In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Inner City Churches on the Move

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: The migration of Americans to the suburbs, a phenomenon of the mid-twentieth century, wasn’t just about families. It included their institutions as well — churches and synagogues. And when they left, those congregations were often criticized for abandoning their urban communities.

Now, a growing black middle class and the lack of available land in cities are luring some African-American congregations to suburbia as well, depriving their old neighborhoods of the ministries that had served them. Reporter Kelly Hudson tells the story of Sharon Baptist Church in Philadelphia.

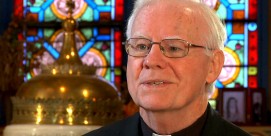

Reverend KEITH REED (Pastor, Sharon Baptist Church): We get locked into doing something one way so long that we have a hard time moving and transitioning to the move of God.

KELLY HUDSON: Four years ago, Sharon Baptist Church moved from its inner-city home in Philadelphia to this new sanctuary near the middle-class suburb of Bala Cynwyd.

Rev. REED: We could no longer grow, we could no longer be effective as we were before — we became that large — so as a result of it, we came to the conclusion that maybe God is trying to push us out of our nest, out of our comfort zone, so that we can become even broader and more impactful.

HUDSON: Sharon Baptist is one of many increasingly affluent black churches that have recently moved from their inner-city homes. While many applaud the success of these churches, there is also concern among some people that this suburbanization is leaving a void in the neediest neighborhoods, like this one.

For nearly 40 years Sharon’s home had been in this poor community in West Philadelphia, where it seemed to be making a difference.

JAMAHAL BOYD (Member, Sharon Baptist Church): The neighborhood was a troubled neighborhood. You could go two blocks in any direction and run into all types of chaos and trouble that was there. The church was a protected area.

Rev. REED: We ran drug dealers off the corners because of the presence, the activity that was going on because of the church.

HUDSON: Under Reed’s leadership the congregation grew tenfold, from 240 in 1982 to 2,500 members by 1999. Sharon was now reaching beyond its immediate community to serve middle-class blacks commuting from surrounding suburbs.

JOHN YOUNGE (Member, Sharon Baptist Church): We were turning people away. You have to understand. First, we put people in the basement with no monitor — they were just listening over the loudspeaker, and finally we got a TV down there. Then we got a building next to our administration building, put a closed-circuit TV over there, and we still started to turn people away because they couldn’t get in.

HUDSON: Sharon, now located close to a major highway, increasingly serves a membership from as far away as Delaware and Maryland. Some believe this expansion comes at the expense of Sharon’s least fortunate members.

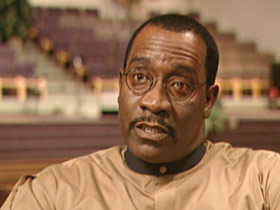

Dr. OMAR MCROBERTS (Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Chicago): Historically, black religious institutions have had to play the role of the house builder, the psychologist, the bank — all kinds of roles. And so in neighborhoods where black churches have been present, of course, for a church to leave could present a crisis for that neighborhood.

Rev. REED: The thing that is so strange to me is, why do we look at the church abandoning their communities when they grow? It’s not. They’re broadening their effectiveness wherever they go. So they not only have impact where they were, but they also have impact where God has taken them to be.

HUDSON: When Sharon departed from the old neighborhood, it took away its food and clothing ministry, youth ministry, men’s ministry, and drug and alcohol rehabilitation ministry.

Church leaders say they’ve compensated in other ways. Its hip-hop-style Christian café draws teenagers and young adults from the inner city. The addiction ministry works with other churches in their old neighborhood. On this night, two members deliver clothing to a halfway house. Sharon has started a community-based credit union and says it plans to build low-income housing. It also buses members from its old neighborhood to Sunday services and other events.

TYLER HARLEY (Director of Business, Sharon Baptist Church): We tried to stay in the West Philadelphia area. The biggest challenge was, where do you find eight acres in the city of Philadelphia?

HUDSON: To help make up for its absence in West Philadelphia, Sharon made a commitment to lease its former building to another church. But with a much smaller congregation of roughly 100 members, it cannot possibly replace Sharon’s presence.

MARY LILLY (Neighborhood Resident): Sharon had a great impact on the neighborhood. They won a lot of souls. Like when I came home from work, it was late at night. Some guys over there were always going in and out. They always had a kind word to say. They know how to touch the heart. That goes a long way.

HUDSON: Meanwhile, Sharon has been enormously successful in nurturing its new church community, which now exceeds 7,000 members.

Dr. MCROBERTS: Is the community the geographic neighborhood surrounding the church, or is the community the set of people who have attended your church for a long time and who are now also your source of revenue, and who are now leaving to the suburbs? So ultimately, the question is about how religious institutions understand community and understand their mission.

HUDSON: The leaders of Sharon Baptist insist they have not abandoned the people of their old neighborhood. But their move does highlight the potential costs of success for inner-city churches and the communities they serve.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Kelly Hudson.