In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Altruism

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, the phenomenon known as altruism — generosity to others with no expectation of getting anything back. For many, giving is a religious requirement: the Christian Golden Rule — unselfish love; for Jews, the 613 “mitzvot” — good deeds to be done; for Muslims, it’s “zakat” — distributing some of your income to the poor and treating others as you would like to be treated. Others just do good whether they are religious or not. We have a Lucky Severson story today about people who are altruistic.

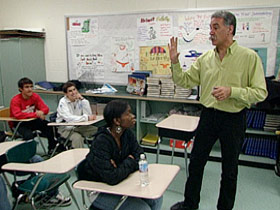

LUCKY SEVERSON: This is Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda, Maryland. The guest lecturer is Harold Mintz. He’s here to talk about a subject that is easy to define but not always easy to explain — why we sometimes do good things without expecting good things in return. It’s called altruism.

HAROLD MINTZ (Lecturing to Students at Walt Whitman High School): Five years ago last month, I gave my kidney to somebody. That in itself is not that unusual. That actually happens all the time, which is a good thing. What makes this story a little bit more unusual is that I gave my kidney to someone I didn’t know.

SEVERSON: His wife, Susan:

SUSAN MINTZ (Wife of Harold Mintz): Well, we decided we would take it a step at time. And when he said he’d have to, you know, go through a battery of tests, I went, “Okay, we are in. There’s no way he’s going to pass the psychological test.”

SEVERSON: University of California political science professor Kristen Renwick Monroe started out as a political economist, but she discovered that altruism undermines the assumption that people only act out of self-interest.

Dr. KRISTEN RENWICK MONROE (Professor, Political Science, University of California, Irvine): One of the problems I have with a lot of the research in this area, particularly because there are policy consequences, is that they enshrine a kind of sanctity to self-interest. And then they say this is, you know — greed is good; this is what we should be doing; it makes the world go ’round. And altruism is interesting because it doesn’t fit that pattern.

SEVERSON: Professor Monroe has researched acts of kindness and compassion and written two books on altruism. She believes people act altruistically because of how they view themselves, how they value others, and their religious teachings. Doing good for others is a core principle of all the world’s major religions — Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism. Loving your neighbor as yourself is an act of altruism. Harold Mintz says he doesn’t think religion was the reason he donated his kidney. He thinks it had to do with how helpless he felt when his dad died.

Mr. MINTZ (Lecturing to Students at Walt Whitman High School): Fifteen years ago, I came home from school one day, and my dad said to me over the dinner table, “I went to the doctor today. He says I’m sick.” He had cancer. From the day he came home and told us he was sick to the day he passed was five weeks. I guess the whole frustration of having nothing that I could do to help save my father, and yet there’s so many people that are dying when you know exactly what to do to save them.

SEVERSON: When Harold Mintz said he was giving a kidney to a person he didn’t know, some thought it was more a selfish act than an act of altruism.

(To Mr. Mintz): When your friends and acquaintances found out what you were doing, did some of them think you were either crazy, a, or b, irresponsible?

Mr. MINTZ: All the above. I had friends who think it’s wonderful. I’ve had friends who were angry at me for making the decision to do that, who said, “You shouldn’t do that. How can you do that to your family?”

SEVERSON: But the family, including their daughter Hayley, gave him their blessing.

HAYLEY MINTZ: My dad has only one kidney. My mom has two.

SEVERSON: Sometimes altruism is not the act of one individual, but of many. Consider the farming village of Le Chambon in southern France during World War II. Over a four-year period, 5,000 Protestant Christians sheltered about the same number of Jews from the Nazis and almost certain death. Hilde and Jean Hillebrand could never forget, nor completely understand, the selfless generosity of the people of Le Chambon.

HILDE HILLEBRAND (From Documentary, WEAPONS OF THE SPIRIT) (Speaking in French): They really did something. They risked their lives.

JEAN HILLEBRAND (From Documentary, WEAPONS OF THE SPIRIT) (Speaking in French): They hid us in their farms. They knew the police were near.

Ms. HILLEBRAND: They said we were cousins, relatives.

Mr. HILLEBRAND: They put themselves in danger, taking every risk.

SEVERSON: This was altruism on a grand scale, and Professor Monroe says it happened in part because the people of Le Chambon identified with the persecuted Jews.

Dr. MONROE: The Chambons were Protestant Huguenots. They had been persecuted. They had a memory of that. And one of the theories that people talk about is that you understand what it’s like to be in another person’s place. You have a kind of empathic involvement with another human being that makes you feel what it is like to be them.

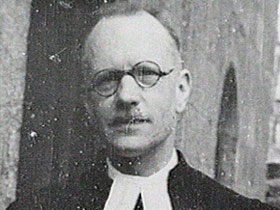

SEVERSON: Le Chambon’s spiritual leader was Pastor André Trocmé, a pacifist whose resistance stemmed from biblical teachings. In this documentary, WEAPONS OF THE SPIRIT, Pastor Trocmé’s daughter reads from a sermon he gave to the congregation.

PASTOR TROCMÉ’S DAUGHTER (Reading from Sermon): The duty of Christians is to resist whenever our adversaries will demand of us obedience contrary to the orders of the gospel. We will do so without fear, but also without pride and without hate.

Dr. MONROE: These were people who felt they were a certain kind of human being, and Madame Trocmé said, “These decisions are about you. They’re not about other people. If you believe — do you believe that the Jews are your brothers? If so, then you have to act on that.” And that’s what I was told over and over by rescuers.

SEVERSON (To Prof. Monroe): This was the whole village?

Dr. MONROE: The whole village. The whole village. It was very much a kind of contagion of goodness.

SEVERSON: Out of the ashes of 9/11, there was another contagion of goodness.

COURTNEY COWART: The immediate response when people from all over the world just left their normal lives, got in cars, got on planes, and came to New York to say, “How can I help?”

SEVERSON: Courtney Cowart was working in one of the offices of Trinity Church, just a few blocks from the [World] Trade [Center] towers. She describes herself as one of those gray ghosts coming up Fifth Avenue.

Ms. COWART: I remember my brain racing, trying to calculate, “How do I protect myself?” And then realizing there’s nothing — there’s nothing you can do. It’s a moment that’s almost impossible to put into words, but it was a feeling of, “Take me.”

SEVERSON (To Ms. Cowart): A transforming moment?

Ms. COWART: (Nods Her Head Yes).

SEVERSON: She became one of the leaders of the St. Paul Ministry, of what she calls “a community of love” — thousands of volunteers of every race, political persuasion, religion or no religion, who rose above the rubble to personify the basic goodness of humanity.

Ms. COWART: One of my favorite conversations was with a crane operator named Joe Bradley. He was absolutely devastated, sitting on the curb with his head in his hands, and he talks about this teenager from the Salvation Army with pink hair and her belly button showing coming in the middle of the night and giving him cold water and literally washing his feet. And, you know, he said, “I never identified with those kind of people before. But that night she became my hero.”

UNIDENTIFIED POLICE OFFICER: The outpouring of love and support was so — was something I thought I would never experience. I saw humility and compassion in its truest form.

Ms. COWART: The way we were — people were running in to sacrifice themselves for others. It was like a huge revelation of how precious we are to each other, even total strangers. To me that is where God was in this.

SEVERSON: If you do an altruistic act, do you feel good?

Dr. MONROE: I think usually people do, but not always. A lot of times people thought that it was just a kind of normal thing to do.

SEVERSON: For Harold Mintz, giving the kidney has given him a cause — to persuade kids about to get their driver’s license to sign the back saying they want to be an organ donor.

Mr. MINTZ: If everybody signed their driver’s license right now, nobody would die waiting for a kidney, plain and simple. If you hear about a good deed, it kind of reminds you, “Oh yeah, I guess I can do that. I don’t have to turn my back or have to, you know, do something.” I don’t look at myself as an altruist or whatever the title you want to put on it. I look at it as having taken advantage of an opportunity that was in front of me at the time.

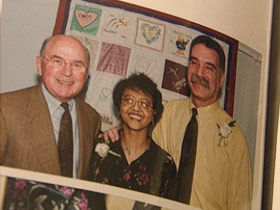

SEVERSON: But most important, his kidney saved a life of Gennett Belay, a young mother of two who had been waiting and praying for a new kidney for 11 years.

Ms. MINTZ: She had, like, 40 operations. She had had different bouts of different kinds of cancers.

SEVERSON: And now two families have become one extended family.

Mr. MINTZ: What’s not fair to say is I didn’t benefit. I benefit immensely from it. My head feels much better. My heart feels much better because what I did worked.

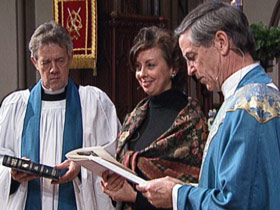

UNIDENTIFIED MINISTER (Trinity Church): I commission you, Courtney Cowart, as relief development coordinator to New Orleans.

SEVERSON: For Courtney Cowart, the transformation continues. Because of her good works for the survivors during the dramatic year following 9/11, she’s been sent to direct the disaster response for the Episcopal Diocese of New Orleans.

Ms. COWART: It was the most extraordinary year of my life. I have hugely positive memories. And it’s part of why I am so extraordinarily excited about the opportunity of going to Louisiana, because I know what’s in store.

SEVERSON: For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Lucky Severson in New York.