Harold Dean Trulear: A Spirit of Revivial

I watched her run circles around the gym, seemingly oblivious to the history in which her mother involved her. Her African braids flowed in the musty air lingering from countless middle school physical education classes. Her arms stretched wide as if she understood what it meant to soar — soar as the man that five hundred people stood in queue to support on a dismal day in a black working class suburb of Philadelphia.

I watched her run circles around the gym, seemingly oblivious to the history in which her mother involved her. Her African braids flowed in the musty air lingering from countless middle school physical education classes. Her arms stretched wide as if she understood what it meant to soar — soar as the man that five hundred people stood in queue to support on a dismal day in a black working class suburb of Philadelphia.

Only the weather was dismal. The mood was jubilant, fervent, literally transcendent. Black people stood in line without complaint and with hope. “Victory is mine” shouted a local pastor upon her exit from the dusky gym. I saw poll workers in business casual and poll workers with backward baseball caps. Seniors on canes and boyz in the hood stood together, and no one nervously clutched her purse. It was history.

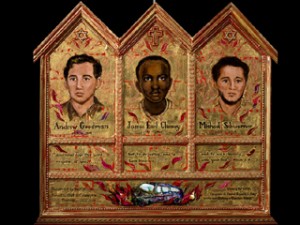

I have never been more proud to be a black man. Because I felt part of something — a community that did not care that I am a card-carrying Republican, because they knew how I would vote. I would vote for the men and women who gave their lives that this day might come to pass. So when I voted for Barack Obama, I dug deep with no regrets. It was a vote for him — and Liuzzo, Schwerner, Goodman, Reeb, and Cheney. Evers and Till being dead yet speaketh.

If those names are less familiar to you than the names of weak presidents such as Buchanan, Grant, and Pierce, then you get my point. The platform of the presidency has elevated men (not a typo) unworthy of the office. Whether or not Obama will become as those weak leaders, or whether history will proclaim him to rank with Lincoln and Roosevelt will be determined by time.

But the hope engendered by his candidacy transcends the power of his message. African Americans stood in long lines, misty rain, and in full view of racist antagonists to say “this is one of us,” despite the fact that his father was an African and his mother was white. The accident of history identifying any person of color as a Negro enables blacks with a long history of dealing with racism to identify with a man who does not share all of their history, but by color and commitment lays claim to their predicament.

So I joined the party of the people of the predicament — the girl with the braids, the seniors on canes, the families voting together, the cars driving by honking their support, and the revivalist fervor of a people who felt that this time they had a voice. It was the voice of those who stood — no, marched for the rights of those who now stood for hours to vote. The voice cried, “My feet are tired but my soul is rested.” How dare anyone complain about the blood rushing to feet standing in the voting line when compared to the blood shed for a democracy celebrated across the planet. Blood flowed and feet blistered that the orator — he of the preacher’s rhythmic call and response (“yes, we can”) — would be the next president of the United States. Change and hope kissed on an autumn night celebrating a union that felt religious, transcendent, almost otherworldly in a world of pragmatic politics specializing in the art of the possible.

Transcendent — that’s spiritual stuff. A spirit of American and even African-American revivalism grew in the days approaching the election. Many congregations and religious bodies organized prayer vigils on both sides of the partisan sea. As in 2004, one group emerged convinced that its prayers were answered. Those who believed that they would never see an African-American president in their lifetime attributed Barack Obama’s victory to divine intervention. Organizations prayed for candidates committed to issues as varying as assisting the poor, sanctity of one man-one woman marriage, and even the counting of votes — prayers lifted from the lips of Protestants, the pens of Catholic bishops, and the wisdom of Jewish rabbis.

While praying for a campaign does not constitute new behavior, the more public display of faith on the Democratic side had not been seen since the civil rights movement (when there was a somewhat different Democratic Party). Indeed, African-American communities recalled images of the religious fervor of the civil rights movement in the grass-root similarities between the marches of the sixties and the Obama campaign organization of 2007-2008. Even Obama’s acceptance speech both borrowed from (“we as a people will get there”) and referenced the work of Martin Luther King, as did several pundits and newscasts. One TV broadcast even juxtaposed King’s “I Have a Dream” speech with Obama’s election night address.

The little girl running circles through the gym soared with an energy reminding me of the highest aspirations of the human spirit. Her presence in an intergenerational gathering of voters who did not complain about the two- and three-hour waits at the polls reminded me of the lines of marchers who put their lives on the line so that we might stand in this new line.

No one was tired. There was a borrowed strength from feet that had marched and knees that had prayed. It was the spirit of revival.

–Harold Dean Trulear is associate professor of applied theology at Howard University School of Divinity.