Charles Mathewes: The Meaning of Elections

I spent most of this morning working for the Obama campaign here in my hometown of Charlottesville. I’ve been away from home since Thursday at a conference. First thing in the morning my family got up, got dressed, and we all went off to vote. I took my daughter and baby son into the booth with me, and my daughter got to help select our choices and then confirm the ballot. My wife, who is Canadian, had never been to an American polling site before; she found it quite moving–all the people, excited outside, the matronly poll workers, even the middle-aged men seeming to move with the understated, regal deliberation of grandmothers.

After I cast my ballot, I began, somewhat covertly, to cry. I squeezed my daughter’s shoulder hard enough with love and hope to make her scold me. Then it was off with her to school, and the rest of the day has been a whirl of data-entry, driving voters to the polls, getting balloons for this evening’s party, and generally participating in the highly oxygenated anxiety that is a party’s local headquarters on the day of the election. I found it deeply exciting, but also humbling, even awe-inspiring, in a way for which I wasn’t fully prepared.

Since then I’ve been thinking a lot about the curious, and not entirely unhappy, coincidence of meanings in the word “election.” On the one hand, citizens elect representatives; on the other, prevalent in the faiths stemming from Abraham, God elects humans–first a people to be God’s messengers and representatives to the world, and then, through them (but not canceling out their election), and in Christ, all of humanity to be God’s children. An election is something someone does, to be sure; but it is also something that happens to people, as well. There is a remarkable coordination of theological and political significance in “election,” and it is worth noting–if only to resist the powerful idolatrous temptations it presents to us.

Those temptations have such power, not least because they identify quite profound resonances between politics and theology in general. After all, so much of politics, as it exists today in this impatient, petulant, risibly sin-riddled world, is waiting. We wait at rope lines for candidates to pass; we wait for election returns to arrive late at night, faces pale in the sterile glow of TV screens; we wait while a canvasser reads us his talking points on the phone, or urges us to support her candidate on our doorstep.

Less obviously, we wait for our friends and family and neighbors and co-workers and new acquaintances to enumerate, in what often seems to us inexplicably, narcissistically meticulous detail, why their chosen candidate or cause is obviously the only right one, wondering all the while where to begin in disputing their whole way of seeing the world. Sometimes we must even wait for our own minds to make up their opinions on issues we feel we need to have a view on now, if not yesterday. And always we wait to see–with fear and trembling, if we are pious and wise–whether the political causes we supported ultimately turn out the way we hoped they would turn out. (Usually this means waiting to find out how, precisely, we shall be disappointed.) Much of public life is spent enduring interminable time, when time itself drones on.

And then, sometimes suddenly, a change comes. Everything happens, all at once: deliberation ends, the ballots are cast, the votes counted, decisions made, the New Thing emerges. The old order–which seemed so solid, so firm, so unchanging–is swept away by the unprecedented. Politics is a disconcerting concatenation of kairos and ordinary time, with jarring shifts from one to the other, a kind of wild oscillation between “now” and “not yet,” the world as we know it and the Kingdom coming.

Lord knows there has been enough messianism and enough demonization in this campaign. People on both sides have participated in both of these temptations; I certainly have. It’s obviously a temptation to be avoided.

And yet.

There is, after all, more than a superficial connection between the two realities. People do treat their faith like a simulacrum for politics all the time–assuming that religious differences easily classify all of us in this world, separating us into clear categories. And we all know what it means to treat politics with religious fervor, especially here in the United States. Since the beginning, American politics has been saturated with not just superficial pieties, but with profound theological currents as well. We’ve always been involved with a more or less self-conscious quarrel with God over whose election was more important–God’s election of the people Israel, or our election of our leaders, and behind them, of ourselves.

Beyond these rivalries between America and America’s God, however, there seems to me a still deeper analogy to which we should attend. It lies in the ambiguities of that term “election.”

To be elected is to be marked out in a special way, to be sure. But election is not an unambiguously happy fate. It certainly hasn’t been one for the people Israel. It wasn’t for Jesus Christ. And Christian theology says it should not be understood as one for the graciously elected. The fundamental obligation of God’s elect is to be present before and available to God, to say, in ancient Hebrew, hinneni: “Here I am.” Hinneni was Abraham’s answer to God’s call to sacrifice Isaac, Samuel’s reply to God’s call to become a prophet, the reply of the people Israel in Sinai to God’s election of them as a people. (It was also what Adam and Eve did not say to God in the garden, and what Cain did not say to God after killing Abel.) To say “here I am” is a deceptively simple thing to say; but it leads those who offer it, as a kind of sacrifice to God, to terrible places. It leads, as the risen Jesus says to Peter in the Gospel of John, to death: “When you are an old man, you will stretch out your hands and another will gird you and take you where you do not want to go.” “When Christ calls a man,” the twentieth-century martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer said, “he bids him come and die.”

Election to the presidency, too, is hardly an unambiguous blessing. Just look at presidents’ “before” and “after” pictures to see what I mean. George W. Bush looked like he was still uncomfortable in a suit in 2000; now his suits look more at ease than his face, and his once full dark head of hair has become thinner, and unambiguously grey. When Eleanor Roosevelt told Harry Truman that her husband had died, he said, “Eleanor, is there anything I can do for you?” To which Eleanor wisely replied, “Harry, is there anything we can do for you?” No doctor would recommend the job of president to people who cared about their health; no insurance agent would willingly insure a president against death. To be elected president seems, in part, to mean that one is set apart for a certain kind of public suffering. What looks like the polished marble of divine promise turns out, after a few years in the office, to have been the sandstone of simple humanity, forced to wrestle with super-human challenges. Would that we were all a bit more like Eleanor Roosevelt.

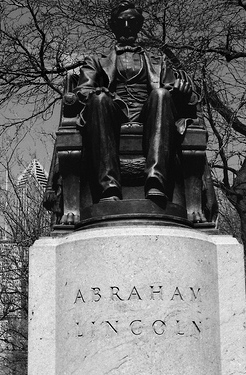

Wise presidents seem to know this from the beginning, or at least seem prepared to learn it. Abraham Lincoln famously said, “I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me.” Perhaps, as with God’s election of people, all a president can do is say, “Here I am.” Perhaps all presidents are Abraham.

But in this, as in all things, presidents are simply representatives of the people, the incarnation of the popular will. They suffer for all of us; they take upon themselves what is rightfully ours. If so, our belief that we elect presidents is an illusion; we are simply picking one of us to endure, in a particularly vivid way, what is the rightful desert of all of us. We simply pick someone to be the first to absorb what history throws our way. Our election still rests on events beyond our control. Our election is, once again, consequent to our being elected. Whether by history or God, in this respect, does not matter; what matters is that we receive more than we decide; we are acted upon more than acting, and no one, ironically, more so than the winning candidate, the “leader,” whichever he is, who will now know what it is to be taken by another and led through four years in a way he did not wish to go.

I told you at the beginning of this essay that I was away from home this past weekend. I was in Chicago at the annual conference of the American Academy of Religion. Everyone was talking about the election, of course. But few among my fellow conference-goers seemed to realize the fearful symmetry to which we were witnesses. My conference was in the Chicago Hilton and Towers, fronting Grant Park–the same hotel that the 1968 Democratic National Convention was held in, and the same park that saw the famous Chicago “police riot.” On Friday night, I was in the Presidential Suite on the 24th floor of the hotel, facing out on Grant Park. It was in that suite that the newly nominated Democratic presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey sat, tears streaming down his face. The tears were not from sadness or despair, but simply from the tear gas rising from the streets outside; but I like to think that Humphrey’s tears were also a premonition of what that convention’s catastrophe foretold for the Democratic Party: forty years in the wilderness.

Last Friday night, looking out the same windows that that tear gas came in, I saw the tents coming up in Grant Park for the Obama victory party. Tonight, God willing, I say, Obama will hold his victory celebration in Grant Park, with the old Hilton looming overhead, a brooding mausoleum of the ironies of history.

History has not ended. It has ironies in store for all of us, and certainly for a President Obama, or a President McCain. Whoever you supported for the presidency, whichever man wins it, whatever your religious beliefs, or irreligious beliefs, or nonreligious beliefs: Say a prayer, or think a good thought, give all best wishes for the man we elect tonight to be our next Abraham, and watch him as he walks out on his stage, out into the open, to say–still innocent of the blades and cudgels already hurtling at him from the future–“Here I am.” In the years to come, may he be faithful to his words.

–Charles Mathewes teaches theology and ethics at the University of Virginia. His most recent books are A THEOLOGY OF PUBLIC LIFE and PROPHESIES OF GODLESSNESS.