Sex Selection in India

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: A special report now from India on the religious and ethical issue of aborting female fetuses. In India, sex selection by sonogram is officially illegal, but widely practiced. And there is no Hindu or legal prohibition on abortion. Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: This group home operated by a Hindu organization in New Delhi offers a safe haven from the city streets, where these children were abandoned. The sex ratio here — 37 girls, two boys — says a great deal about how girls are viewed in India.

DR. NINA PURI (International Planned Parenthood): Almost from creation to cremation, women are discriminated against.

DE SAM LAZARO: The root of the problem is ancient and economic. Male children are favored since they carry the family name and frequently get the family inheritance. Girls are viewed as liabilities, who will cost their parents a dowry when they marry and move into their husband’s homes in the Indian tradition.

DR. PURI: People feel that bringing up a daughter is like watering a plant in someone else’s house, because here they’re going to educate her, nurture her, spend money on her; ultimately she’s going to [be] married and going to somebody else, so what’s the worth of that?

DE SAM LAZARO: Years of campaigns and laws have failed to eradicate India’s dowry tradition, which cuts across all religions. The result is a history of female infanticide, and in recent years, abortion. Dr. Sharada Jain, a Delhi gynecologist, says about five million pregnancies were terminated last year, after parents found out they were expecting a female child.

DR. SHARADA JAIN (Gynecologist): Five million is a big number. And we activists feel it is only the tip of the iceberg. You interview anybody in my clinic. If she has had a girl child before, you can know it for sure that she has had a sex determination [test] somewhere else, and now it is a male child. That’s why she is carrying through with the pregnancy. As simple as that.

DE SAM LAZARO (to Dr. Jain): Do you see patients who have two girls in a row?

DR. JAIN: Yes, but the percentage is very small. I would say 10 percent.

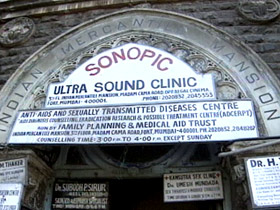

DE SAM LAZARO: Ironically, ultrasonography, one of the most beneficial diagnostic tools used to monitor fetal health, is widely misused in sex determination, leading to abortion. Ultrasound clinics are available is many places that barely have electricity.

The town of Palwal, about an hour and a half north of Delhi, has about 40,000 residents — small by India’s standards. Yet it has no fewer than 24 ultrasound machines. Not coincidentally, the population of Haryana, the province, has one of the most lopsided gender ratios: 830 females for every 1,000 males.

Normally, scientists say the sex ratio is about even, with slightly more females than males. This means that in India, nearly one in five female fetuses is aborted in parts of India — nearly one in 10 nationally.

This woman, a mother of three girls and pregnant again, is desperate for a son.

DR. SUDHIR SUBHANI (Radiologist): She was complaining about abdominal pain, so that is why we have done the scan.

Radiologist Sudhir Subhani said the cause of this patient’s pain became quickly evident: a twin pregnancy.

DE SAM LAZARO (to Dr. Subhani): Is it good news for her or bad?

DR. SUBHANI: It’s good news and bad news. She’s expecting one boy and one girl.

DE SAM LAZARO: You couldn’t tell her that?

DR. SUBHANI: No. She wanted to know, but I just told her that she had twins.

DE SAM LAZARO: Dr. Subhani told us, but at least by law, could not reveal the sex to the mother. In fact, in 1994 the Indian government outlawed sonograms for sex determination. Problem is, in a country where abortion is legal and widespread, the law has been difficult to implement. One thing it has done is raised the price of sex determination [tests].

DR. PRAKASH KAKODKAR (Gynecologist): Because the procedure is illegal and once you tell that to the patient, the patient doesn’t have any argument at all. If it was a legal procedure, then the patient would be able to bargain with you for such a procedure.

DE SAM LAZARO: Bombay gynecologist Grakash Kakodkar admits he’s a participant in a widely corrupt system. In principle, Kakodkar supports sex determination and abortions only when there’s a history of hereditary disease among males in a family.

DR. KAKODKAR: From the point of just sex determination, to terminate a female pregnancy, I am not in favor of it.

DE SAM LAZARO (to Dr. Kakodkar): But do you do it occasionally when requested to?

DR. KAKODKAR: Ya… ya… I do. I cannot deny that. Although whatever people say that they don’t do it, I still feel the majority of obstetricians are still doing it.

DE SAM LAZARO: Do you face any legal sanction for doing that?

DR. KAKODKAR: No, that’s what I said, there is no legal sanction because there is nothing on paper.

DE SAM LAZARO: Kakodkar says he does take into account the patient’s personal situation. Frequently, they’re under social and economic pressure, especially if they already have a female child or two. At the same time, he admits, business is so lucrative for the doctor, it quickly overcomes any ethical reservations.

DR. KAKODKAR: Initially, you feel a little bad, you know, for having terminated an un-indicated pregnancy, but subsequently I feel one loses that; it doesn’t bite your conscience that much. Let me be absolutely frank.

DE SAM LAZARO: You are being quite frank, in fact, much more than I expected.

DR. KAKODKAR: I’m saying it very, very frankly.

DE SAM LAZARO: And, terminations are the chief source of your income?

DR. KAKODKAR: Very much.

DE SAM LAZARO: Much more than delivering babies?

DR. KAKODKAR: Very much, very much. And if you don’t do it, somebody else will, because the patient is hell bent on having it done.

DR. JAIN: The doctors feel the government works so slow that nobody can touch them and that’s why the fear complex is not there. If one or two are caught and the media publicizes it, something can be done, [but] I don’t think there is political will.

DE SAM LAZARO: There does appear to be judicial will. Early in May, India’s Supreme Court ordered the government to step up its enforcement of the anti-sex determination law—something that even Dr. Kakodkar supports. So long as it’s properly implemented, he says.

DR. KAKODKAR: If it is done uniformly—everybody’s not going to do it—then it is a different story. So unless the government really puts its foot down and decides to act really tough with people who are doing this—I [am] doing this—I don’t think there is any way to curb the procedure.

DE SAM LAZARO: Kakodkar says doctors should be required to register all abortions done in the second trimester, when the sex of a fetus becomes readily discernable, and cite a reason why the termination was requested. That could dissuade many from engaging in sex determination procedures. Or it could simply raise the price for them even higher.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro, in Mumbai, India.