Security and Privacy

MARY ALICE WILLIAMS: Privacy is at the heart of our special report. A year ago, we had the technology to hack into people’s most private personal information, track their whereabouts, invade their space. Doing it was widely considered unacceptable. Then what technology had made possible, terrorism made inevitable.

Surveillance is increasingly pervasive. So where is the acceptable line between greater protection of the public and invasion of individual privacy? Lucky Severson reports from Ybor City in Tampa, Florida.

LUCKY SEVERSON: That camera was just moving — it was following us?

Detective BILL TODD (Tampa Police Department): Yes, it’s looking right at us.

SEVERSON: Detective Bill Todd is in charge of the high-tech camera system keeping an eye on visitors in an area of Tampa called Ybor City.

(to Detective Todd): So inside the control room right now, it’s going ding, ding, ding as it tries to match our faces?

Detective TODD: As it’s trying to capture our faces.

SEVERSON: By day, Ybor City is so quiet, it’s difficult to imagine what it’s like at night. Especially Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights. That’s when Ybor City really opens up — as many as 125 thousand fun-seekers each night, and a huge headache for Tampa police. That’s when the special cameras go to work.

Detective TODD: That is the capture alarm, saying the system found a face. It’s alerting the monitor that the system found a face.

SEVERSON: It’s called face-recognition technology — software connected to Ybor City’s 36 cameras. An officer operating the system chooses a section of the crowd, scans the faces, then compares them to those of local, national, and international criminals stored in the database.

Detective TODD: If the system were to say it believes it found someone, it would then ring an alarm to alert the officer. That’s no different than what we’ve been doing for hundreds of years with wanted posters. “Hey, that’s the guy on this wanted poster.”

SEVERSON: It’s the first surveillance system of its kind in the country, but there are more on the way. And there may be a price to pay.

Professor NEIL QUINN (Director of Ethics & Technology, Santa Clara University): We are as citizens, whether we think so or not, relinquishing a certain amount of what we previously deemed as private actions. We are now considerably more visible than we ever were previously.

SEVERSON: Face-recognition cameras first gained national attention when they were used to try to catch criminals and pickpockets at the 2001 Tampa Super Bowl — with no success. Critics called it Snooper Bowl. The Ybor City system, recently upgraded, has been operating for over a year.

(to Detective Todd): Have you caught bad guys?

Detective TODD: We haven’t caught any yet, but I think that it’s going to prove to be an effective tool.

SEVERSON: The cameras, he says, may work as a deterrent.

Detective TODD: A guy knowing that he’s a wanted felon may think twice before he comes down here.

MIKE PHENEGER (Retired Army Special Intelligence Officer): It’s an invasion of privacy. Basically, every time you walk down the street, when that system’s on, you’re being subjected to a high-tech lineup.

SEVERSON: Mike Pheneger is a card-carrying Republican, an avowed conservative, a retired army special intelligence officer, and a spokesman for the ACLU.

Mr. PHENEGER: The police are actually putting you through a lineup unbeknownst to you with no probable cause to believe that you’re guilty of anything.

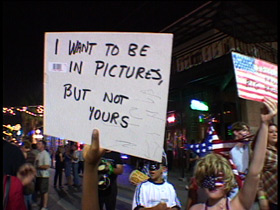

SEVERSON: When Tampa first approved the system there was a small protest, but after September 11, opposition seemed to disappear.

Prof. QUINN: The events of 9-11 may have, you might say, broken the back of the rugged individualist mentality that exists in the country.

MELANIE SANDLER: If there’s technology that can help you find the person that’s perpetrated a crime, I think that’s fabulous.

KEITH EVANS: If they want to look at my life, I feel sorry for them. They’ll be very bored.

SEVERSON: But most people we spoke with didn’t know the cameras were there, and several weren’t at all happy to find out.

MARK LARUSSA: It just feels like, you know, you almost feel like you’re in a zoo.

BRENTON AHYE: Slowly but surely, all of our rights are being taken away after September 11.

SEVERSON: If it is ethically acceptable to visually eavesdrop on people who have nothing to fear to catch those who do, when does the intrusion go too far? Take the woman here in the Tampa area who is hiding from her husband, she says, because he beat her and molested her two daughters. She has a morbid, if unrealistic fear that her husband is going to trick the police and use the cameras to track her down.

Unidentified Woman: In the past he’s gone around with pictures to the police and said I kidnapped the kids.

SEVERSON: This woman, who was afraid to be identified, is afraid to go near Ybor City.

Unidentified Woman: He comes and he finds me. I get beat up and I get put in the hospital and the police realize then that they’ve made a mistake.

SEVERSON: She says she’s an example, perhaps an extreme example, of how the technology can be abused.

Unidentified Woman: The police have always been good to me once they found out who was telling the truth. But they don’t find out who was telling the truth until after I’m in the hospital.

Detective TODD: The software, even if it were to capture her image, unless she’s in our database it doesn’t retain that image. It discards it.

SEVERSON: We may not be aware of it, but most of us are captured on video every day, almost everywhere — in shopping malls, supermarkets, banks, ATM machines, casinos, tollways.

Critics say police tend to zoom in on minorities. Some say that amounts to “FACIAL profiling.”

Prof. QUINN: The constant tension between the rights of the many and the rights of the few comes into play in issues like this — where society in general deems that we need to look at a group of individuals or some particular individuals more cautiously than we ever did in the past.

SEVERSON: The technology in Tampa is donated by Visionics. We asked for an interview with the president of Visionics, but we’re told that he would be too busy unless we agreed not to interview anyone from the ACLU for our story.

(to Mr. Pheneger): My impression is that Visionics is not very pleased with the ACLU.

Mr. PHENEGER: Well, probably not, but we’re not awfully pleased with Visionics.

SEVERSON: The ACLU recently issued a report saying the Tampa surveillance system simply doesn’t work very well.

(to Detective Todd): If you haven’t caught anybody, why are you so high on the program?

Detective TODD: Well, when we run tests on the program, it works. I mean, this is a work in progress.

SEVERSON: Although people complain about the cameras at Ybor City, that doesn’t seem to be the case when they’re confronted with yet another version of face-recognition cameras at Florida’s Clearwater International Airport.

SCOTT MCCALLUM (Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office): As a matter of fact, the general flying public has been very much in favor of what we have here.

SEVERSON: Scott McCallum is with the Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office.

Mr. MCCALLUM: What we’re doing here is we’re subjecting passengers to the normal screening process.

SEVERSON: So far, the system here has not caught any criminals or terrorists. But still, several airports in the U.S. have installed or plan to install similar technology.

And in Washington, D.C., a new $7 million surveillance system, capable of using face-recognition technology eventually, but not now, partly out of concern for civil liberties. D.C. Police Chief Charles Ramsey.

CHARLES RAMSEY (D.C. Police Chief): People are trying to make it sound sinister. It’s not sinister. It’s a useful law enforcement tool that will help us maintain the safety and security of all the residents and visitors here in the district.

SEVERSON: The technology is advancing at mind-numbing speed. Even now, face scanners are replacing passwords — fingerprints are substituting for credit cards. There are laser cards that store your health records from the day you’re born — cell phones that will reveal where you are — maybe eventually a national identification card.

Prof. QUINN: When you put those all together, they form a mosaic of information about individuals which is indeed scary.

SEVERSON: As technology rockets ahead and another September 11 haunts us, the line separating our fears and our individual freedoms is bound to become more and more difficult to draw. For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Lucky Severson in Ybor City.