In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

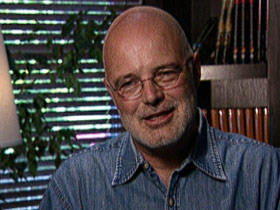

Brian McLaren Extended Interview

How do you describe the emerging church?

It is a group of people who are trying to put together two things that have been apart. One of them is a fidelity to the Christian message, and a real concern about it actually being lived out in practice. And we’re saying you can’t have one without the other.

How does that work itself out in the way congregations and communities look and act?

When you try to put those things together, you end up with a stronger emphasis on practices. It’s not just doctrines that people get in their minds, although our thinking is very, very important. But also there is a desire to have practices that actually form us as people. What’s interesting to me about this is [that] this trend of emphasizing practices and a lived faith is happening across the spectrum. Roman Catholics, mainline Protestants, evangelicals, charismatics — many people being drawn together by this common emphasis. Then when you are emphasizing personal transformation and the experience of God and learning to actually live in a relationship with God from day to day, I think when it really gets exciting is when that works out in the social sphere. When we start saying this means the way we treat our neighbors; the way we treat people of other races, religions, social classes, educational backgrounds, political parties; the way we treat other people and interact with the environment, and all the rest is part of our spirituality. When that happens, when those things get integrated, I think that’s the makings of a very exciting spiritual life and movement.

How did all of this get started?

Well, back in the early 1990s there was an organization called Leadership Network funded by an individual in Texas, and Leadership Network was bringing together the leaders of megachurches around the country. By the early and mid-’90s, they noticed, though, that the kinds of people that were coming to their events were getting a year older every year, and there wasn’t a [group of] younger people filling in. They were one of the first major organizations to notice this.

They started realizing that there was a sentence that was being said by church leaders of all denominations across the country, and that was, “You know, we don’t have anybody between 18 and 35.” When they started paying attention to this increased dropout rate among young adults in church attendance, that opened up a discussion in the mid-’90s about Gen X. And so they starting bringing together young leaders in the Gen X category to talk about what was working in the church, what wasn’t working, what was going on.

After a couple of years some of these young Gen X guys said, “You know, it’s not really about a generation. It’s really about philosophy; it’s really about a cultural shift. It’s not just about a style of dress, a style of music, but that there’s something going on in our culture. And those of us who are younger have to grapple with this and live with this.” The term that they were using was the shift from modern to a postmodern culture. And so what began to happen — and as this thing had a life of its own, they said, “If it’s not just about Gen X, then we have to make sure that we get some older people who aren’t just in that age frame to talk about this.”

I had just written a book on the subject. That’s how I got involved, and it turned out that there were a number of us, all simultaneously thinking we were the only one talking about it and thinking and writing about it, who all around the same time were noticing the same phenomenon. So it was a very exciting coming together of these younger leaders and some of us a little bit older, saying, “This is our world, and this is the future. And the Christian faith and our individual churches, we’ve got to engage with and deal with it.”

Talk a little bit about what you see as some of these shifting cultural contexts that may be the hallmarks of this world that you’re trying to engage.

It is very hard to work with definitions of words like “modern” and “postmodern,” because different people use them in such different ways. And so if anybody assumes when one person uses the word “postmodern,” the other person means the same thing, it just creates all kinds of communication problems. But maybe here would be a way to say it. In my travels, where I speak and where people talk to me about my books, they say to me again and again, “The people who are the normal spokespeople for the Christian faith don’t speak for me. They don’t represent me.” There is something under the surface that they can’t quite put their words to. But they say, “That approach to faith is not my approach.” Now sometimes it’s political; it’s related to the religious Right and some of that rhetoric. But I think it’s not only the political side; it’s also a way that we engage with other people. It has to do with authority. I think, to some degree, there is a tendency that is inherited in the church for people to say, “Look, you already ought to agree with me, and if you don’t, you’re wrong. And so you better straighten up and fly right.” Whereas I think for those of us dealing in a more postmodern context, we realize it’s not people’s fault they don’t already agree with us. In some ways it’s our fault, because we haven’t done such a good job of a) living what we believe and b) explaining it in very sensible ways. So our approach is much more conversational and much more, maybe you could say, horizontal rather then top down.

What are some of the characteristics of the cultural context? What is it about the kind of culture that we have today in contemporary Western society?

Whenever we talk about the Christian faith engaging with culture, one of the temptations is that people feel that we’re sort of dumbing down, that the church is up here and the culture is down here, and we’re dumbing down our message, or we’re compromising, or lowering our standards to sort of match. That’s not what any of us are talking about. What often we hear is that people are saying, “Postmodern culture’s way down here, the church is up here, and you’re saying bring us down.” We’re saying, “No, actually what we think happened is that modern culture has been, in some ways, spiritually an arid place. It’s been spiritually a place that there wasn’t much room for authentic and communal spirituality. And so modernity brought us down.” We think that the church has, in many ways, already accommodated to modernity. And so the Christian message has become a product almost, and it and the methods of spreading it are like sales pitches. We feel that it has been individualized. It’s almost like we have personal computers, and now we have personal salvation. And there’s not so much attention to what’s going on in our world. What about the social dimensions of our faith, that sort of thing? What we’re trying to do is say, “We’ve already overaccommodated to modern culture. We’ve commodified our message; we’ve turned our churches into purveyors of religious goods and services.” And we’re saying, “No, how can faith in some ways break free from that to engage the issues that we believe the Christian gospel challenges us to?” And those are issues of loving God with our whole heart, mind, and strength and loving our neighbors as ourselves, which has profound implications on everything from ecology to racial reconciliation to how we spend money in our personal budgets and the national budget and that sort of thing.

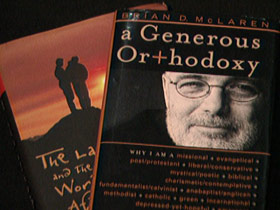

In GENEROUS ORTHODOXY you raise a provocative question: “If Jesus were physically on earth today, would he want to be a Christian?” Would he?

Well, in the book I give kind of an equivocal answer. But the question, I think, is really, really a worthwhile question. For example, there’s been huge interest in the last couple of years in THE DA VINCI CODE. Now what’s so interesting is THE DA VINCI CODE explores a radically different picture of Jesus than the church has portrayed. But it’s fascinating that for millions of people, that picture of Jesus is actually more interesting and intriguing and in some ways morally compelling than the image that they feel they’re given by the church. I’m not saying I endorse THE DA VINCI CODE image at all. But I am saying that people feel a huge disconnect between the image of Jesus that they get from reading the Bible and the image of Christianity they get from the media, whether it’s in its more institutional forms or in its more grassroots forms. They just feel that those two don’t match. What I think many of us are concerned about is, how can we go back and get reconnected to Jesus with all of his radical, profound, far-reaching message of the kingdom of God?

I think it would be safe to say that everything we’re doing with the emerging conversation is summed up in saying, “What is the message of Jesus, and what is the message of the kingdom of God? What does that mean?” In many ways, what we feel has happened is the church has tended too often to be about institutional survival, which results in horrible things, from fund-raising scandals to covering up pedophilia scandals. When institutional survival is the purpose of the church — Jesus said it: “If you save your life you lose it. You can gain the world and lose your soul.” So the church starts to lose its soul. The church has been preoccupied with the question, “What happens to your soul after you die?” And that has resulted in, all too often, an abandonment of the ethics of the kingdom of God, the ethics of Jesus for this life and our history here and now.

In GENEROUS ORTHODOXY you’re pretty critical especially of the evangelical focus on personal salvation. Why does that trouble you? That is one of the basic concepts in many people’s theology in the evangelical church.

Well, first of all, I’m not at all against the idea of a personal relationship with God. I think that’s where it all begins. I think this is part of the beauty of the message of Jesus. Every individual is invited into a personal relationship with God. But personal is not private, so personal doesn’t just mean it’s me and God, or me and Jesus, but personal means that my connection to God also connects me to other people and connects me to what God is doing, the mission of God in our world.

When we end up in some ways commodifying and privatizing faith, it in many ways marginalizes faith and makes faith be either like a consumer product or like a personal preference. Or it makes us just be a demographic group that gets marketed to or manipulated by political parties or whatever else. But if people believe, as I do, that our Christian identity actually thrusts us into the world with a sense of mission, and it gives us a concern for the poor, it gives us concern for justice, all these very, very important things in our world today, the reconciliation with our neighbors and our enemies — if we believe we’re thrust into the world in this way, then our faith doesn’t just stay personal and private. It then engages us in the world.

You know, you could look at it like this: if becoming a Christian makes a person withdraw and isolate so that their focus is on what will happen to [them] after death, and makes them less involved in the problems and needs of this world here, today, every person who becomes a Christian in some ways is taken out of the game. But if being a Christian means converting from being part of the problem to being part of the solution, then every person who is a dynamic, growing Christian is engaged in the world as an activist on the cause of justice and peace.

Talking about this focus on what happens to your soul after death brings up the question of heaven and hell, which is very controversial. Your newest book also focuses very much on these things as well. I’ve talked to some folks who come away from reading your books saying, “Brian McLaren doesn’t believe in the traditional view of hell anymore.”

Well, you know, one theologian just wrote a review of my newest book, THE LAST WORD AND THE WORD AFTER THAT, and I thought he was very fair and very accurate. He said that my purpose in the book is not to demolish an old view or replace it with a new view. My purpose is to get conversation going about the old view and problems with it so that we can together move forward in reconsidering, and maybe there is a better understanding of what Jesus meant and what the scriptures mean when they’ve talked about issues like judgment, justice, hell, heaven, that sort of thing.

The way I’ve tried to describe what I’m trying to do is this way: let’s say you’re going down a road and you come to a T in the road. And there’s a sign, and it says if you turn left you get to Boston, and if you turn right you get to New York City. And I get to that T and I think, “You know what, I actually want to go to Los Angeles.” At that moment, my answer isn’t to turn left or to turn right, my answer is to turn around and rethink how I got to where I am now.

I think we’re in a similar situation in not just evangelical Christianity, but really in Western Christianity — that for a very long time we have been very preoccupied with the question, as if the reason for Jesus coming can be summed up in “Jesus is trying to help get more souls into heaven, as opposed to hell, after they die.” I just think a fair reading of the gospels blows that out of the water. I don’t think that the entire message and life of Jesus can be boiled down to that bottom line.

What is it about the traditional concept of hell that bothers contemporary people or that has brought us to this point?

There are so many different problems, I think, that come up with this. But one of the deepest problems is that — and nobody ever would intend this — but that for some people the traditional view of hell makes God look like a torturer. It makes God look like somebody who just can’t wait to torture you for everything you’ve done wrong. And then you sort of have this dark view of God and then maybe a better view of Jesus, because Jesus comes in and in some ways saves you from this dark side of God. But I’m very convinced by … the example of Jesus, the life of Jesus. He says, “God isn’t like that, God is like a father who loves His children.” Now that doesn’t mean that God says, “Oh, everything’s fine, whatever you want do is okay. Just have a good time,” because I’m a father and when my children would beat each other up, I’d be upset about that, you know. But I didn’t want to torture the one who did the wrong thing, I wanted to stop them from hurting their sibling and I wanted to teach them to change, so I think simultaneously we have to deemphasize this image of God as a torturer, but we have to raise our understanding that God cares about justice. And that suddenly comes home to those of us who are very religious, who are praying and singing, “God bless America.” God bless us. We’re already the richest, most powerful nation in the world, and we’re just saying, “God bless us more.” We’ve already got more weapons then anybody else, we’ve got more security than — “God bless us more.” Well, if we believe in a God of justice, at some point we’ve got to think, “If we’re so blessed, maybe we ought to be caring about the people in Darfur, the people in Eastern Congo, the people in the Middle East who are suffering this ongoing trouble.” And we ought to say, “How can we be agents of peace and reconciliation and rescue and help and service to other people, instead of just being preoccupied with our own blessing?”

That to me is very related to a view of a just God. And I think that there is some absolutely unintended collusion between a preoccupation with evading justice after this life and ignoring justice in this life. Now that’s not universal and it’s not intended, but it’s an unintended consequence of what I would say is an overemphasis on hell.

Many people are frustrated by that answer because they want a straightforward answer, and you don’t seem to enjoy giving straightforward answers.

Well, you know, a couple people tell me they think I’m being evasive, they think I’m a coward, I’m afraid to say what I really think. But here’s the interesting thing. I don’t think I’d be saying what I’m saying if I was a coward. And what I’m actually saying is a little more difficult. I’m saying, when they’re asking me to answer a certain question, I’m saying, “I don’t think that’s the right question. I think we should be asking another question.” I’m not saying that because I’m afraid of saying what I believe. I’m saying that because I’m trying to be faithful to God, I’m trying to be faithful to the teaching and example of Jesus. So it’s my fidelity to my understanding of the Christian message that makes me say sometimes, “We’re asking the wrong question.”

I think Jesus was in this situation a lot. People would come to him and ask him a question, and it just wasn’t the right question. And he had a way of asking them a question or telling them a story that suddenly took them in a different direction. I think many of our questions that we’re asking today are just the wrong questions, and I think this is one of the great examples of Jesus. He doesn’t just answer the questions people are asking; he raises new ones. I think we’d be in a much better shape today if people who are faithful to Christ started saying, “What are the most important questions? What are the biggest threats and problems, and what does the message of Jesus and the life and example of Jesus, what does it say about those issues?”

Let me read one quotation from GENEROUS ORTHODOXY to you: “We must continually be aware that the old, old story may not be the true, true story.” Can you understand why some evangelicals are nervous when they hear that kind of language?

Yes, I certainly understand why they’re nervous, and to tell you the truth, these questions that I’m raising, that I’ve been grappling with for about 15, 16 years pretty intensely myself, they made me nervous, too. I’m very sympathetic. But I look back in history, and I think, you know, for a long time people who believed in Jesus, believed in the Bible, either tolerated or actively defended slavery. I grew up, you know, in the 1950s and ’60s, in an era when people who were very committed to the Bible, very committed to Jesus, were also very committed to segregation. I heard a lot of Christian people defend racism based on a Bible verse. So I think ethically, out of faithfulness to God and especially when we’re historically even marginally awake to history, we’ve got to realize that people in the name of the Christian faith have done some horrible things. We always have to be open to places where we’re wrong. And maybe this is one of the real problems, that if the public Christian voice is always telling everybody else to repent but it’s never applying that to itself, then in a certain way we’re violating Jesus’ teaching. We’re worried about the splinters in everybody else’s eye when we have boards in our own. That’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to say, “Look, we have some boards in our own. We have some things in our own vision that maybe need some attention.”

Are there truths related to the faith that we can know, that we can be certain about?

Well, first of all, when we talk about the word “faith” and the word “certainty,” we’ve got a whole lot of problems there. What do we mean by “certainty”? If I could substitute the word “confidence,” I’d say yes, I think there are things we can be confident about, and those are the things we have to really work with. This is one of the concerns that some people who are critical of my work have, and I understand their concern. Their concern is they feel you have a choice between certainty and a lack of confidence. Well, I think that there is a proper level of confidence. For example, the people who are sure that white supremacy was justifiable based on the Bible — they were certain about it. I don’t think they had many second thoughts about it. The Europeans who spread around the world and stole lands from the first nations, the native peoples of Africa, North America, South America, Asia — they had no shortage of confidence. They were certain that they were allowed to go and take everybody’s lands and, I mean, the results were horrific for hundreds of years.

So certainty can be dangerous. What we need is a proper confidence that’s always seeking the truth and that’s seeking to live in the way God wants us to live, but that also has the proper degree of self-critical and self-questioning passion. And that’s not a passion for being wishy-washy or, what was the word in the last election, to be a “flip-flopper.” It is a passion to say, “We might be wrong, and we are always going to stay humble enough that we’ll be willing to admit that.” I don’t see that as a lack of fidelity to the teaching of the Bible. I see that as trying to follow the teaching of the Bible. It has a lot of positive things to say about humility.

Are narrow, flawed, limited human beings able to ever fully grasp truth?

I believe G. K. Chesterton said something like this — that if we try to get all truth into our head, we will pare the truth down to fit into our head. The goal isn’t to try to fit it into our head. We’re limited. You can’t fit something infinite into your head. But the goal is, can we get our head into the truth? Another way to say it is I think truth can be apprehended; it can be touched. But can truth, especially truth about things like God — that can’t be contained. You could say it can be apprehended but not fully comprehended. And this, of course, is the deep tradition of the church. The church has always said that God is a mystery. The church has always said that our very best words about God fall short. So there is always the sense that the ultimate goal of worship is wonder and humility and awe. When we make it sound like we have all the bolts screwed down tight and all the nails hammered in and everything’s all boxed up and we’ve got it all figured, at that moment, I think we have stopped being faithful and we have in some ways created what one theologian calls a “graven ideology.” It’s an idol of our own conceptions.

A lot of critics are really frustrated that homosexuality is a question you’re not very definitive on. Why do you not want to go on the record on that?

That’s a great question, and we could talk for hours about this. I think, as I said before, when an issue is badly framed, we’re not wise to just rush in and try to answer it. And I think the issue of homosexuality is badly framed. One of my concerns about the framing of it is that I’m worried that the religious community is being manipulated by the political world and that the political community, in some ways, has decided this is a wedge issue, and we can use this issue to shave off voters from one party or another party. And so they’ve wanted the issue to be a political issue. I’m worried that the religious community has been manipulated by some of this political machination. I don’t mean that as a conspiracy theory, but I just mean let’s be realistic about how these things work. It seems to me it’s worked that way; that’s the first thing.

The second thing is that the issue of homosexuality is so complex, and as a pastor I have to sit across the table from people, from a young man who’s raised in a wonderful Christian family and says, “Look, you know, I’m 19 years old. I’ve never been attracted to women. I didn’t ask for this. I’ve been ashamed to tell anybody. You’re the first person I’ve ever told.” Well, when I have a conversation like that, or with a young woman who grew up — her father is a minister, and she lived with this deep self-hatred for many, many years. She considered suicide and all the rest. When you have conversations like that, you can’t just walk around making pronouncements like so many people in the media do. You realize these are real human beings we’re talking about. And you realize that the issues are not as simple as many people make them sound. Then add to that the biblical dimension of it and the way of interpreting the Bible that yields these very easy, black-and-white [answers], throw people in this plastic bin or in that plastic bin and now we got them sorted out, here are the good ones, here are the bad ones. You know, I just think that’s absurd. The Bible’s so much more complex then that. If people want to start picking out a verse from the Bible here and picking out a verse there, and picking out a verse, we’re going have stonings going on in the street. It’s a crazy way to interpret the Bible, in my opinion. Now that doesn’t mean that we just throw out the Bible, but we’ve got to learn ways to engage with the wisdom in the Bible that help us be more ethical and more humane and not less. So that would be, you know, one whole dimension of this.

In some ways homosexuality is the tip of the iceberg, and underneath, what’s not showing, is this huge issue that theologians would call anthropology. What is our view of humanity? For centuries and centuries in the Western church there has been an anthropology of dualism, that the body is like a machine and the soul is like a little ghost that lives in the machine. Soul and body are separated. But one of the things that’s going on in our world right now is a profound rethinking of that because we are learning, you know, through the study of mental illness, psychiatry, psychopharmacology, that body and soul are far more integrated than we thought in the past. That has implications on so many things. Let me just give one quick example. In the Bible you will not find the category of mental illness. There’s nothing in the Bible about schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, multiple personality disorder. You won’t find Asperger’s syndrome or autism in the Bible.

The thing that you will find in the Bible that’s closest to any of those things is demon possession. So if we say, “Well, the only way to be faithful to the Bible is not to give Lithium or Haldol or Prozac, or whatever, it’s only to do exorcism” — well, I mean, we would be brutalizing people. It would be ridiculous to treat people that way. I think that’s a bit of what we’re dealing with underneath the surface with homosexuality. We’re dealing with the fact that human beings are far more integrated body-soul units than we’ve realized in the past, and this is the deeper issue.

In the past, when the Christian faith grapples with major issues in our worldview like this, it takes centuries to deal with. So the idea that we have to have a solution and a definitive answer by yesterday on a complex issue is, to me, just unrealistic. It’s not going to happen that fast; we’ve got to have extended dialogue. I believe it’s possible to have Christians with different views on this issue behave charitably and work together. A lot of people say it’s impossible. I believe it’s possible.

Several of you who are part of the emergent conversation put out a letter to your critics addressing concerns raised about your view of Scripture. What is your view of Scripture?

The church from the very beginning has struggled with the issue of authority. In the early church you had apostles and false apostles duking it out; who’s right? And you have a lot of arguments in the documents of the New Testament where you realized there was conflict. Who has the legitimate right to speak authoritatively for the way of Jesus?

And then in the early centuries of the church you have an ongoing struggle between various leading cities, and eventually in the West Rome predominates, but in the East — you know, the Eastern Orthodox Church never is comfortable with that. Eventually by about 1000 you have an official rift, and then you have a rift between Catholics and Protestants. There have been these struggles — who has the authoritative message and the right to say the way things are and the way things will be for the Christian faith? For the last 500 years in the Protestant world, we have said the Bible tells us how things are and how things will be. The problem is that people interpret the Bible so differently. And so we end up with this, I think, naiveté that if we think the Bible tells us something without us doing any interpretation, we’re kind of, it’s like me sort of not realizing I actually do have a pair of glasses on, I do have an interpretive grid. I have a way of seeing.

The battle that’s going on right now is all of us believe — I don’t hear any of us saying, “Throw out the Bible,” you know, people have said that over the last couple of hundred years, and that doesn’t lead anywhere. If you throw out the Bible, all you have left is to be conformed to your culture, and you’re not going to have anything new to say than what everybody else is saying. I don’t see the great value in that; that seems to me a huge step down. None of us want to throw out the Bible. But what we do want to do is become more savvy and more aware of our interpretive grids that we bring to the Bible.

One good way to think about the Bible, for me, is to think of it as the scrapbook or the memorabilia, the essential documents that tell us the story of people who believed in one true, living, just, holy, loving, merciful God. It’s not like there are 25 traditions about it. There’s one, it’s the tradition that begins with Abraham, goes through Moses and David and comes to Jesus, and continues to us today. What those documents do is they give us, in my view, a kind of trajectory, a sense of development, a path of the way that God wants things to go. When you real all the details of the Bible, you see things go up and down and all the rest. But there seems to be a trajectory and a path. What that does for me is it helps me — let’s say the last of the New Testament documents ends about 100, somewhere in that range. Well, that sets this trajectory. And maybe I’m out here, but now I know if the trajectory’s going like this, I want to position myself here … and it helps me aim for a continuing trajectory so that we can live in our day in ways that are pleasing to God and are good for God’s dreams for the world.

Are you surprised at the extent to which you’ve really become a target and at the enthusiasm with which some people in the church have been criticizing and dissecting some of your writings?

I grew up in a church that would broadly be considered fundamentalist; I grew up in a sector of the church that was more in the world of fundamentalism. They’re wonderful people, and they love God, and they’d be wonderful people to have as your neighbors; they’re great people. I have great resources from my heritage in a very conservative sector of a conservative part of Christianity. I thank God for my heritage. One of the things I gained from my heritage is an understanding that there is a lot of vigorous debate, especially in the fundamentalist sectors, and the language gets pretty hot pretty fast sometimes. I have tried to not indulge in that kind of language myself. I don’t think that’s the best way to conduct dialogue. Sometimes the language is intended to shut down dialogue, and I think that’s not a good thing.

But overall, because I understand how that works, and I’ve seen a lot of it in my life, I’m more impressed by how charitably I’ve been treated. I think a lot of people could have been a lot rougher on me. I think deep down, for many of them, there’s a certain sense of hope. They’re saying, “We hope you don’t go too far, but we think maybe you’re doing something good to stretch the envelope.”

I’ll give you just an example. One very outspoken critic of mine said to me, “I don’t like what you’re writing. I don’t agree with you, but in a weird way I hope you succeed because my son will never, ever practice the kind of Christianity I practice, but he loves what you’re doing. And I think maybe a person like you is the only person who’s paving the way for a faith that my son can live, even though I want no part of it myself.” I think there’s a good bit of that going on, and I’m not the only one who’s doing that. There are people like Bishop N. T. Wright and Walter Brueggemann and so many important theologians. In many ways I’m kind of a translator of theologians into, you know, common, more accessible language. But so many people are paving the way for this, I think.

You don’t feel like you’ve become a target in some way?

Well, I certainly have become a target for some people. For example, it’s a little disturbing to see people writing reviews of my books on Amazon or whatever and it’s clear they’ve never read the book. There becomes a group of people who are just out to, you know, now I’m identified as a bad guy, so they’re trying to sort of join the cause and making me look bad or whatever else. Those things happen. There’s a bit of controversy, but you know, I’ve never really counted this up, but I bet there might be hundreds of positive e-mails and letters and comments I receive for every negative one. It’s just that some of the negative ones have been placed by well-known people.

Do you enjoy pushing the envelope?

Well, this is the irony. I’m kind of an introvert by nature. I’m sort of an artistic temperament by nature. I’m not a fighter. But I think I’ve always been a curious person. When I was a little kid I was fascinated, like a lot of little boys are, you know, with dinosaurs and with animals and wildlife. And I read everything I could. I’ve always had this thirst for knowledge. I think that’s maybe the thing that keeps me going. I really want to try to understand what’s going on. I have this curiosity. And when certain people say, “You can’t think that,” or “You can’t ask that,” or “You can’t explore that,” there’s part of me that says, “I don’t really have that option to just turn off my brain and turn off my curiosity.” I mean, if God gave me a brain, I don’t think it’s especially honoring to God to just sort of say, “In order to fit in this social setting and not get criticized, I better, you know, just inhibit it and put it in a box and put it on the shelf.”

How has all of this exploration and conversation affected your personal faith?

I came to a very strong Christian commitment in my teenage years. It was a combination of questioning and sort of spiritual experience that brought me to that. In my experiences, and I think for many other people, there is kind of a personal and very hard to explain, you know, deep — and maybe I could use the word “mystical,” probably the word “spiritual” is better — but an experiential side of faith. And then there’s a rational side, and sometimes one gets ahead of the other and sometimes one pulls the other back. I’ve lived with that dynamic tension, as I think a lot of people do.

In the early 1990s I hit what has been, so far, the biggest crisis in my faith. I’d been a college English teacher. I left teaching. I was working in pastoral ministry for about four or five years by that time. And so now I’m in the role of a pastor and I have to get up and preach every Sunday. But I started having some pretty deep questions. Now those questions, in some ways, came from the people who were attending my church. We started attracting a lot of people who were not lifelong churchgoers. And they would come and make an appointment and they’d say, “Boy, you know, I’ve been coming here for six months, and I never used to believe in God. Now I’m starting to believe in God, but I got these questions.” And they would give me their questions, and their questions were different than the questions I had and the questions all the books I read were about. Those questions really set me on a search. I would say that in 1994, ’95, ’96 I wasn’t sure, in fact I was quite sure that I was not going to stay in ministry. I just thought … “The tide of questions is rising faster then I can keep up with.” By about ’96, ’97 I started being able to, in some ways, disentangle my faith from certain systems of thought. And I found out that my faith actually would thrive better without being stuck in those systems of thought. And so I’m very hopeful now. I’m so glad now, but in ’96, ’95 — those were tough years. Maybe that’s why I’m sensitive to people who go through spiritual crisis. I’ve been through it a couple times myself.

What are some of the characteristics of an emerging church worship service, gathering, community, whatever you want to call it, that would indeed resonate with someone who is very much a product of today’s culture?

Well, my good friend Dr. Leonard Sweet, who’s been a huge inspiration to many of us, has a really nice way of summing it up. He uses a little acrostic around E-P-I-C: experiential, participatory, image-based, and communal.

Experiential meaning it’s not just a matter of coming and sitting in a pew and enduring 50 or 70 or whatever minutes of observing something happen. But it’s saying, “I want to experience God. I’m interested in coming into an experience here.” Participatory — I don’t want to just sit in my seat and watch other people do religious things up there. If there’s prayer being involved, I actually want to pray. If there’s singing involved, I want to participate. And it also involves getting our bodies involved so that here, for Protestants who’ve shied away increasingly from things like kneeling and things like receiving Communion and all the rest, there [is] renewed interest in spiritual practices that I participate in.

Image-based — we’ve been very word-and-concept based in the Protestant tradition for a long time, so that the centerpiece of the service is a long sermon. But to be image-based means there’s a huge increase in the valuing of the arts. So there might be a painting that is part of, actually, the message. “Let’s look at this painting and exegete the painting in a certain way, or appreciate the painting, or a sculpture, or interior design,” that sort of thing — great appreciation for the arts and things that relate to images and inspire the imagination.

And then communal — that we actually want to be connected with people. We don’t just want to come in and sit in long rows and just look at the front, and have as little contact with anybody else and as much contact with maybe the religious professional up front. But no, we want to actually be connected with the people and be part of the community. We come to believe that faith is actually, if I could say it this way, it’s a team sport. It’s not just a solo thing; it’s something we’re connected with other people in.

But in many of the worship experiences in this emerging church there is a strong individualistic element as well. Is there a paradox here, because people in some ways pick what works for them — if it works for you to paint up front, you can do that, or if it works for you to do this or that? You have people in some ways gathered together, but having a very individualistic, unique experience.

Yes. Well, life is so complex like that, isn’t it? There seems to be opposite things going on at the same time. And in one sense to have everybody sitting in rows, not moving, all looking forward, you could say that’s a highly communal experience. Everybody’s doing the same thing at the same time. But in a certain way, everybody’s individualism is inhibited, and they’re all rendered into this sort of nameless, amorphous mass. And in a way it does increase community when, for example, one of my favorite moments in my church, in our church service, is when I’m sitting there and other people are coming forward to receive Communion. I look at the people coming forward and I see tall people, and short people, and people of different races and economic backgrounds. I see people with Ph.D.s and G.E.D.s, and there’s something of the experience of seeing the people do things as individuals that helps me connect to them more as a community. So I think there are paradoxical things there. The fact is there is always a gravity in our culture toward commodifying and turning everything into a consumer, an individual consumer product. Will, you know, these churches involved in this emergent conversation, will they suddenly rise above that? Of course not; it’s pervasive. You know, it’s everywhere in our culture. It’s something we all struggle with.

Are we as individuals qualified to select what works for us within that setting? Are we the best judges always of what we get the most meaning from?

It’s a great question. It’s probably another one of those both-and questions. I think there are people who are gifted to be leaders and liturgists, they’re gifted in their skill just as a journalist develops skills and what are the good questions to ask, what are the issues that need to be addressed. People say, “Look, there are things we need to do when we get together,” and they have a guiding role in helping make sure those things happen.

I’ll give you an example. One of the things I really value in very traditional worship is the confession of sin. Now for some people that’s morbid, and they say it’s all about guilt. I don’t see it that way. I see the confession of sin as something we do as a community, as a constant reminder that we’re just all a bunch of losers, that none of us are all that great, none of us can – should — consider ourselves better then anybody else. There’s a kind of communal humbling in a confession of sin and a realization that we all need mercy from God and we should give mercy to each other.

Well, if a group of people say, “Oh we don’t like to think about sin, that’s negative, let’s just forget about it,” I think that’s a mistake, and we need gifted liturgists who will guide people in that, back into those things that, over time, they’ve proven themselves nourishing to the soul. Another really important author in this whole emergent conversation has been Dr. Robert E. Webber. A term that he has used is “ancient-future.” Ironically, as we move into the future, we find ourselves reaching back for more of these elements of our deep Christian tradition, and I see that as a very healthy thing.

One thing that’s really obvious in the emergent conversation is how much everybody hates labels. Everybody’s a postconservative or a postliberal, or a “post” this or “post” that. What is it about these labels that just doesn’t seem to be working anymore?

Great question. My friend Jim Wallis recently wrote a book called GOD’S POLITICS, and I love the subtitle:WHY THE RIGHT GETS IT WRONG AND THE LEFT DOESN’T GET IT. There’s this feeling in the political world and in the religious world that a lot of our polarities are now paralyzing us. So for example, if Left and Right politically are paralyzed in fighting each other, you know, we’ve got 300,000 or 400,000 people dead in Darfur in Sudan, and these people are fighting each other. We have to stop being paralyzed in our polarization, and we have to start working together to help some other people.

A lot of us feel that these categorizations are very effective to keep us fighting with each other, and we’d like to get beyond that and do something more productive. I was speaking in another city yesterday, and I made one statement and a young woman — I’m going to guess 23, 24 years old — came up to me afterward and she said, “That one sentence is what describes my spiritual life.” What I had said was more and more of us are feeling that if we have a version of the Christian faith that does not make us the kind of people that make this a better world, we really want no part of it. We actually believe that it’s right for us to have a faith that makes us the kind of people that help make this a better world. She said, “That’s me.”

I fear that what happens in our polarization is we stop saying, “Am I becoming a person who’s more Christlike? Am I becoming a person who’s more a part of God’s mission?” And we think, “Am I being a good conservative, or am I being a good liberal, or am I being a good Protestant or a good Catholic?” And, you know, that can end up really being a colossal adventure in missing the point.

How important has the Web, the Internet, and especially blogging been to this emergent conversation?

I’m 49, and for me, I live on the Internet. I mean, e-mail is my main mode of communication. But I know that for me, still, there is a certain kind of secondary sense to cyberspace. For me, television is still my native technology, and this is sort of a new technology. But we have to realize that for emerging generations, the Internet is their native technology, and so it really is transforming things.

One of the positive effects it’s had for the emergent conversation is that it’s global immediately. So there are people in Malaysia and all across Africa, Latin America, who suddenly can find out there are other people grappling with these issues, and there could be wonderful interchanges. It crosses denominational lines. It just has a wonderful way of helping people find each other that I think is very, very positive.

Blogging has been very, very important for this because it helps people express themselves. And a great thing about blogging is most bloggers have comment sections, you know, so there can be debate and dialogue. Sometimes it’s pretty combative and strident and pugilistic, and I don’t like all that kind of religious fighting language. But, on the other hand, it’s great that there’s space for people to passionately engage with issues they care about. We need that space, and cyberspace is providing a lot of it.

Can it also provide an endless conversation that’s just exhausting and never goes anywhere?

Well, this is one of the great dangers, and something I hope that bloggers themselves will pay attention to: that if you spend day after day, week after week blogging about what we ought to do for the poor and you never actually get out and do anything, you can have entered into a new kind of — what some people call the “paralysis of analysis.” Eventually probably what everybody ought to do, whether it’s a writer like me, we ought to say, “Let’s put the books down, and let’s actually go do something for somebody and not just talk about it.”

Are you still reluctant to call this a movement?

One of my hesitancies about calling it a movement is that I think it would be a shame for something to move forward until it has the right people in the gene pool, so to speak. I think we’ve got a lot of wonderful people in the gene pool. But I think there needs to be a lot more diversity. In the really big scheme of things, we’re at a moment now that is really unprecedented in Christian history. The majority of Christians in the world live in the global south. For the first time in Christian history, Africa, Latin America, and Asia, in many ways, are the center of Christian faith. The former colonies now are, in many ways, the center of gravity, not the former colonizers from Europe and North America. This is just a huge moment, and one of the things I’m especially interested in, and that I’m devoting a lot of my energy to in the next couple of years, is how can we find the young emerging leaders from the global south and the ones from the global north and have a global conversation about what the Christian faith should be? When that happens, that will be a great time to talk about a movement. It’s happening, but it takes time. Even with the Internet it takes time for these relationships to happen. It’s not just a matter of exchanging words. Something happens when people get together face to face and they share meals together, and I get to walk their streets and they get to walk my streets. And when we understand one another’s world, and we say, “This is God’s world and this is our world, and let’s try to figure out how we can be good stewards and caretakers and servants of God’s mission in this world, with north and south, east and west together,” that will be a great time to talk about a movement.

Certainly your critics have outlined a number of their concerns, but what are your worries or concerns? What do you see as the biggest challenges that face this conversation in the near future?

Whatever this thing is that’s developing — it’s not just about emergent; it’s a very, very broad thing. The Catholics are feeling it, mainline Protestants, evangelicals, charismatics — many, many sectors of the church are feeling it. And my biggest concern is that, if we were to say what is the very best thing that could happen, you know, let’s say that’s a 10 on what could happen, it would be relatively easy to get to a four or a five, but how can we really get up there to seize the opportunity of this moment? The moment involves so many things that have not done well for a long time. How do we integrate a real concern for evangelism and making authentic disciples of Jesus Christ? How do we integrate that with real concern for social justice and real concern for peace and reconciliation in our world? [That’s a] huge issue. How do we help Christians maintain an authentic, deeply rooted, Christ-centered Christian identity and engage in meaningful dialogue with members of other world religions and with people with no religion? How do we engage in dialogue? We don’t have a great history of that. We need that, and we need to practice that. Some people are more advanced at that than others, but sometimes the people who have had the most experience in engaging in dialogue do so by, in some ways, minimizing their own faith identity. So this is a new challenge: how do we maintain our identity and engage in fruitful dialogue? A major issue.

Then I think we’re faced with issues like HIV/AIDS in Africa, the floods of orphans and the flood of economic crises that’s going to happen in Africa just because of HIV/AIDS. We’re dealing with this sort of historic cultural struggle between what I would call a kind of medieval Islam and a very modern — in some ways still colonial — Christianity, and how can we engage in helping that become not a world-engulfing crisis? So many huge issues.

Another huge one is the loss of faith or the loss at least of religious practice in Europe. How can we help Europeans — and intellectual, blue-state Americans — to rediscover a faith that’s authentic and real and vital and that helps us move forward in the future? All of those are huge issues. It would be a good thing if we helped revitalize a lot of our churches, but to me that’s like a four or a five. But if we see this thing turn into something that has real implications for health and well-being in our world, that to me has a lot of the feel of God’s will being done on earth as it is in heaven, which is something all of us Christians pray for.