In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Between Science and Religion

by Chris Herlinger

Are science and religion compatible?

At a recent public forum at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, the answer from a panel of scientists and scholars was a nuanced yes.

Kenneth Miller, a biologist at Brown University and a practicing Roman Catholic who calls himself a religious scientist, said science and religion are intertwined and can never be separated. “All of human experience and knowledge are one,” he told the audience at the museum-sponsored event.

But if there was general agreement about the connection between science and faith, panel members also suggested there are ways the two can — and perhaps should — stand apart.

Nancey Murphy, a professor of Christian philosophy at the evangelical Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California, spoke of her experiences as a Catholic who later embraced a strain of charismatic Protestantism. While supporting the interrelationships between science and religion, she also said she believes the scientific worldview — which rational, liberal Protestantism accepts — does not allow for miracles.

That, she said, is one noticeable divide between religious conservatives and liberals, and she, for one, cannot deny the existence and importance of miracles.

Varadaraja V. Raman, a Hindu and an emeritus professor of physics and humanities at Rochester Institute of Technology, called religion and science the loftiest examples of humanity’s aspirations and strivings, but he, too, emphasized key differences: science is the effort of finite minds to grasp infinite complexities, religion the effort to grasp the foundation of those infinite complexities.

Both disciplines have limitations, Raman said. Religion can’t tell us about the substance of material conditions, while science can’t supply ethical or moral answers.

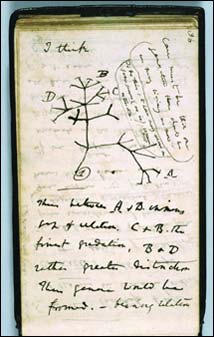

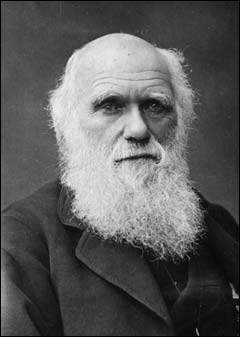

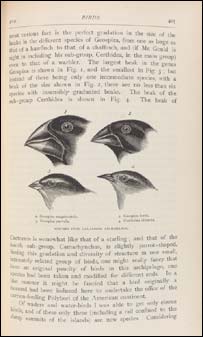

It was no accident that the forum on science and faith was held at the American Museum of Natural History. The stately building overlooking Central Park is currently the site for “Darwin,” the most extensive exhibition on Charles Darwin ever mounted, according to the museum. It features original manuscripts, letters, specimens, memorabilia, and two live tortoises from the Galapagos Islands, a key site in the travels that led the British naturalist and author of THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES to his conclusions about evolution and natural selection.

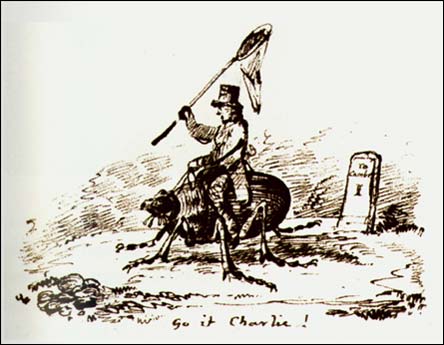

The exhibition methodically chronicles Darwin’s life and scientific contributions, but it doesn’t shy away from the arguments that greeted his work — 19th-century cartoons, for example, lampooning Darwin’s thinking by portraying monkeys in human settings. The exhibition also places the current debate about evolution and intelligent design in historical context and suggests that controversies over Darwin’s thought are almost cyclical events, to be expected every few decades.

Unlike past eras, however, when the religious-scientific divide might have been sharpest, with religious figures on one side and scientists wholly on the other, the exhibition also features videotaped testimonies from well-known contemporary biologists and paleontologists who strike a conciliatory tone, suggesting, as one says, that there is “nothing inherently contradictory about being a scientist and having religious faith.” (Darwin himself entered the University of Cambridge prepared to become a clergyman.)

Francis Collins, director of the Human Genome Project, says in one of the exhibition’s taped interviews that “the tools of science are the way to understand the natural world, and one needs to be rigorous about that.”

But, Collins adds, “I’m also a believer in a personal God. I find the scientific worldview and the spiritual worldview to be entirely complementary. And I find it quite wonderful to be able to have both of those worldviews existing in my life on any given day, because each illuminates the other.”

In the taped interviews, the exhibition acknowledges that there is an understandable attraction to current notions of intelligent design.

Eugenie Scott, executive director of the National Center for Science Education, says intelligent design holds “that there are some things in nature that are just so incredibly complex that they could not be the result of natural cause.”

But Collins suggests this approach essentially “puts God in the gaps, and it says if there’s some part of science that you can’t understand, that must be where God is. Historically, that hasn’t gone well.”

“If we’ve put him in a box — if we said, ‘Okay, God has to be in this particular part of nature and science explains that,’ then we have potentially done great harm to people’s faith,” says Collins.

Not surprisingly, the scientists who were part of the museum’s recent panel discussion still passionately defend Darwin and evolution. Miller, who earlier this year told comedian Stephen Colbert on cable television’s Comedy Central that God “is a guy who was so clever that he set in process a motion that gave rise to everything on this planet — you, and me, and maybe even Bill O’Reilly” — also says in one of the exhibition videos that science would be lost without Darwin’s theories.

“Without evolution, the things that we do in the laboratory and in the field, the experiments we carry out and the interpretations we make from those experiments are not connected with each other,” says Miller. “You might say that without evolution to tie it together, biology is little more than stamp collecting.”

Like Miller, Robert Pollack is also a self-described religious scientist. He is a Columbia University professor of biological sciences who directs Columbia’s Center for the Study of Science and Religion and teaches a course at New York’s Union Theological Seminary on “DNA, Evolution, and the Soul.” Humanity may try to run, but ultimately it cannot hide from Darwin’s theories and natural design, Pollack said at the recent science and faith forum.

Natural design, explained Pollack, is “the absence of purpose, the impossibility of perfection, and the centrality of individual mortality we find in Darwin’s fully confirmed model of natural selection. Natural design is the way things are.”

“All that remains is to acknowledge it and act accordingly, and that is actually not such a small thing. There is nothing in this natural design that prevents us from choosing to act in ways that ameliorate its punitive consequences,” said Pollack. “Rather, natural design gives us all our common humanity, and with it our natural and absolute dependence upon the goodness of others for the entirety of our mortal lives. But we cannot begin to know how to choose to act in good and helpful ways, let alone to take proper actions, until we acknowledge the reality of natural design.”

“Darwin” will be on exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History until August 20, 2006. It will then travel to the Museum of Science in Boston, the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, and the Natural History Museum in London.

Chris Herlinger, a New York-based freelance journalist, writes for RELIGION NEWS SERVICE, ECUMENICAL NEWS INTERNATIONAL, THE CHRISTIAN CENTURY, and NATIONAL CATHOLIC REPORTER. He last wrote for RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY on movies and religion.