In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

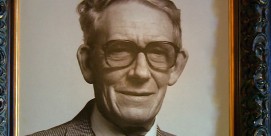

Scot McKnight Extended Interview

Read more of Kim Lawton’s interview about the emergent church with Scot McKnight, religious studies professor at North Park University in Chicago:

How would you describe the emergent church?

It’s a conversation among 20- and 30-year-olds about the direction of the evangelical and post-evangelical church in the next generation. That will focus on local communities and embodiment or performance of the gospel by everybody involved. It’s a reaction or a protest at certain levels against traditional evangelical churches.

What precipitated this conversation?

I think dissatisfaction with traditional evangelical answers to questions that are emerging at universities and [in] the younger culture. I often tell our people that this generation did not grow up with Mr. Green Jeans, they grew up with Mr. Rogers and Sesame Street and the emphasis upon diversity and pluralism and dialogue and conversation, rather than taking hard lines and making firm judgments about people and groups.

So how does that play out in religion and church?

There’s a general recognition, I think, among emergent voices that there should be a conversation among all Christians about what unites Christians, rather than drawing firm lines, denominational distinctives, and emphasizing differences. It’s a post-Catholic form of Catholicism, where they want to be universal and global, but they want to be global and universal at a level of community and practice rather than trying to get into long discussions and debates about theology.

Is this something new and radical, or does this kind of rethinking happen in every generation?

When I first heard about the emergent movement, the emergent conversation — these are profound categories that are being used — it reminded me of the Jesus people of the ’60s and ’70s. But the Jesus people were concerned with a post-Vietnam or a Vietnam phenomenon and were reacting to what was going on in American culture, and I think the emergent conversation is a reaction against a Christian culture rather than simply a social response. So it reminded me of that and no, I don’t think it happens in every generation, but every now and then it does happen, and this has taken hold globally, so it’s not simply a North American-United States-Canadian issue. This is a global response to how Christianity should be performed in our world.

How far are the edges being pushed?

Some traditional evangelicals have responded vehemently and almost with volatility to the emergent movement, because they see a blurring of theological lines that were earned and worked for very hard in the previous couple of generations. Evangelicals fought hard for their own distinctives over and against mainline generations. This emergent conversation wants to knock down those boundaries and engage in conversation across old-fashioned theological walls. I do think there is something very significant at this level of conversation.

And this is threatening to some wings of the church?

It threatens the more conservative evangelical group in many ways but mostly just over theological affirmations and doctrines.

In what way?

They want to open up questions. They’re asking questions about how we should understand our relationship to scripture: Is it inerrant? Is it true? And many of the emergent people are saying that it is the senior partner in the conversation, which is a healthy category. They’re asking questions about what we should believe about the afterlife. They want to ask questions about heaven and hell. They want to challenge some of the traditional Christian views on these questions. They’re very big on how to “do” church, which is not an expression that I prefer, but they are big on how the church should operate as a community of faith.

The emergent voices want to ask whole new sets of questions, answer these questions in new ways and work out church in this generation. And the final [question] and perhaps the most explosive one has been: How certain can we be about what we know? Many of these emergent voices are less certain of their theological ideas, and this appeals to a generation that is given to dialogue and to discussion and to conversation, and not making firm judgments about people.

Why is that so controversial in some parts of the church?

In the conservative evangelical wing, scripture forms the foundation for truth, and insofar as we know what scripture says, we know the truth. This has been challenged by the emergent conversation because they are saying that what we know is what we think we know, rather than what is to be known. There is a recognition that we as subjects, as knowers, influence what we think we know. Involved in this also is the belief that truth is a relationship and a life or a performance of the gospel. It is action. Truth has moved out of the realm of just what we know to who we are and how we exist as a community.

How have some conservatives reacted to that?

Several of the major conservative evangelical leaders have contended that the emergent leaders have denied the possibility of knowing truth. When significant leaders make strong pronouncements that this is dangerous or it borders on heresy, there are many people who will listen to that voice. There is a general concern about how viable, how reliable and how firm the emergent conversation really is.

How widespread and influential is the emergent church movement?

The instincts of our current generation of teenagers, 20s and 30s are in line with the instincts of the emergent conversation: dialogue, conversation, debate, respect one another, tolerance, diversity. These are the instincts of the emerging conversation.

How diverse is it? Why is it so difficult to define?

The emergent conversation is difficult to categorize because it is focused on local expressions of the gospel tied to local culture. Depending on the environment, the neighborhood, the specific culture in which an emergent conversation begins will completely shape how that local expression of the gospel works out. So it can’t be simply defined; it can’t be simply categorized, and it’s causing no end of frustration for people who would like to have tidier boxes. This is the way they want it, because they believe the gospel should have a local expression. It should be extremely different in different places because cultures are different in different places.

Emergent conversation is going to vary in different ways to the degree that a local group of people decides to embody it all. Some of them are radically emergent, some of them are moderately emergent, and some of them are just — there’s a whiff of emergence in what they have to do. It reminds me in many ways of how the seeker movement began to impact churches.

Talk a little about the categories they use. They call themselves post-modern, post-conservative, post-liberal, post-evangelical.

It’s a recognition of the postmodern context of our world. Theologically, they are not evangelical or anti-evangelical or moderate evangelical. They believe that evangelicalism and mainline denominations and even Roman Catholic churches, even Orthodox churches, are an expression of a modernist impulse. As we move beyond or become postmodern, we will also become post-evangelical, post-mainline because those distinctions were based largely on theological differences rather than practical performances. And in the postmodern church, they are concerned with performance-based faith. It’s all about mission, how we live out the gospel in our world. This will allow churches and Christians to unite.

Most of the emergent churches are post-evangelical rather than post-mainline. Evangelical churches defined themselves theologically largely, and they did so with doctrinal distinctions that sealed them off from mainline denominations, that distinguished them from mainline denominations. The emergent church is concerned with knocking down those boundaries, so it becomes post-evangelical in the sense that “that’s the way we used to do things.” We no longer do things that way now. We have more of a conversation and a dialogue than a robust debate where we draw lines and divide ourselves off from one another.

What are some of the big challenges that face this movement?

The biggest challenges that the emergent conversation is facing is whether it will be truly evangelistic and reach out or whether it will be, at times too often, disaffected evangelicals getting together to be disaffected; whether it will be genuinely global, whether it will be genuinely diverse, attracting people who are not just of one ethnicity or one intellectual level or one economic makeup but one that will minister to an entire neighborhood in all different kinds of contexts.

I think that one of the major issues for the church is going to be whether the emergent conversation becomes genuinely theologically coherent. Right now, a lot of people have trouble figuring out what this is all about, and until that answer comes — what is it all about? — there will be people who will simply not write their name on the line. The church has always defined itself on the basis of some of its theological commitments — its creeds and in Protestantism, what took place in the Reformation. Until this emergent conversation does draw a few lines in the sand so people know where they are, there will be challenges.

The emergent conversation is being challenged by traditional Christian groups to articulate its theology. What do you believe is a question being asked, and until the emergent conversation and its leaders articulate its theology at some level — this is what we believe, this is what we don’t believe — then the church will not take notice to the degree that it perhaps should, because the church always has articulated its theology. We expect a local church to say what it believes and what it doesn’t believe, and it will have to define itself in its own way. We’re not asking for every emergent church to have a 55-point theological set of affirmations, but instead to affirm what you believe about theological ideas.

They like to say it’s not about finding answers, it’s about asking questions. But is there a point at which a faith group needs to offer some answers? Do questions alone sustain spirituality?

This is a good question, and it’s an important question for emergent leaders to consider. The emergent conversation and its leaders recognize that the church has traditionally defined itself by creeds. They are worried about how many lines of creeds we have to affirm because they believe that genuine Christian spirituality is action and life and community and performance and embodiment rather than simply the affirmation of certain doctrines. I understand that many of them want to ask good questions, but for things to be Christian, to hold scripture as the senior voice in a conversation means that there are answers and there are limits to what those answers can be.

Is the push for institutionalization also a big challenge for folks who don’t even like to call themselves a movement?

There are so many people now interested in the emergent conversation that it will not be possible to stop some levels of institutionalization. We know how groups and churches develop. They begin informal; they begin at the level of community and relationships and friendships. It’s small. People know one another, they know they’re ideas, they trust one another. But as a group grows it has to institutionalize, develop lines of authority, lines of leadership, and when they don’t develop that, they generally fall apart. Right now the emergent conversation has found itself so big so fast that there has to be some institutionalizing process going on. But I hope they keep some of the informality, because it allows freedom and growth and new ideas to take place.

How influential has Brian McLaren been in all of this?

What I like most about Brian McLaren is he’s asking hard questions and he’s not letting people get by with shallow answers. He’s forcing conversation about topics that are sacred cows in the evangelical church.

How controversial within the evangelical world is it for Brian McLaren to be raising questions about hell and the afterlife?

Most evangelical Christians have a view of hell that came out of Dante’s Divine Comedy and out of categories and images that they heard from pastors and preachers. Brian McLaren has [asked], what was the rhetorical function of this literature in the Bible and is it really describing the afterlife? Can we imagine fire or should we imagine that this is rhetorical language about separation or pain or a less than noble state in the presence of God? Brian is asking a very difficult question. He’s challenging evangelicals to look at their Bible again, to see what it really does say and how much of it is myth and how much of it is straightforward description of the afterlife. It’s a good question to ask.

And how provocative is it for him to be asking it?

It’s so provocative because it challenges the foundation for many people and the reason for preaching the gospel, because it’s about eternity. McLaren is saying the focus of Jesus, the focus of the Bible is on life in the world as we live it here and now rather than heaven, whereas the evangelical gospel has very often been, “Jesus came to earth to die for my sins so I can go to heaven.” The rest of the world really doesn’t matter that much. And McLaren is saying no, that’s not what Jesus taught. He’s trying to get people into a conversation about a powerful subject that lies at the heart of what many people think the gospel is about. I think he has been a masterful success at getting a conversation going, and I think this is a conversation worth having.

How important has the Web and blogging been to this conversation?

The emergent conversation is essentially a theological conversation. Theological conversations in the past have taken place in books and magazines and articles. The emergent conversation is taking place in books, in conferences, but especially on blogs and Web sites. You can’t become conversant with the emergent conversation until you get on the Web sites and start reading the blogs. Tall Skinny Kiwi, Theoblogy — these are important blogs that people go to to find out what’s being said and what the conversation is going on now. I had a conversation with an emergent-type pastor the other day who told me he subscribes to 250 blog sites. I didn’t know there were that many. This is not a conversation that is taking place in a traditional way. If you think you can go to the bookstore and check out the most recent book and find out what’s going on, you’ll miss 90 percent of the conversation, which is essentially a grassroots, democratic, electronic and interpersonal conversation in local churches.

Is this conversation all that different from past movements within Christianity?

The emergent conversation operates more in theology than in the past. In the past, the evangelical conversation and theology take place by believing in the total doctrine of scripture so that all of scripture must be mined to find out what we are to believe. The emergent conversation says we begin with Jesus, and everything else is secondary to what Jesus says in his vision for the kingdom. And it’s not just what Jesus says, it’s the community around Jesus, it’s the practices of Jesus, it’s the relationship to Jesus that gives rise to all other theological reflections. They’re trying to figure out how to live the gospel in our culture today, as other Christians have always tried to work out the gospel in their generation. But they are so self-conscious about the culture and how to relate to that culture that there’s a sharper knife and a deeper perception than some generations that simply absorbed the culture in previous eras.