Jew v. Jew

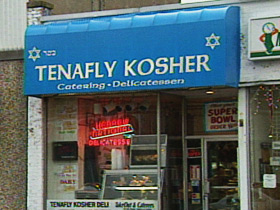

SAMUEL FREEDMAN: Tenafly, New Jersey, is a suburb of 16,000 people, nearly half of them Jewish, just across the Hudson River from New York City. They are mostly affluent professionals who were drawn by the town’s public schools, nature preserves, and ethnic mix. But when a group of Orthodox Jewish newcomers put up a symbolic boundary called an eruv, Tenafly became one of the latest battlegrounds in an ongoing civil war in the American Jewish community.

WENDY KLEIN (Tenafly resident): I am concerned that a message not be sent that this town is only appropriate for people of a certain religion.

JONATHAN SINGER (Tenafly resident): I believe in Tenafly that there must be some fear of strangers or people that are different.

CHAIM BOOK (Tenafly resident): I have a right just like any other citizen in a town of my choosing.

FREEDMAN: The larger debate is about the nature of Jewish life in America. The Orthodox often view the non-Orthodox as overly assimilated; the non- Orthodox tend to view the Orthodox [as] rigid and separatist. And, as the Orthodox leave close-knit urban neighborhoods for the suburbs, where less-observant Jews have long resided, a collision ensues.

STEVE BAYME (American Jewish Committee): The survey data on Orthodox Jews is remarkable. Fifty one, 52% feel the Orthodox are narrow-minded, feel that they are dismissive of non-Orthodox Jews, contemptuous of non-Orthodox Judaism.

FREEDMAN: Chaim Book and his family are part of the recent influx of Orthodox Jews to Tenafly. Two summers ago, without the town’s permission, this group of about 15 families erected an eruv around much of Tenafly. Almost invisible, the eruv was created by arranging for rubber strips to be attached to existing telephone poles and power lines. By symbolically extending the boundaries of a home to the entire enclosure, the eruv allows Orthodox Jews to engage in some activities normally forbidden on the Sabbath.

Mr. BOOK: The eruv is necessary and important for us because it serves a rather mundane purpose. It allows us to push a stroller to synagogue on the Sabbath, it allows us to carry items in the street, it allows a family to attend services together, and visit friends together.

FREEDMAN: But Tenafly’s Borough Council — in a unanimous decision — ordered the eruv to be taken down late last year. Now, the Orthodox community has sued and the case is in federal court. The legal issue is whether a town must accommodate this religious practice.

Ms. KLEIN: It’s troubling to me that a particular religious group would be asking the government to get involved to erect the eruv, which has a religious purpose. It sets a dangerous precedent that the next time another group comes along that the town finds that it also has to grant that accommodation or be accused of discrimination.

Mr. BOOK: What special accommodation is there in allowing black weather-stripping to [be] put up on a telephone pole, when the utilities have given permission to use the telephone pole and the group has given its own funds to pay for it.

WALTER LESNEVICH (borough attorney, Tenafly): Our council looked at our town, our position, our make up, and decided it was not a good thing for the town.

FREEDMAN: But the legal issue is not the most divisive one.

Ms. KLEIN: One of the things that has bothered me and has bothered other people in town is that the eruv people have acted as if the desire or lack of desire for the eruv to be erected was immaterial. It was felt that the eruv proponents were not acting as good members of the community. …

MURRAY MELTZER: I think that anyone who has spoken out against the eruv has been viewed as being anti-Semitic and in some way bigoted. And I find that a divisive atmosphere rather than an accepting atmosphere.

FREEDMAN: These fears are only exacerbated by the fact that Tenafly’s residents have watched the Jewish populations of nearby towns like Englewood and Teaneck become predominantly Orthodox. Such families, which use religious schools, have [a] less[er] stake in public education, and downtown businesses increasingly cater to an Orthodox clientele.

Mr. SINGER: There have been various comments on how the eruv would bring a greater influx of Orthodox to Tenafly, and by having an eruv and by having more Orthodox, it would affect the stores, there would be maybe more stores that wouldn’t be open on Saturday. It would change the tone of the town, and the fact that the Orthodox wouldn’t send their kids to public schools so that it would harm the public schools, and I just think that those sort of statements seem very discriminatory.

Mr. BOOK: My wife and I very easily could have purchased a home and moved into a neighborhood that was perceived as an Orthodox neighborhood, but we are the type of people that feel that we don’t want to live only with people exactly like us and would feel comfortable in a more diverse community, and the reason we moved to this community is because it is a diverse community.

Mr. BAYME: The question that the Orthodox Jews should confront and must confront is the larger issue, not of whether their specific demands or specific requests regarding an eruv or synagogue or zoning ordinance, the real question is the nature of relations between the Jewish people.

FREEDMAN: Ultimately, a court will decide the legality of the eruv. What it can’t possibly resolve is the conflict wracking the Jewish community. Tenafly is only the latest staging ground for this continuing battle between two ways of Jewish life, one celebrating the melting pot, the other devoted to religious tradition.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Samuel Freedman.