In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Brain Imaging

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, a development in medical technology that, like so many others, raises troubling ethical questions. It concerns the emerging science of brain imaging and its potential to reveal not only what is going on now but what a person might be likely to do in the future. Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

(From MINORITY REPORT): Who is the victim? I never heard of him, but I’m supposed to kill him in less than 36 hours.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: In the movie MINORITY REPORT, Tom Cruise’s character was convicted of a crime he was supposed to commit — in the future. It may be science fiction, but the idea of predicting future behavior may not be that far-fetched.

With increasing precision, scientists are able to peer into the brain, most commonly with magnetic resonance imaging. MRIs are used to scan the brain for disease. But fast new functional MRI machines can yield snapshots of human emotions and potential behaviors.

MRI TECHNICIAN: All right, John. The scanner’s going to calibrate for 20 seconds. You’re just going to hear a buzzing noise. Okay?

DE SAM LAZARO: At Emory University in Atlanta, Dr. Clinton Kilts recently conducted functional MRI scans on 16 executive M.B.A. students. The study’s volunteers were told to read about and react to a fictional character confronting various moral dilemmas in the workplace.

Dr. CLINTON KILTS (Emory University School of Medicine): There are specific areas of the brain that represent the repository of all your learned and aspirational content of self, and represent a key element of being able to decide when something is right or wrong.

DE SAM LAZARO: Dr. Kilts is a psychiatrist. His goal is more effective treatment for psychiatric disorders.

Dr. KILTS: We have a very poor understanding of the neural basis of sociopathies. And I think techniques like this offer us a considerable amount of insight into the biological basis and improved treatments.

DE SAM LAZARO: Brain imaging, using tools like this MRI machine, is the new state of the art in medical diagnostics. It goes well beyond genetic tests, which can predict the probability, even likelihood, of developing disease. Brain imaging can probe into the biology of behavior — and thoughts.

Valuable as these insights are to doctors, some ethicists fear they come perilously close to invading people’s zone of privacy.

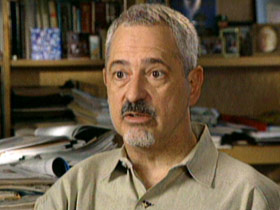

Dr. ARTHUR CAPLAN (Center for Bioethics, University of Pennsylvania): People are beginning to say, “What if I really did begin to understand personal identity better, who you are, better than you do?”

DE SAM LAZARO: Without intending it, many researchers are gaining such insights, with far-reaching potential beyond medicine, notably in forensics. For example, Dr. Daniel Langleben’s research could someday yield a lie detector that’s far more accurate than polygraph tests, which are rarely admitted as evidence in courts. Langleben’s interest actually was attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD.

Dr. DANIEL LANGLEBEN (University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine): Patients with ADHD, indeed, have some trouble producing, at certain circumstances, producing intentional lies.

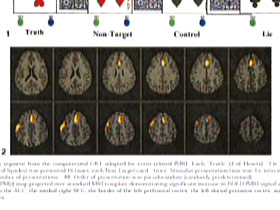

DE SAM LAZARO: So he set out to see what deception, or lying, looks like on an MRI scan.

Dr. LANGLEBEN: We take those images and superimpose them on those (points to brain scan) to be able to accurately locate areas of changed activity.

DE SAM LAZARO: Functional MRIs were conducted on 35 subjects in two studies at Langleben’s University of Pennsylvania lab.

Dr. LANGLEBEN: I was pleasantly surprised to see that there are parts of the brain that showed increased activity when the person is telling a lie. However, there was no part of the brain that showed increased activity when the person is telling the truth.

DE SAM LAZARO (to Dr. Langleben): So we are naturally inclined to tell the truth?

Dr. LANGLEBEN: Correct. In fact, when you think about it, this is expected because we know the truth and we don’t know the lie, so it should require additional effort.

DE SAM LAZARO: Dr. Langleben cautions his work is still in its infancy and may never result in a reliable lie detector test. But ethicist Arthur Caplan says it may not need to be accurate to be used, or perhaps misused.

Dr. CAPLAN: If somebody says, for example, today, “I am not a pedophile,” well, then I think you could show them stimuli and try to get measurements of their brain that might give you some information about whether that is true or not. I wouldn’t use it to diagnose the condition, but for some purposes right now — for job employment, or let’s say you are trying to screen people for national security reasons or to enter religious orders. Maybe you don’t care if it’s 100 percent accurate. You are just going to avoid people who might be problematic. That technology exists today.

DE SAM LAZARO: So far, brain imaging technology has taken only baby steps out of the lab and into the outside world.

Adam Koval works for one of the first for-profit neuromarketing companies in the world. It is studying how consumers think and respond to marketing messages. It’s information that could never be discerned from the focus groups most marketers use today.

ADAM KOVAL (BrightHouse Institute for Thought Sciences): There are a lot of inherent biases in focus groups, the need for someone to feel like they are presenting you with information that you want to hear. If you say, “Do you like this product?” They will say “Yes,” but they can’t articulate it on an analytic scale.

DE SAM LAZARO: Beyond commercial uses of brain imaging, there are also compelling social applications. Just as brain imaging can tailor effective marketing messages, it could also help create better antidrug campaigns, for example. The question Caplan says we’ll ask increasingly is, “At what cost to our privacy?”

Dr. CAPLAN: I think our ability to protect our confidentiality and our privacy will be put in peril by this technology. Not because we can’t legislate privacy, but those who have the goods will say you have to yield that privacy in order to get them. So you want this job? Yield this privacy.

DE SAM LAZARO: A couple decades from now, Caplan says neuro-imaging could revolutionize our whole concept of self. It could tell us that choices or behaviors we thought were of free will are actually predetermined, the result of our brain’s wiring.

Slowly, it seems, the line is blurring where the neurons end and free will begins.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, this is Fred De Sam Lazaro in Atlanta.