In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

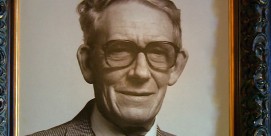

D.A. Carson Extended Interview

Read more of Kim Lawton’s interview with Trinity Evangelical Divinity School professor D.A. Carson, author of BECOMING CONVERSANT WITH THE EMERGING CHURCH (Zondervan):

What are your main concerns about the emerging church movement?

The movement is enormously diverse, and I really don’t want to come across as just panning it. Part of it is concerned with reaching people who are often disenfranchised from what the Bible says or from Christians, and for this sort of concern the emerging people should only be praised, in my view. On the other hand, some are so eager to make adaptations to fit what is understood to be the postmodern mind, or the sensibilities of the so-called “Y Generation,” sort of under 25, under-30-year-olds, that parts of what the Bible actually says get shifted to the side. And so what comes across is not, sometimes, the historic Gospel that you actually find in the Bible. If you start losing the good news about Jesus, then the price is pretty high.

Could you give examples of that?

Well, for example, the historic good news of the Gospel right across the centuries has always been concerned not only with excellent relationships and who God is and turning from that which is evil, but it has also been concerned to confess certain things as true. And the opposite of these things, then, is not true. But some in the emerging movement so influenced by postmodern sensibilities find any mention of truth, objective truth, angular or offensive. It might sound intolerant, and so people like to talk about Jesus himself as the truth, so the truth is relational. Well, I want to talk about Jesus as the truth, too. But the same Gospel, the Gospel of John that portrays Jesus as the truth — the truth made flesh, as it were — also insists that certain things are true, and without them the whole good news about Jesus and what he’s done and why he came and how he actually transformed us gets lost somewhere in the shuffle. So, the Gospel itself is angular. It always has been. It always conflicts. It always challenges every generation. It challenges different generations in different ways. But it can never be — it should never be simply domesticated to the current sensibilities.

In your book you outline concerns about how some in the movement handle the notion of “truth.” What are your concerns when some say, “We’re limited human beings, so we may not have the right understandings of truth”? Are there some things we can be certain of?

It is important to say that we can never have the knowledge of God, what might be called an omniscient access to truth — that is the access to truth only a mind that knows everything can actually have. Postmodern sensibilities have, in fact, helped to remind us that we can only know things as finite human beings can know things. But if you set the bar for the possibility of talking about knowledge at the level of omniscience, of actually being able to know something perfectly and absolutely, the bar is just set too high — it’s unrealistic. I’d want to say that human beings can know things not with the certainty that belongs only to God, but with all kinds of degrees of certainty on which you base your life — the kinds of knowledge that are appropriate to human beings. Paul goes so far, for example, when he’s talking about the resurrection of Jesus, as to say, “If you believe that Jesus rose from the dead” when, in fact, he didn’t rise from the dead, under the assumption now that it was made up or something, “then your faith, far from being commendable, is useless, it’s vain. In fact, he goes so far as to say, “You are of all people most to be pitied if you are believing something, no matter how sincerely, that isn’t true.” In the Bible, genuine faith is increased and multiplied by the articulation in defense of truth. If instead you try to make faith merely a sort of existential leap — a kind of “I want to join this community because the benefits seem to me to be good. I will confess the kinds of things this group confesses, without any claim about whether this sort of thing is true,” one is leaving an awful lot of the New Testament behind. The price is simply too high to pay.

In your book you are also very critical of some of the theological discussions going on within the emergent church movement. What troubles you?

A very significant percentage, probably the majority of the leaders of this emerging movement — they prefer to call it the emerging conversation rather than the movement — are folk who come from a culturally pretty conservative background, most of whom have not had much significant biblical or theological training, but who have been part, in the words of [Brian] McLaren — it’s a lovely expression — on the most conservative twig, on the most conservative branch of the evangelical tree. And then they found this cultural location so narrow or so disassociated from the culture, so removed from where things are happening in our world that eventually they jumped off. They sort of jumped onto a vine and swung to another part of the tree. There’s been a pendulum swing away from things. Instead of finding how to reshape things in the light of what the Bible actually says, using the Bible as the norm, the thing that actually establishes how we should live and how we should think and what we should teach, how we should interact with each other, there has been a kind of pendulum swing to another part, away from this conservative cultural isolationism to something else.

Now I want to say that thoughtful Christians should, by all means, try to read the culture; in this regard I am thankful for the concerns of the emerging church. But it would be really good if they did a little more serious Bible study, got a little better training and aimed to be in the center of historic confessionalism rather than merely taking what is, sometimes from my perspective, a bit of a pendulum swing.

Do you feel they are not within traditional, historical Christianity? They say every generation must figure out what it is to be a Christian in their particular time.

The movement is so large that I don’t want to answer that with a simple yes or no. Many, many in the movement are certainly in the stream of confessing Christianity but are merely adding a few candles or a bit of liturgy or reshaping how they do corporate worship or having more discussion or whatever and call it “emerging.” … Most insist that the Bible really does think of the devil as being a personal individual. But on the other hand, some within this movement disavow that entirely. Although it is true in one sense that every generation has to work things out from the Bible for itself — I don’t want to deny that; you shouldn’t merely accept formulas from the previous generation — at the same time you learn from other generations, too. It’s not as if all wisdom begins and ends with us. That is leaning too hard on a kind of postmodern subjectivism so that nothing can ever be overturned or refuted or corrected. Whereas even in the New Testament documents themselves there was false teaching that was perceived to be false and condemned as false, even within the first century. In other words, the appeal to work something out afresh, to think it through must be made with a kind of humility of mind that listens very carefully not only to the biblical texts themselves but also listens to what Christians have understood across the centuries and does not too easily leap to the present generation, as if its own accounting of these things [is] a certain kind of independent norm.

What cautions do you have for the emerging church movement as it develops?

One of the things I like about them is their emphasis on being authentic. I think that’s wise. But the authenticity is so often tied, as far as I can see, to their passion for the emerging movement. It seems to me that Christians ought to be passionate, first of all, about Christ and about the Gospel, about the Good News. And then, of course, things have to be worked out in different contexts — whether you’re in an urban setting, or you’re working with old-age pensioners or a Y-Generation crowd. By all means, you’ve got to work things out in a local ministry. But what should characterize Christians is a passion for people because of the Gospel, because of Christ, because of God’s love for us in Christ. If people are passionate about that and then are working out cultural challenges — fine, I can live with that. But as soon as someone begins to assume the Gospel and become passionate about something like the emerging movement, I get a little nervous. It’s not that there are not really excellent people in the movement who really do believe the Gospel, but when you listen to what they talk about, what they write about, what they go to conferences for, it all has to do with emergent profiles and how you do this and that. It has to do with the in-house jargon of this developing movement. Some of them go as so far to say that if you’re not with them, you really are unable to minister at all to this new emerging church, this new generation coming along, which, quite frankly, is a load of piffle. There are some excellent people who are ministering all around the country outside the movement to the people that interest this movement the most.

What I want to see in the movement is less focus on emerging as a category and more focus on the Gospel, because otherwise, if the Gospel is merely the assumed thing rather than the thing about which we are passionate, in another half-generation, another generation, the Gospel itself becomes diluted, even denied. The successors and heirs of the current leaders to the movement will be passionate about the things they are passionate about, and they are being stamped now, it seems to me, by whether they are or are not sufficiently emerging, rather than being stamped by whether they are or are not sufficiently faithful to the historic Gospel.

Do you see this as a fad or as something that will really transform the church?

I think that the movement itself is likely to split. In fact, in some ways it already has. One of the figures, for example, who was instrumental in starting the movement in the early ’90s is Mark Driscoll from the Pacific Northwest. He still is extraordinarily fruitful today in multiplying churches and reaching out to people who are not normally touched by other churches. Hats off to him.

Another segment will continue, more or less, doing what it is now doing — that is, using the “emerging” label as the banner flag around which various people coalesce. And others could easily hive off, and, quite frankly, become cultic and dislocated from historic confessionalism at all.

What is your assessment of the role scripture seems to be playing in emergent theology and spirituality?

Many in the movement use scripture in one fashion or another. But I have yet to see any serious work from this camp, studying scripture closely, thinking of scripture carefully. It tends to be a kind of proof-texting, pick-a-text-to-prove-a-point sort of approach rather than really getting inside a biblical book or a chunk of scripture and thinking it out and bowing before it. In other words, scripture really must have a reforming power in our lives. It’s got to say where we’re wrong as well as encourage us where we’re wounded and forgive us where we are repentant sinners, and so forth. The scripture has a lot of different effects. But one of the effects it must have is to correct us. What I do not hear from this camp is the kind of serious wrestling with scripture that will enable scripture to contradict not only modernism but [also] postmodernism. In other words, most in this camp are so concerned about the evils of modernism that they cannot see any dangers at all in postmodern trends in the culture. Or there are very slim and slender dangers that are admitted by way of concession.

In your book, you call some emergent thinking “theologically shallow” and “intellectually incoherent.” Why do you think that?

Let me give an example. Two or three or the authors in the movement, for example, when they come to try to understand afresh what Christ accomplished on the cross, proceed by listing some of the ways that Christ’s cross work has been understood in the past. For example, some have understood what’s called the “Christus Victor” theme, that is, Christ overcomes; he’s the victor over sin and death and so forth. Another is that he is in some ways our representative. Another is that he provides a model for absorbing the guilt and penalty. It becomes the model for the way he should live. And still another is that he is our substitute. He bears our death. He bears our penalty. He takes our place and we are permitted to go free. That’s why God has accepted us, because Christ has died in our behalf. Now the way this is regularly set out is something like this: Here we are in the history of the church with these various models. They each have strengths or weaknesses. Pick one. Pick two, if you like, and see how they fit in to where you are in your life and live it. Well, I want to argue that is usually a bad use of history … That simply isn’t biblically informed. It’s not being informed by scripture. It’s got a shallow approach to the history of doctrine, in the sense that it’s a theologically shallow pick-and-choose sort of approach rather than trying to bring everything so far as we possibly can for the test of scripture.

One of the hallmarks of the movement is that it doesn’t want to have preachers from a pulpit or a professor’s desk telling Christians what to believe. Shouldn’t Christians wrestle for themselves with a lot of these issues?

Sometimes the problem is the way it is set up, as it were. No one believes more strongly than I do that every Christian should be a theologian. In that sense we all need to work it out. I want all Christians who can read, to read their Bibles and to read beyond the Bible — to read the history and theology. By all means read, read, read and, in that sense, interact. I don’t want a kind of priestly class of scholars or pastors or theologians who somehow give dictates to the church about what must be believed. One of the great emphases, in fact, of the Reformation is the so-called universal priesthood of all believers. I certainly don’t want to give any impression that I have some sort of inside access to God that others don’t have or can’t have in principle. On the other hand, clearly some people know more than others or live longer, study Scripture more, or the like. After all, that is what these leaders of the movement must think, the way they keep writing books and telling the rest of us what we should be believing about the relationship between the Bible and movement. There are degrees of seniority and experience. What is passed on should not be in a sort of dictate fashion and “You believe this because I said so. You obey me because I’m up and you’re down.” On the other hand, there are many, many ordinary pastors and teachers of scripture who convey something of the truth of scripture with enormous personal warmth and humility of mind even while themselves conveying something of the authority of scripture itself. This is God’s self-disclosure in words. God is a talking God, and thus you must come to wrestle with him. You must wrestle with what he said. And insofar as pastors or preachers or teachers are seen actually to be faithfully representing what is given, then eventually people are not arguing with some authority figure. They are arguing with scripture itself. Of course, I want Christians to wrestle like that. On the other hand, precisely because not everybody is as mature, as informed, as well read as others, this does not mean that every opinion has equal weight in terms of the kind of influence it should have in the church.

There needs to be a place in the church or just outside — there needs to be a place where people feel free to ask questions without being put upon, where they feel free to ask difficult, challenging questions to voice their skepticism. All of that’s necessary; I couldn’t agree more. On the other hand, there also needs to be a place where more senior Christians are teaching more junior Christians. Come see for yourself. Read, read. Find out these things for yourself. Grow, grow. There is some material here to learn and not simply give your opinion about.

Are young people today looking for a place to ask spiritual questions or to find answers?

There’s often a sort of stereotype to the Y-Generation or postmodern people that they can’t stand any authority. In fact, it’s even arguable that there’s even a swing back in university student profiles and elsewhere — there’s a kind of suspicion of people who are so endlessly open that they can never articulate anything. In fact, I’m neither a prophet nor a son of a prophet, but it wouldn’t surprise me if there were a kind of a cultural swing to the right on some of these issues in the next 20 years. But whether that’s the case or not, there is always a segment of the population, even in very fluctuating times, that because the times are fluctuating want a little more stability and structure and order. … Ultimately, if you try to weigh and evaluate and think without having the grist for the mill, it just becomes a pretty empty-headed discussion.

Is it possible to generalize about the emerging movement, since it is so diverse?

One of the reasons why it is difficult to evaluate the emerging church movement fairly is because of its diversity. Some people, especially if they have come from conservative backgrounds, have found themselves disenfranchised in their ability to talk with ordinary people. They’ve picked up some tips from some of the emerging leaders, and so they think of themselves now as part of the emerging movement. Basically, they’re simply ordinary Christians who have just learned a little bit better how to talk with people who aren’t Christians and who live outside their own contextual Christian culture. That’s all to the good as far I’m concerned. On the other hand, as the emerging tag becomes stronger and stronger, then sometimes they become a little more interested not in actually winning other people to Christ as [in] winning other Christians to the emerging flag. That becomes a little more troubling. And then you keep moving farther out and farther out and farther out until the whole cultural shift that is sometimes characterized by the label “postmodern” begins to domesticate what the Bible is actually about. At that point it becomes more than troubling. It becomes really a threat to historic Christianity. All of it still flies under the label “emerging,” and so you can go to a major emerging conference and all of these different voices are speaking equally. If you criticize someone for example at, oh, we’ll call it the far left end — although it’s not really a left and right sort of thing — at the more skeptical end of things, at the postmodern end of things, at the more open-ended end of things, you criticize someone along those lines and say, you know, I’m a little worried about just where this is taking us, there’ll be a whole lot of people at the other end of the spectrum saying, don’t put me in that basket. I’m as strong a believer in what Christ has done for us as you are.

But nevertheless, for both groups, the emerging flag becomes a little more important than the Gospel itself, and that eventually begins to trouble me.

You’ve said some wings of the emerging church are posing a threat to traditional Christianity. Is that really the case, or is it overstating the case?

Christianity itself is far more stable than something that can be shoved over by a movement. Christ himself said, “I will build my church and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” God is not going to be threatened by any movement in this century or any other century. The church in that sense has withstood wars and persecution and attacks and its own seductions and stupidities. It’s not going to be overturned by a movement, so I don’t want to say that. All I’m saying is that those who get sucked into the far-out end so that accommodation to postmodern sensitivities, a refusal to deal with the category of truth, a refusal to say that, according to the teachings of Jesus, some things are right and some things are wrong, that there is an objective truth, propositional truth to be announced as well as discipleship to Christ to be lived and displayed, and authenticity is delight in God to be demonstrated individually and corporately, in addition to all of these things there is truth to be announced — if you start losing that, you really step outside what Christianity is. The Gospel is something to be taught and to be believed. It is not something simply to be experienced.

One of the troubling features of the movement is that it is investing so much energy and self-identity in the movement itself and merely assuming the Gospel, rather than investing this passionate energy in the Gospel and in the application of the Gospel to people using genuine cultural insight to learn better how to do it. As soon as the Gospel becomes something that is merely assumed, while the movement becomes its own raison d’etre, its own reason for being, then it is approaching silliness. It is certainly losing the story. A wheel is coming off somewhere.

What’s your impression as you read Brian McLaren’s writings and what he is calling for?

Well, first of all, I want to say that he’s a charmer. He writes well. He writes engagingly. I’ve never had the privilege of meeting him. But I’m sure I would enjoy sitting down and having a drink with him and long conversation. He’s clearly warm-hearted and winsome. So, if I disagree with him on some point or other, I want to say in the strongest terms that he is, as least as I’ve seen him, above being a nasty or a petty or the like, and for all of these reasons I appreciate him. Moreover, some of the questions he raises have to be raised again and again every generation. I’m far from saying that there’s nothing beautiful or interesting or challenging in the book [A GENEROUS ORTHODOXY]. On the other hand, his very niceness can sometimes entice people to come along with the niceness, even if he’s saying something that is not, at the end of the day, really sensible.

What are some of the points that concern you?

Consider his book A GENEROUS ORTHODOXY. The subtitle is impossible to repeat. It’s something like probably 20 or 30 more words [“Why I am a missonal evangelical post/protestant liberal/conservative mystical/poetic biblical charismatic/contemplative fundamentalist/Calvinist Anabaptist/Anglican Methodist Catholic green incarnational depressed-yet-hopeful emergent unfinished Christian”] and in one sense that really fits the postmodern mood, doesn’t it? A pick-and-choose bit that takes a bit from here and a bit from there and refuses to be tied down to any tradition. There’s something really attractive about that in the contemporary culture. But when you actually look at the arguments he makes for why he belongs to this or that camp, sooner or later one becomes — I don’t know how to say it but — gently appalled at the lack of rigor, even the way serious discussions are skated over.

For example, “Why I am an evangelical”: The reason he says he’s evangelical is because he likes evangelical passion. Now notice, he likes evangelical passion, not evangelical Gospel or their historic commitment to good works and service or their relationship to the great doctrines articulated in the Reformation or their worldwide evangelism. It’s the passion. There is nothing distinctive about passion and evangelicalism. Many movements are passionate. The fact that a movement is passionate does not make it evangelical. So for him to say that he is evangelical because he is passionate is simply a non sequitor.

Similarly, when he says that he is Reformed he takes one slogan from the whole Reformation heritage: Semper Reformandum, that is to say, the Reformers thought that the church should always be reforming itself in light of the word of God, and he says in that sense he, too, is Reformed. Well, yes, yes, just about every group wants to be reforming itself in the light of scripture. … The only element that he identifies himself with in the Reformation, to call himself reformed, is he’s always reforming himself. I find this sort of argumentation to be either be cute and clever or, frankly, right on the edge of dishonest. If you claim to be something, you ought to be identifiable as such by at least some others in the party. I don’t know anybody in the Reformed tradition that would think of McLaren as being Reformed. In fact, it’s hard to imagine his definition of being passionate as adequate for being identified as an evangelical in the evangelical tradition, too — the same also with his definition of liberalism and Catholicism and so on. It becomes a slippery way of picking and choosing rather than a way of being, somehow, the kind of person who can put all of these traditions together. At the end of the day, it becomes a very isolated new form of individualism, in which I pick what I want from these things rather than, in fact, belonging honestly to any of them. Instead of being all of these things, he really isn’t any of them but is really becoming his own new identity by picking and choosing among them. That sort of self-focus and self-definition — it’s really right on the very edge of a new form of self-idolatry, isn’t it?

Is part of your problem that it’s hard to tell exactly where he comes down?

It’s not because he doesn’t want to give any answer at all, it’s because he wants to give answers that are fuzzy. That is his intent. It’s not because he is a clever diplomat who is trying to avoid the toughest questions by using ambiguous answers of a diplomatic cast, but everybody who understands the language knows what he really means. He really does want all of these edges taken away. He wants to avoid what he perceives to be the angularity of confessional truth. And he’s very good at dancing around. He’s very good at it. At the end of the day, it seems to me that it avoids some of the angularities of the Bible itself.

He raises the topic of hell and criticizes traditional evangelicals for putting so much emphasis on “personal” salvation. How provocative is this kind of language?

On the personal faith sort of thing, there are segments of the broad evangelical movement where, quite frankly, I share his concerns. It’s often been pointed out — this is really coming to it from the side, but — it has also been pointed out in recent times that when you take out the morals profile of the evangelical movement as a whole — let’s say, divorce rates — that profile, those rates are indifferentiable from the rates of the culture at large, and that can be very troubling. But as soon as you start putting in some filters, as soon as you start saying so-called evangelicals who go to church at least once a week, and who read their Bibles regularly, and who really do confess Jesus as Lord meaningfully, and who want to live under the authority of the Bible, then the morals profiles of that group of evangelicals is hugely different from the profile of the culture at large and of evangelicals self-proclaimed at large. In other words, I would say that the so-called evangelical movement today is so broad that there are all kinds of people who sort of “get done”; they’ve made a personal statement of faith and think that they’re in and they signed a card or they walked an aisle, but [they] really haven’t, in any biblical terms, been regenerate. They really haven’t come to know God. Their lives really haven’t been transformed by the Gospel. Whereas the Bible is very clear that the genuine faith does transform you. It really does change you. Now, if that’s what he’s saying, I’m with him. I’m with him one hundred percent. On the other hand, it’s a bit of a caricature to say that all of evangelicalism is like that. There are some big swathes of it that are, in my view, a long way away from the Bible itself. The Bible must be the reforming agent. But there are also huge swathes of evangelicalism which stress not only that individuals must individually repent and believe but that they join together as brothers and sisters in Christ who constitute a local church, in part of the people of God adjoining men and women from every town and tribe and people and nation. I believe that as passionately as anyone. And many of us do. Yet at the same time, while you’re stressing this corporateness, you still want to say that people have to trust individually. That too is something that is demanded again and again and again in Scripture.

Do people walk away and say, “Brian McLaren does not believe in hell”?

It is worth reminding ourselves that the person who speaks most often about hell in all the Bible is Jesus. I know that there are very clever attempts to domesticate what he says, but it really is hard to avoid the angularity of his insistence that there is a heaven to be gained and a hell to be feared. Now that does not mean that Christianity is only for the life to come and is not for this life. That’s simply isn’t the case. And it does not mean either that most Christian preachers of the traditional camp spend all of their time warning against hell. In fact, in my judgment, broader evangelicalism today is so diluted on what Jesus himself actually says about hell that there aren’t many serious warnings at all, even from within the traditional camp. The day when people were so heavenly-minded there was no earthly good — if it ever existed, certainly it isn’t today. Nowadays we’re so earthly-minded that we’re probably good for neither heaven nor hell.

There’s such a focus on the [contemporary] dimensions of Christianity that the eternal dimensions of being ready to meet your Maker can get lost in the shuffle somehow, but those dimensions are taught by Jesus himself. … And so it is important to capture that dimension or you lose something that is integral to the teaching of Jesus himself.

How provocative is it for McLaren to raise these questions and make suggestions that challenge traditional understandings?

If the suggestions he were making were based on careful, close reading of scripture, and [if he] interacted with people who, similarly, have made close readings of scripture, then it would be simply part of the broader discussion. But, in fact, if he takes people farther and farther away by clever arguments that are not submitting to scripture, then I fear that what will happen [over] the long haul is that he will be disenfranchised. He will disenfranchise himself. In some ways, his theology reminds me very much of a sort of old-fashioned 1920s liberalism, and eventually, I think, more and more people will see that, unless he himself self-corrects, which is still possible.

How should people read his writings, especially those who do not have theology degrees?

Read discerningly. Read everybody discerningly, whether you’re reading my books or his books. Test everything by Scripture. Don’t believe somebody just because they’re nice and write well, or just because they’re scratching where the current culture is itching. Always, always, always if you’re a Christian, come back to the test of scripture, so far as that is humanly possible.

Some evangelical leaders have accused him of being heretical. Is that fair?

Brian is so careful to dance around the edges that he’s shrewd enough not to come into the position where he simply says, “I know that’s what the Bible says, and I disbelieve it.” At some point, when a person does that, then categories like “heresy” are appropriate categories. But he’s so careful not to do that while skirting the same issues, giving the impression that they’re either not important or he wants to reinterpret them, that at some point I understand why those labels are being raised. But with my whole heart I would much rather see him hear these sorts of criticisms and self-correct. Come back and re-read scripture afresh and reform himself in the light of the word of God rather than simply being turfed out too soon, too quickly, as it were. He is helping some people rethink. Do I think he’s saying some dangerous things — dangerous in the sense that he’s diverting people from things that are central to the Gospel, that are nonnegotiable as part of the Gospel — he’s diverting people away from those things? Yes, in that sense, I think he’s dangerous. On the other hand, I hope and pray with all my heart that he will, as he’s made several shifts in his life already, make another one that comes back to the centrality of what the Bible actually says and be more concerned to be faithful to that than to the current postmodern agenda.

To what extent do you think these are lasting ideas or a current fad?

The staying component in what they’re doing is the missional concern to reach a new generation of biblically illiterate people who don’t know any of the theological jargon, don’t know that the Bible has two testaments, don’t know how it’s put together. The emphasis on understanding the culture, reaching out to people — all of those things are hugely important. They have a staying power. They’re part of Christian confessionalism, Christian mission, in every generation. And there are many, many, many Christians outside the movement that share exactly that perspective. In that sense, they’re not nearly as new or as innovative as they think they are. But the bits that are most distinctive in the so-called emerging church movement are, in my judgment, largely ephemeral, because they have been called forth by certain cultural developments, and as the culture changes, as cultures do change, then those things will shift again. I just can’t predict how the shifts will come about, but my guess is that in 50 years, nobody will be talking about the emerging church movement. They will still be talking about the Gospel of Christ.