Who Really Killed Jesus?

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: For Western Christians, Lent begins Wednesday — Ash Wednesday. Wednesday is also the day the much-publicized movie, THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST, opens in theaters across the country. Months of controversy about it have raised the old question, “Who really killed Jesus?” For many, perhaps most Christians, that debate is history, but for Jews, as Kim Lawton reports, it still arouses deep fears of persecution.

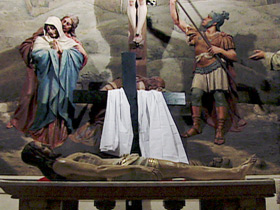

KIM LAWTON: It’s the teaching at the core of Christian belief and practice: Jesus suffered, was crucified and buried, but three days later he rose again. For Christians, the cross is an enduring symbol of grace, salvation, and love. But for many non-Christians — and Jews in particular — the cross has long symbolized violence and persecution.

Two thousand years after Jesus’ death, Mel Gibson’s controversial movie, THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST, has set off a wave of new conversations about who was responsible for Jesus’ death — and why it matters today.

Professor MARY BOYS (Union Theological Seminary, New York): In my business, I would call it a teachable moment. Many people are thinking about the meaning of the death of Jesus, probably in ways they haven’t thought before.

LAWTON: The conversation troubles many Jews, given the long history of Christians persecuting Jews as “Christ-killers.”

Professor Michael Berenbaum, formerly of the U.S. Holocaust Museum, is now with the University of Judaism in Los Angeles. He organized a public forum last week where an interfaith panel discussed the crucifixion. More than 450 people showed up.

Professor MICHAEL BERENBAUM (University of Judaism, Los Angeles): It’s a very complex, very long relationship. And Jews have usually been on the losing end of that relationship.

LAWTON: The crucifixion is described in the first four books of the New Testament, the Gospels. They are called the “Passion narratives” — passion coming from the Latin word for suffering. The Gospels have differing emphases and offer different details.

In piecing together the story, modern scholars also factor in the historical, cultural, and literary context of the Gospels. Many say the role of the Roman occupiers has too often been under-emphasized.

Prof. BOYS: Crucifixion was one of the modes of capital punishment in the Roman Empire. And, in this case, the death penalty, the crucifixion, was used only against marginal people or people who seemed to threaten the order of the state, which apparently Jesus did.

Prof. BERENBAUM: Crucifixion was never a punishment that Jews used as a part of their capital punishment. The rabbis and the Pharisees of that generation could not engage in capital punishment. We didn’t have the political power, even if we had the will.

LAWTON: But the Gospel accounts, to varying degrees, do describe a Jewish role in Jesus’ arrest, trial, and crucifixion — a role that has been re-enacted for centuries in Passion plays on stage and in films.

From film THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST: If we let him go on in this way, everyone will believe in him. The Roman authorities will take action and destroy our temple and our nation.

LAWTON: In the Gospel accounts, which are read in churches every Holy Week, an assembly of Jewish leaders charges Jesus with blasphemy. The Jewish high priests are portrayed as pushing the reluctant Roman governor, Pontius Pilate, to crucify Jesus, while a mob of Jews yells in favor of the crucifixion. For the Jewish community, the story raises sensitive, often painful questions. Are the Gospel Passion stories anti-Semitic? To what extent were Jews involved in the crucifixion?

Professor Shawn Landres, who is Jewish, teaches a class about Christianity to students at the University of Judaism. He says Jews need to remember that the Gospel writers themselves were Jewish and used strong language to convince their divided Jewish community that Jesus was indeed the prophesied Messiah.

Professor SHAWN LANDRES: What do I teach the students about the crucifixion? I teach them that there were Jewish leaders, political leaders, for whom Jesus’ teachings were heretical at best, and politically subversive at worst, and who felt that it would be better for him to be removed from the scene. That doesn’t mean the Jews as a people killed Jesus.

LAWTON: But there’s a complicated history. Perhaps the most provocative account comes in the Gospel of Matthew, when Pilate hesitates in crucifying Jesus. Matthew 27:25 says: “All the people answered, let his blood be on us and on our children.”

Over the course of 1,700 years, Church leaders and individual Christians have assigned a so-called “blood-guilt” blame to the Jews, accusing them of deicide — killing God.

Professor Kathryn J.S. Smith heads the biblical studies department at the evangelical Azusa Pacific University in California.

Professor KATHRYN J.S. SMITH (Biblical Studies Department, Azusa Pacific University, California): Those words taken into a new time and place indeed function in an anti-Semitic way, although I am convinced that the Gospel writers and the communities that produced these did not understand it in that way.

Prof. BERENBAUM: One of the traditional anchors of anti-Semitism has been the accusation that Jews are Christ-killers. If we can murder God, murder the son of God, then there is no limit to the evil and iniquity, to the perfidiousness, to use the word that was used in Good Friday liturgy within the Roman Catholic Church — there is no limit to the perfidiousness of the Jews.

LAWTON: Especially during the Easter season, when the Passion story was recounted and re-enacted, the accusation of Christ-killer was used to justify violence against Jews.

Prof. BERENBAUM: With persecutions, with pogroms, with slaughters, with martyrdom, with forced conversions, with expulsion, and ultimately with the Holocaust.

LAWTON: The Roman Catholic Church did not officially repudiate the Christ-killer notion until the 1960s during the Second Vatican Council. Earlier this month, the U.S. Catholic bishops released a new set of documents reaffirming that Jews bear no collective responsibility.

Bishop STEPHEN BLAIRE (Diocese of Stockton): I think it’s very clear in the teaching of the Church that all of us, by our sins, are the ones primarily responsible for the Passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

LAWTON: The evangelical American Tract Society takes a similar view in two new brochures, timed for the release of THE PASSION. They ask, “Who crucified Jesus?”

MARK BROWN (American Tract Society): The answer is, God did it. Ultimately, in the Old Testament, in Isaiah 53, it goes to a verse that says he was smitten and afflicted for our sake. And basically that God laid upon him the iniquity of us all.

LAWTON: Today Christians across the spectrum emphasize the doctrine that it was God’s will that Jesus died to take away the sins of the world. So, because of sin, all of humanity bears responsibility.

That may be a satisfying theological answer, but Professor Smith says it’s also one that can too quickly minimize atrocities against Jews done in the name of Christianity.

Prof. SMITH: There’s not a real grappling with, “This is our tradition. We are heirs of this tradition. What are we going to do with it?”

LAWTON: Much of the interpretation of the Passion story depends on what an individual brings to it. Professor Landres says Christians need to be more aware of the memories of persecution the Passion story evokes among Jews — as well as the fears that persecution could be revived. But he says Jews, too, need to deepen their own understanding.

Prof. LANDRES: I have yet to see a true acknowledgment from some members of the Jewish communal leadership that Christians just don’t read the story the same way Jews do.

LAWTON: Christians and Jews alike hope the new discussion about the crucifixion is an opportunity for dialogue, not more division. They agree the implications of Jesus’ death are vitally important, which is why, 2,000 years later, we’re still talking about it.

I’m Kim Lawton reporting.