 percent of Bush’s votes. Add mainline and Catholic traditionalists, throw in the Mormons, and the total for theological conservatives rises to 60 percent. (And Bush got a few more traditionalist votes from minorities, such as Hispanic Pentecostals, Orthodox Jews, and some Muslims.) Much of the rest of his total came from mainline and Catholic centrists. While theological modernists, religious minorities, and secular voters formed only a tiny part of the Bush coalition, they dominated the Democratic vote, both for Al Gore and for the Democratic legislators Bush would confront in Washington. …

Like Bill Clinton, George W. Bush had to negotiate the shoals of cultural and religious conflict in the United States. And like Clinton, Bush had an almost intuitive understanding of parts of the American religious community and was a quick learner about others. And even more than the case with Clinton, Bush’s private behavior, public rhetoric and policy proposals were infused by religion. The president’s electoral base was rooted in a coalition of theological conservatives from the three major white Christian traditions, especially evangelicals. His campaign promises and policy initiatives were designed, in part, to solidify his base, while extending the GOP’s appeal to Catholics, as well as Hispanic and African American Protestants. In office, Bush exhibited a deft touch dealing with issues crucial to his traditionalist constituency, such as abortion, satisfying many of their expectations without alienating other religious groups. In the short term, however, he was unable to execute his “expansionary” policies, such as the faith-based initiative and educational vouchers. Solid Democratic resistance in Congress, divisions among his traditionalist supporters, and skepticism on the part of religious leaders in the targeted minority religious communities stymied his efforts.

Bush’s religious strategy was, of course, affected by events unforeseen when he took office. Just as Clinton benefited from economic prosperity that kept his ratings high even in the midst of impeachment battles, Bush’s popularity was sustained by the international conflicts dominating the national agenda after September 11. That popularity largely overrode the normal Democratic propensities of several religious constituencies, at least as long as terrorism and the war in Iraq headed the national agenda. That popularity provided a boost for Republican congressional candidates in 2002, but the Bush religious coalition did not guarantee a national majority for Republican presidential candidates, as the 2000 election had demonstrated. This was especially true if a stagnant economy replaced the war on terror as the main focus of attention. In that event, even the traditionalist coalition backing Bush’s economic policies would be attenuated and his support among religious minorities and secular voters would plummet. Should an economic recovery occur by 2004, the president would still have to go beyond his religious base and pursue an expansionist religious policy, focusing on the very same religious groups targeted in 2000. He would seek to extend his modest success among white Catholics to Hispanic Catholics and Protestants and, perhaps, to still-suspicious African American Protestants. The president and his adviser Rove gave every indication of following that strategy as they planned Bush’s legislative agenda for the fall of 2003 and his presidential campaign in 2004.

The best-laid campaign plans are often upset by unexpected events. The Supreme Court’s 2003 decision striking down state sodomy laws and the subsequent decision of the Massachusetts Supreme Court striking down restrictions on same-sex marriage evoked a massive reaction among religious conservatives that threatened to raise these questions to the forefront of the public agenda. Such issues, which Bush had always soft-pedaled, seem tailor-made for dividing traditionalists and centrists within the GOP and potentially reducing the party’s appeal to independent voters. If traditionalist forces mobilize to protect traditional understandings of marriage, whether through statute or constitutional amendment, the Bush administration faces the inevitability of either disappointing core supporters or forfeiting the middle ground. An unexpected vacancy on the Supreme Court would raise similar problems. In any event, whether the election in 2004 brings a focus on economic issues or foreign policy or a revival of hot-button social issues, the Bush administration’s actions will be shaped in part by religious forces.